Packers have invested $1 billion this century, thanks in large part to 2003 Lambeau renovation

GREEN BAY – The Green Bay Packers invested more than $1 billion in Brown County in this century.

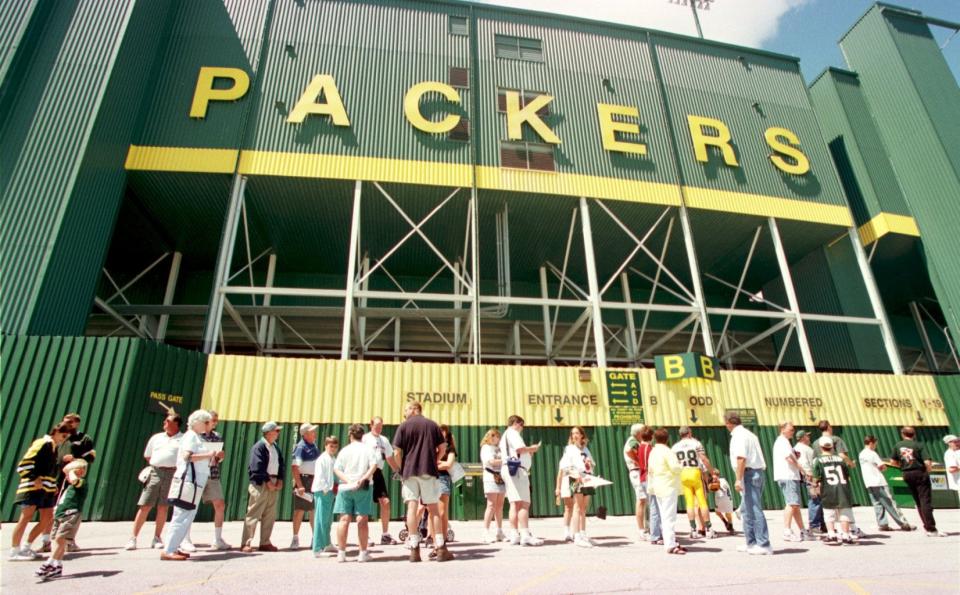

In 2000, the NFL's most iconic stadium was an oval bowl with metal benches, some small offices and even smaller Pro Shop, and the whole surrounded by corrugated-metal walls. It was open 10 times a year. Today, the bowl and the benches remain, but everything else is different on what has grown to be a large campus open to the public year-round.

The franchise was in financial trouble as the last century wrapped up. Then-President and CEO Bob Harlan tackled the problem head-on, asking Brown County residents to approve a half-cent sales tax to pay for a total renovation of Lambeau Field. The controversial proposal divided the community, with some saying it could be shot down because the Packers no doubt had a Plan B. Harlan said there was no doubt about it, there was no Plan B. In the end, the tax was approved (it was ended 15 years later) and a new Lambeau Field rose on the hill overlooking Green Bay.

The renovated stadium was officially rededicated at the start of the 2003 season.

"I think Bob (Harlan) and others kind of laid it out," said Packers President and CEO Mark Murphy. "If they hadn’t made that big investment 20 years ago, we would have been near the bottom of the league in terms of revenue. It would have been harder for us to compete. It had the impact, I think, that was probably beyond what they had hoped."

Fancier stadiums have since been built in Los Angeles and Las Vegas, but Lambeau remains a jewel in the NFL crown, both for its physical presence and its place in NFL tradition and history.

"I don’t think people have a realization as to how small Green Bay is compared to any other spot in professional sports. We are pretty minute when it comes to the L.A.s and the Dallases and the New York teams as far as the market," said Craig Black of De Pere, a Packers fan who grew up next door to Lambeau Field. "This takes second place to nobody."

While direct investment in Lambeau Field itself is just short of $1 billion, the organization has exceeded that mark across the entire Packers campus, which includes the practice fields east of the stadium, Titletown to the west and parking lots to the south. The Packers also have a warehouse and distribution center on Ashland Avenue that are new since 2003.

A study by consulting firm AECOM determined that the Packers and Lambeau contributed $281 million in total economic impact to the Green Bay economy in 2009. Accounting only for inflation, that would be $400 million in 2023 dollars. Add to that a more than 10% increase in Lambeau Field seating, the development of the Titletown district and renovation of the Atrium to make its businesses more successful, and total annual economic impact would be more than $500 million. Total economic impact of individual games was estimated at $15 million in recent years, although the amount now may be in the range of $18 million.

"There are great stadiums in New York and Chicago, but the (economic) impact is really minimal," Murphy said. "Whereas a $15 million impact for each home game is huge in Green Bay. And you add in the fact it's now year-round, and the addition of Titletown, it really has a huge impact on the community."

Harlan's foresight lets local revenue keep up with national income

It started with the Harlan-led renovation of Lambeau Field completed in 2003. That $295 million project was funded by a half-cent Brown County-only sales tax. The next $600 million or so was done without public financing, which probably would be impossible to get now.

"It's all been generated because of changes to the stadium," said Murphy, under whose 16-year leadership construction has been nearly continuous.

The explosive rise in NFL media income, which is shared equally by all 32 teams, made it possible to field a competitive football team year after year while simultaneously investing money in facilities and staff. Media revenue continues to be the lifeblood of the NFL, but increases in local income for the Packers were immediately noticeable after the renovation and have kept pace with national increases over the 20 years (the COVID-19 impact notwithstanding).

"TV money will always save us, but when you look at your list of things that help, your stadium is probably No. 2," said Harlan during a recent interview in the atrium he built. Harlan retired in 2007, when he reached the mandatory retirement age of 70.

Local revenue was $60.8 million in 2002. It jumped to $79.2 million in 2003 and $89 million the year after that. It has continued to increase, hitting $236 million in 2022-23. Local revenue is important because much of that does not have to be shared with other teams.

National income was $92. 6 million in 2002, $99.9 million the next year and $374.3 million by 2022-23.

More: Green Bay Packers report record revenue of $610 million ahead of shareholders meeting on Monday

More: Shareholders meeting: Packers recall a year of accomplishments, even if they missed the playoffs

Local income was 39.5% of all income in 2002, 44.4% in 2003 and 40% in 2021-22. It slipped to 38.6% last year, which the Packers attribute to having one less home date last season because of the game in London in October.

Harlan said they promised legislators and Brown County voters that saving Lambeau and having it open every day would accomplish four things:

"We could stabilize the financial future of the Packers.

"We could put a competitive team on the football field every year.

"We could guarantee that Green Bay would remain a viable part of the NFL for decades to come.

"We could bring visitors to Green Bay and Brown County literally from around the world."

"As we look back 20 years later, that's exactly what this stadium had done," Harlan said.

Rob Davis, who was a long-snapper for the Packers from 1997-2007 and now is director of organizational development & diversity, equity and inclusion, said that because the Packers have no one owner who takes money out of the organization, they have made the most of re-investment.

"This organization puts (money) back into the organization, back into the facilities," he said. "It's been great to see the growth and where it will continue to grow. Over the years ... all of the expansion that has taken place has only added to the aura of the Green Bay Packers, the standard of excellence."

Davis said that to players, the 2003 renovation was less about a better physical plant than to maintain Lambeau's atmosphere.

"Even the other locker rooms around the NFL weren’t drastically nicer than what we had here," he said. "We as players, I don’t know if it was as much about the stadium as the experience. I think it still holds its character from yesteryears."

In terms of player facilities, such as the locker rooms, Green Bay was on par with most other teams, but first-class player facilities were, and are, key to attracting talent.

"That was a big thing here, to never let the football facilities get outdated," Davis said. "When you are coming from other ballclubs, you’d be like, 'OK, the Packers got them beat.'"

Harlan and his executives were sensitive to history and character, which was why he didn't want to move the stadium.

"I love the intimacy's and tradition of this stadium. You can't build a stadium like this today," he said. "You've got Wrigley Field, Fenway Park and us. We tell people who come here, this is where Vince Lombardi teams practiced and played. That to me was huge. Every team doesn't have tradition. We do. We need to preserve it, sell it, use it, be proud of it."

In the 1990s, Packers were in familiar position: financial distress

Looking today at healthy Packers' finances, it's hard to remember that for most of its existence the team lived from hand to mouth, and at the end of the 1990s, even after a very successful decade on the field and another Super Bowl win, the future was bleak.

Executive committee members Pete Platten and John Underwood, who both were bankers, told Harlan the money would run out very soon.

"They both said to me, 'Bob, as we look ahead five years, look at where the costs are going to go, to what kind of revenue we can expect to bring in, we're going to have to borrow $10 million just to fund our operations.' I just couldn't let that happen," Harlan said.

Harlan spearheaded a bruising campaign that saw stiff opposition to a tax, to a Brown County-only tax, to a tax to support a football team. In the end, the 0.5% county sales tax passed 54% to 47%, but going into the day of the vote, Sept. 12, 2000, Harlan said polls still were 50-50 on whether the tax would pass.

Some suggested he hold off for a year, to allow more time to build support. Harlan was convinced the Packers didn't have a year, and, as it turned out, if held one year later, election day would have been Sept. 11, 2001.

"You can imagine people getting up to go vote on a football stadium and seeing two buildings in New York City on fire and other terror. So, thank God we did it when we did," Harlan said.

Earlier was better in another respect. Harlan said a representative of stadium consultant Hammes Co. told him if they had waited two more years to build, their $295 million project would have cost $600 million.

"The timing was perfect for us," he said.

Lifelong fan Craig Black said the changes to Lambeau Field might seem a lot for Green Bay, but they were necessary.

"There’s many, many people in Green Bay that say that we’re too big, that we should never have done that; but we have to do that, we have to keep up," Black said. "It’s not a matter of Green Bay losing a franchise, it’s also a matter of players want to come here, too. If we were going to stay as old school as some people would have wanted it, it would be hard to get free agents to sign a contract to come here."

More: A historical look at Lambeau Field and City Stadium, home of the Green Bay Packers

With Murphy at the helm, Lambeau campus growth continuous

Murphy succeeded Harlan as CEO and president in 2008, the team won another Super Bowl in 2011, and by then it was apparent that more changes needed to be made.

Experience showed that the original atrium format was not ideal. The Packers Pro Shop was enlarged twice before it was decided in 2012 to make more drastic changes. A major renovation resulted in moving the Packers Hall of Fame from the basement to the atrium's main floor and the restaurant from the second floor, also to the main floor. The Pro Shop, which was where 1919 Kitchen & Tap now is, was moved to the ground floor and enlarged. The northeast face of the stadium was redesigned to give the Pro Shop a higher profile, and the American Family entrance was added on the east side.

The Packers liked those results so much, they've pretty much not stopped making changes and additions since. A few of the changes included adding the south end zone seating and club areas, building new player facilities, a new security office, building the Johnsonville Tailgate Village, ongoing concourse updates, including renovated concession stands, and replacing the video scoreboards twice.

The recently completed addition on the east side of the stadium, which provided new offices for football staff and additional indoor practice space for players, cost $90 million.

Murphy announced a new construction project during the annual shareholders meeting on July 24. The offices the football staff occupied before moving into the new section will be renovated. The offices are 20 years old and in need of updating, Murphy said.

In addition to changes to the Lambeau Field property in Green Bay, the Packers, shortly after Murphy took over, bought up land around the stadium, mostly in Ashwaubenon, for which they paid more than $63 million. The land to the south is parking lot, but the land to the west is the 45-acre Titletown development, a commercial, residential, recreational and entertainment district owned by the Packers. Running down the middle is a 10-acre park that includes a sledding hill, skating rink, free playgrounds and a full-size football field.

The Packers have said Titletown investment will be about $300 million when complete, although some of that will come from Packers' partners, such as Commercial Horizons, Kohler, Hinterland Brewery, Bellin Health and Microsoft, among others.

Titletown includes restaurants, medical facilities, townhouses, apartments, and TitletownTech, a partnership with Microsoft that helps new businesses grow and thrive.

The Packers helped pay for their building programs with two stock sales since 2000, raising $130 million. The NFL prohibits the team from using stock sale income for football operations, so it all goes into improvements for fans, such as the new video boards or renovated concession stands.

Although the NFL has become very much a living room sport, and very, very rich because of that, Murphy believes the game-attending fans deserve to be remembered.

"The money (from media deals) is tremendous, but we still need to be sensitive to the fans," he said.

Packers seek balance between fans, other teams' owners

With the Packers raising tickets prices every year and charging going rates for merchandise, concessions and services, some fans question how sensitive the team really is. The Packers have one of the longest season-ticket waiting lists in the league, so seemingly have not reach a tipping point. Murphy says the Packers aim for prices just above the midpoint in the league, high enough to make other teams, who share in the take, happy, but not so much they price out fans.

"We are a very unique franchise," Murphy said. "We are so public that I think people really have this connection to the team. They want us to be successful. They want us to make financially good decisions, but they also want to be as affordable as possible. That's kind of the balancing act we deal with."

Upgrades and expansion will continue, although the addition of more seats won't happen. Lambeau Field already has the second-largest regular-season capacity in the league, about 81,000, despite being the smallest market by far. Lambeau trails only MetLife Stadium, home to the New York Giants and Jets, who are in the NFL's largest market.

"I think we have to continue to invest in the facilities and the stadium. When you go around the league, it’s very obvious when teams and communities don’t continue to invest in the stadiums, they fall apart," Murphy said.

"The stadium, we’ll continue to invest in that. The concourse renovation, I think we are up to seven or eight phases. I think that’s really going to be well-received by fans. It gets people in and out a lot more quickly. That’s not as visible as the video boards and some of the other things we’ve done."

Murphy will retire in two years and his successor will face his own set of challenges, Harlan said.

"The challenge we faced was the stadium. The challenge this group faced was what do you do around the stadium?" Harlan said. "The next group that comes in here, they're going to face a brand new challenge."

Contact Richard Ryman at rryman@gannett.com. Follow him on Twitter at @RichRymanPG, on Instagram at @rrymanPG or on Facebook at www.facebook.com/RichardRymanPG/.

This article originally appeared on Green Bay Press-Gazette: Packers' investments in Lambeau, other projects top $1 billion