'The ones who fixed it.' How Don Silas, IU Ten sacrificed for equal treatment of Black players.

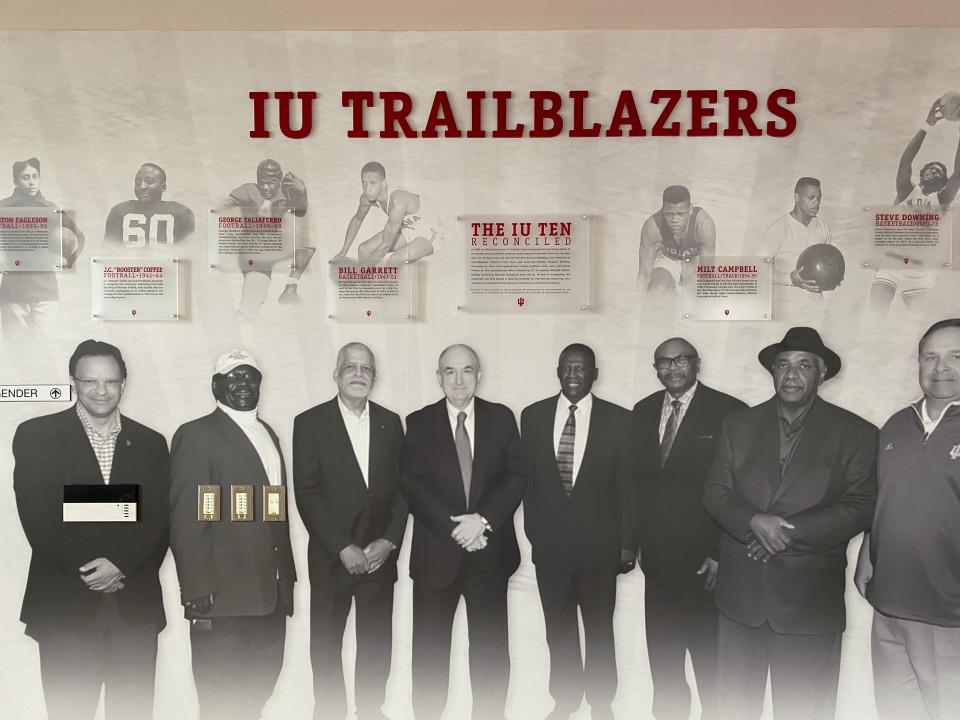

BLOOMINGTON – Just around the corner from the west elevator on the fourth floor of Memorial Stadium’s North End Zone facility, in the upper level of IU’s Henke Hall of Champions, a mural stretches nearly the entire length of a 12-foot wall.

Embossed atop the design are the words “IU TRAILBLAZERS,” all in capital letters. Athletes honored underneath include George Taliaferro, the first Black player drafted into the NFL; J.C. “Rooster” Coffee, who integrated the university swimming pool in the 1940s; Bill Garrett, IU’s first Black basketball player; and Milt Campbell, the first Black decathlon Olympic gold medalist.

But one image dominates the mural itself — eight men standing shoulder to shoulder, smiling for the camera. Their occasion is celebration, but scars still fill the empty space. Lives spun sideways. Dreams deferred. Dreams denied.

Among the eight are five members of the IU Ten, 10 Black players that boycotted and were eventually dismissed from Indiana’s football team in 1969 in protest of treatment on account of their race. Ten Black players who took a stand, walked away and never came back.

“It's amazing when you find out you were a victim of something impossible. Who could have fixed that then?” Donald Silas said. “We’re the ones who fixed it. … There’s tangible evidence of what we did to make change.”

In that picture, furthest left among them stands Silas. Chest out, smile wide, wearing a white turtleneck and a crimson blazer, Silas still looks in the photo so much the hard-hitting linebacker who came to Bloomington in 1967.

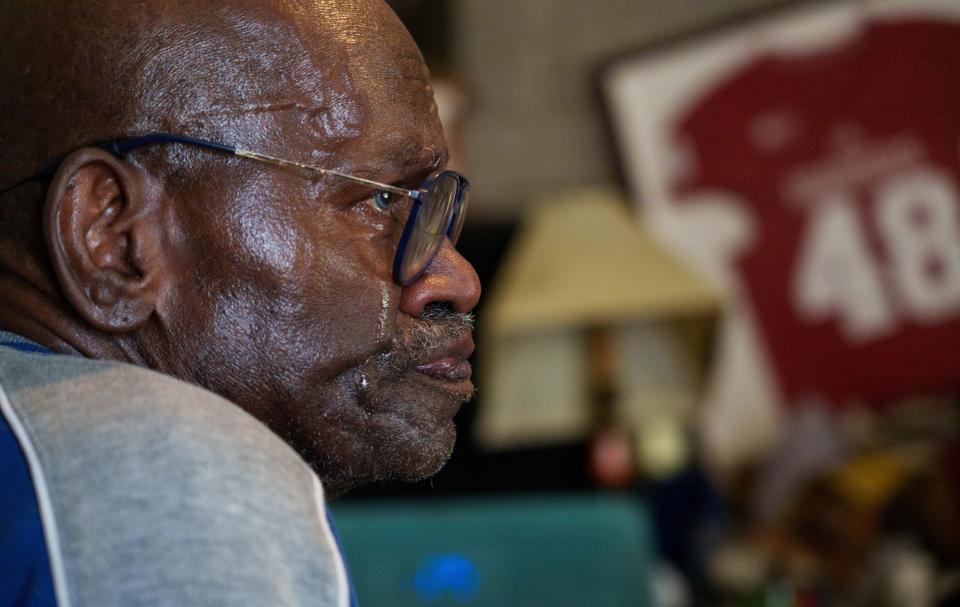

Silas was — is — one of the Ten. Few things make him so proud as that mural, even as so few things have so profoundly affected his own life as the ordeal he and his teammates endured more than a half-century ago.

“It was a huge sacrifice,” he said, “for all of us who were involved.”

There is so much more to Don Silas than that fraught week in 1969. He has a remarkable story to tell, of adversity and triumph and pain and redemption. And he wants to tell it now, while he can, because Don Silas is dying.

A hard-hitting, up-and-coming star

Silas came to Indiana University in 1967 from Emmerich Manual High School on Indianapolis’ south side.

He actually spent part of his childhood in Haughville, living at times without hot water or new clothes for school. In an interview with IndyStar in November 1968, Silas admitted he initially planned to quit high school when he turned 16. But then-Manual coach Noah Ellis helped Silas realize he could play collegiately, prompting him to redouble his academic efforts and eventually sign with Indiana.

At Manual, Silas played fullback and linebacker. Across three high school seasons, Silas gained 2,338 rushing yards and was named a South All-Star in the first Indiana Shrine Bowl following his senior year. An August 1967 IndyStar article shows Silas holding a football alongside, among others, Washington track star and state champion Larry Highbaugh, who played with Silas at IU, participated in the boycott as well and was eventually inducted into the Canadian Football Hall of Fame.

“Larry went to Washington. They had great teams there, like we had at Manual,” Silas told IndyStar in an interview last week. “We thumped them, and they thumped us back the next year."

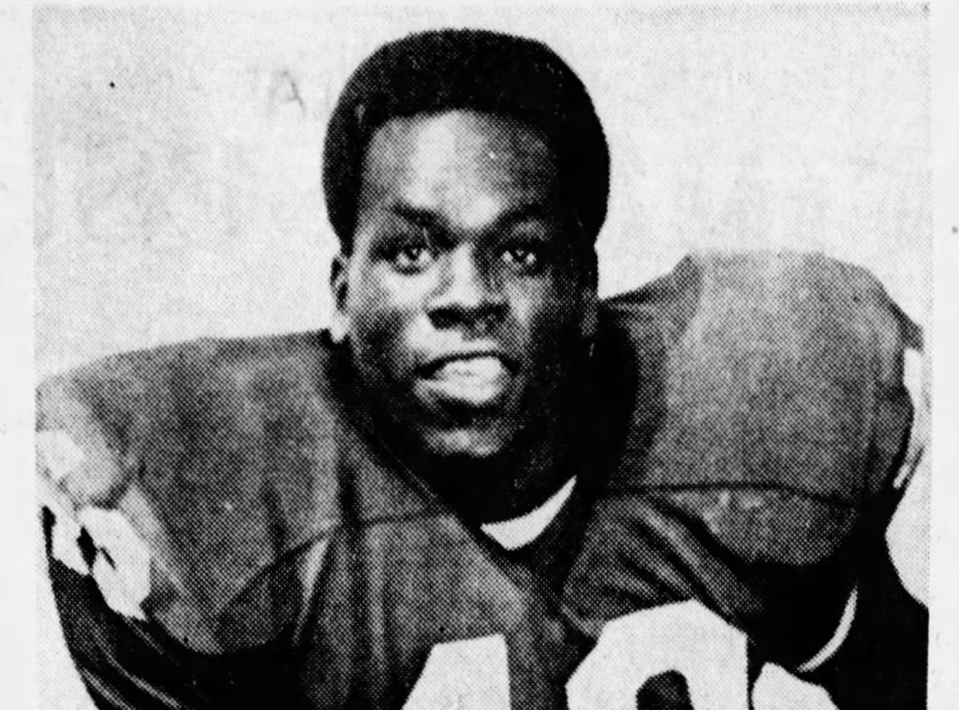

In Bloomington, Silas settled at linebacker. He hit hard and he liked it.

“They knew me as a bone jarrer. I loved the hitting. That was my forte,” Silas said, describing his preferred technique. “A lot of hits I did are illegal now.”

“I would bow my neck, and this,” he said, pointing to his face, “is like a battering ram.”

As a sophomore, coach John Pont and his staff entrusted defensive signal calls to Silas even though he was playing his first varsity season (freshmen weren’t eligible then). Silas became a regular on defense for a program fresh off its first Rose Bowl. Indiana’s 1968 season statistics even credit him with one kickoff return.

When IU’s basketball program brought Washington star George McGinnis to campus for a visit, Silas served as his host.

The kid who once figured he might not finish high school was thriving in college. An IndyStar article written in advance of the 1968 Old Oaken Bucket game painted Silas as one of IU’s up-and-coming stars.

“If Indiana does not win Saturday,” IndyStar assistant sports editor John Bansch wrote on Nov. 20, 1968, “Silas’ pride will be injured, just as well the pride of the rest of the Hoosiers. That, however, is something that heals with time. Life is a much bigger battle, and Don Silas is winning that struggle.”

The IU Ten makes a stand

Indiana started its 1969 season with a rout of Kentucky, before absorbing defeats at the hands of Cal and Colorado.

Then, the Hoosiers won three of four, all in conference play, the last victory a 16-0 shutout at Michigan State. After a 6-4 season followed the Rose Bowl appearance in 1967, the Hoosiers had positioned themselves in the thick of the Big Ten race in ’69.

That was a turbulent time in American history, and Bloomington felt it.

Robert Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King had both been assassinated the previous year. The Vietnam War cleaved a deep fracture into the American social consciousness. Protests and demonstrations were held regularly, sometimes daily, in Dunn Meadow on the west side of campus.

And in IU’s football locker room, long-held frustrations among Black players over perceived mistreatment on account of their race began to bubble over.

“We were still in the Jim Crow days back then,” Silas said. “In ’54, it had only just changed that it wasn’t illegal to have Black people in greater numbers. I mean, against the law. The Supreme Court. How do you fight that? Well, you fight it with something that hurts.”

On the Tuesday leading up to a Nov. 8 home game against Iowa, all 14 of IU’s Black players boycotted team practice.

Among the boycotters were some of Indiana’s most productive players.

Highbaugh, an explosive kick and punt returner who would complete the Big Ten’s first Jesse Owens slam — 100-yard dash, 220-yard dash, 440-yard relay and long jump — in 1969.

Clarence Price, a defensive starter, also from Indianapolis.

Mike Adams, a linebacker who hit so hard teammate Mike Deal nicknamed him “A-Bomb.”

Benny Norman, a defensive back from Florida who posted five interceptions in 1968.

And Silas, by then a fixture on the Hoosiers’ defense.

The 14 players expressed concerns they were mistreated compared to white teammates. They believed Black players were intentionally “stacked” at certain positions, so while the roster might reflect greater diversity, very few Black players would even be on the field at the same time. And they believed their playing time affected by the color of their skin.

“It was painstaking to play under that system,” Norman told IndyStar in a 2020 interview. “I don’t think (Pont) really wanted it that way. I don’t think he had a choice. … IU did not play their best ball players. Trust me.”

Writing in the Nov. 7, 1969, Indianapolis News, Lyle Mannweiler described Pont as sympathetic to his players’ concerns.

“Pont, who met earlier in the day with the 10, said he felt the Black (players) were sincere in their actions,” Mannweiler wrote. “‘For them it is real, and they are deeply concerned,’ he said.”

In later years, Silas said, players came to believe there was external pressure on Pont to follow certain unwritten rules regarding the handling of Black players. In the moment, all they could see was, as Norman said, a team holding its best lineups back, for reasons understandable only through one lens.

“‘They’ve got you behind Mike Adams?’” Silas said, becoming emotional as he relayed an example of players’ frustrations. “‘They’ve got Mike Adams behind you?’ Neither of those were (wise).”

Citing a team rule, Pont announced any player who did not return to practice Wednesday would be dismissed from the team.

Four came back. The rest became known as the IU Ten.

IU lost its last three games of the season: to Iowa and Northwestern, which each finished 3-4 in Big Ten play that year, and to Purdue, which finished 5-2. Had Indiana beaten the Hawkeyes and Wildcats, it would have played the Bucket game that year for a chance to win a share of the conference title.

None of the IU Ten ever played football at Indiana again.

Trying to find path after football

Life dealt each of the Ten his own hand after Indiana.

Pont and the university agreed to honor their scholarships. Some stayed at IU, like Highbaugh, who became an All-American on the track team before pursuing professional football in Canada.

Silas struggled.

He tried to make a go of the sport in Canada, where he spent time under Jay Fry, an assistant in Ottawa who had been IU’s offensive coordinator during the Rose Bowl season. Fry, Silas said, treated him well, but Silas found too many of the same broader attitudes toward Black players north of the border.

According to newspaper reports, he spent time with the Indiana Caps of the Midwest Professional Football League in 1972, but eventually, the sport fell away. Football had been the anchor in his life, the thing that gave it purpose and direction. Without it, Silas couldn’t find his footing.

He struggled through addiction, yet also triumphed in beating that addiction, mentoring others along the same journey and eventually going back to school. With the help of Indiana’s original promise in 1969, Silas graduated from IUPUI in 1981 with a bachelor’s degree in physical education.

Along the way, he found various passions.

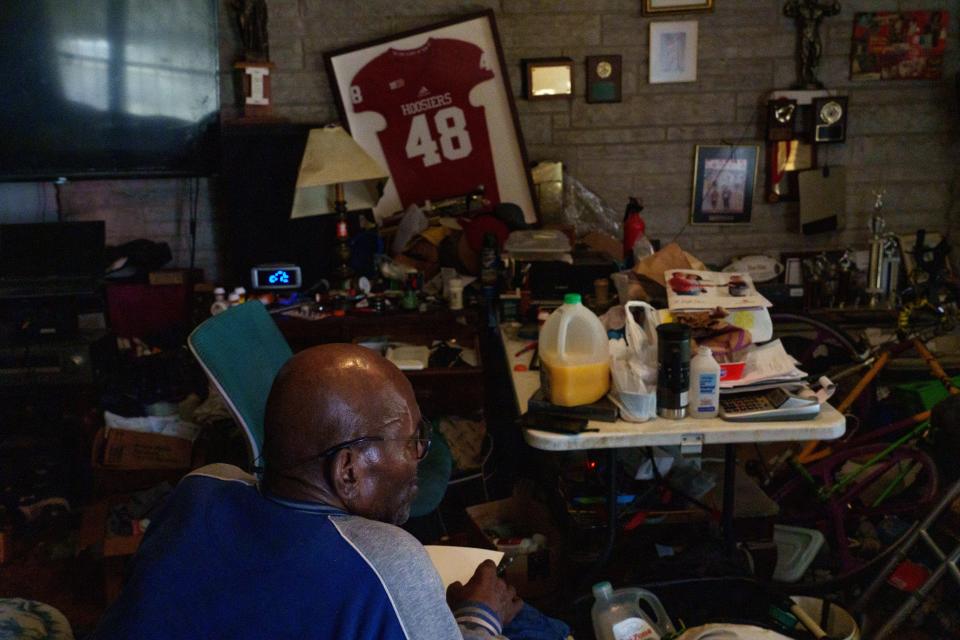

He became a champion bodybuilder, his house today still adorned with trophies and medals from his career. So accomplished was Silas in that passion, when he took his degree and went to work for the Indiana Department of Corrections, he trained inmates in bodybuilding.

“We had three national-championship teams while I was at Pendleton,” Silas said. “I could bring in outside groups and referees who were sanctioned by the amateur bodybuilding association and the amateur weightlifting association. Those guys, they just trained all the time.”

After he left Corrections — action Silas said came after he was perceived to be too much of an advocate for inmates — Silas took that advocacy a step further. He put himself through law school, also at IUPUI, and in 1996 graduated with his Juris Doctorate. The tassel from his mortarboard still hangs off a lamp in his front room.

Silas specialized in criminal and personal injury law, and in particular worked to lend a voice to prison inmates who felt they were being exploited. Advertisements for his practice in the News in the late 1990s described him as a “prisoner grievance specialist.”

Yet Silas still struggled to fill the hole football left. The all-in effort he poured into every passion or profession acted as a surrogate for the thing he’d lost.

“I really wanted to play football,” Silas said. “Anything that I achieved athletically helped me feel best.”

After bodybuilding came bicycling.

Silas joined the Central Indiana Bicycling Association. Atop a custom-built steel-frame Colnago he later had painted purple, yellow and green for a bike ride through Louisiana during Mardi Gras, Silas tackled 100, 200 or 300 miles at a time.

He organized a century (100 miles) originating at the prison in Pendleton, where he worked, that lasted more than a decade. Then there was the Columbia 260, a grueling ride from St. Louis to Kansas City.

Silas’ greatest achievement on the bike might have been the famous Paris-Brest-Paris, 1,200 kilometers through the French countryside from the capital to the coast and back.

Riders must qualify for the event, which is timed and disqualifies any participant who does not finish within the 90-hour limit. Cyclists are required to complete a series of brevets — long-distance cycling challenges — of 200, 300, 400 and 600 kilometers under time limits and controlled conditions before they are accepted into the field.

Across two years, Silas finished his brevets before flying to France, and competing in the famous event. Something else to fill the void.

“It seems like as long as I was consumed by something and needing something, the drive was there,” Silas said. “It’s like an itch you can’t get to, but you keep at it. You rub on the outside and bang it. You just want it to stop. The only way to stop it was when I was getting a trophy or I was getting a medal. I’ve got a whole box full of medals and T-shirts.

“Somebody joked to me, ‘You rode 260 miles for a T-shirt?’ Only when I hear somebody else say it does it sound mad. To me, it sounds right.”

Giving back

After several years practicing law, some under his own shingle and some working in the law offices of Nathaniel Lee, Silas went back into teaching.

Legal work did not, as Silas put it, scratch that itch. But in teaching, Silas finally found something that could.

Growing up poor, Silas remembers classmates teasing him over things like his clothes. He didn’t understand then the pain it caused, but he sees now “how damaging that was.”

“I was that kid,” he said, “and I couldn’t have told anybody what I needed back then.”

Yet he also remembers the adults who helped steer him through it. Not least John Patterson, his grade school P.E. teacher. Silas still chokes up remembering Patterson buy Silas his first pair of new dress shoes.

When Silas returned to teaching, he took the same approach with his students.

“Some of those kids, now, they’re teachers now,” Silas said, “and they call me Big D. ‘Mr. D, I’m so glad you taught me what you did. I teach my kids the same things and they’re doing well.’ And that’s satisfying.”

Reconciliation with IU

Nine years ago, Silas gained another form of closure.

Initiated with the university by both Adams and activist Trish Geran, five members of the Ten — Silas, Adams, Norman, Price and starting offensive tackle Charlie Murphy — sat for four days in April 2015 with IU officials.

Representing Indiana were Athletic Director Fred Glass, IU Vice President for Diversity, Equity and Multicultural Affairs James Wimbush, faculty athletics representative Kurt Zorn, former trustee Clarence Boone, Associate AD Anthony Thompson and Associate AD/Senior Woman Administrator Mattie White.

In his book, “Making Your Own Luck,” Glass (who retired from Indiana in 2020) described the summit as “among the most moving and poignant days of my professional life.”

“We met several times, often over meals, and each of the IU Ten shared their very personal and emotional stories of the boycott, what led to it, and its aftermath,” Glass wrote. “We cried. We talked. We listened. We hugged. We connected. It was powerful and far exceeded my most optimistic expectations for mutual understanding and, ultimately, reconciliation.”

An April summit led to wider reconciliation, a final tearing down of the walls built by the boycott, and an easing of the pain members of the Ten absorbed during that fateful, pain-filled week in 1969.

Silas describes the experience now as “a sincere effort” on the university’s part. That echoes sentiments he expressed in 2015, when he said in a news release: “I feel like the cloud has lifted. I’m glad that coach Pont and I were able to make peace by both saying we were sorry before he passed.”

As part of the reconciliation, each member of the Ten was honored with a framed IU jersey bearing their number. Silas’ still hangs on the wall of his Indianapolis home, near a football mounted on a stand bearing the final score of the 1967 Old Oaken Bucket game — Indiana 19, Purdue 14 — the win that sent the Hoosiers to the Rose Bowl.

The end

They are, along with his Rose Bowl ring, among Silas’ most treasured possessions. Some will go to family. He plans to donate the rings to Lee’s law office. Many of his other things will go to charity when he’s gone.

Because Don Silas is dying.

An eight-day stay in Methodist Hospital earlier this year turned up terminal liver cancer. Doctors gave him months, at best.

As soon as he was handed his diagnosis, Silas’ legal background took over. He’s been able to address power-of-attorney concerns, sign over his car to his sister and secure a rescue home for his four chihuahuas, Freddie, Chevy, Hoppie and Granchile. Chevy, the oldest, has been with him 20 years.

Only his funeral arrangements need final funding, with a GoFundMe page set up to assist that effort.

Silas’ chief request in sitting for this story was that it center on the mural adorning the Henke Hall of Champions wall.

“You’ve got,” he said, “to mention that.”

Silas called it “the most selfless sacrifice of my life.” Its pain never fully left him, but the legacy he sees today of greater accountability and athlete empowerment makes him proud. Because what is a person if not the sum of their triumphs through adversity?

“Those who came to Indiana after the boycott,” he said, “have no idea how different things are now.”

It’s important to Silas that be a core piece of his legacy. He took the hard road, more than once, but he never backed down from it.

Which makes the picture, from that day in 2015, so important to him — Silas standing between Tom Crean to his right, and Norman to his left. Then-IU President Michael McRobbie is present, as is former coach Kevin Wilson. Between them, Adams, Price and Murphy.

A moment long overdue, tremendously important, frozen in time and affixed on the wall inside Memorial Stadium forever.

Follow IndyStar reporter Zach Osterman on Twitter: @ZachOsterman.

Members of the IU Ten football boycott in 1969

Mike Adams

Greg Harvey

Larry Highbaugh

Gordon May

Charlie Murphy

Benny Norman

Bobby Pernell

Clarence Price

Don Silas

Greg Thaxton

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Indiana football: Don Silas, of IU Ten, reflects on boycott, legacy