Not a gimmick, Air Raid has taken over college football — including old-school Big Ten.

Amid the din Texas A&M’s Kyle Field becomes during the fourth quarter of a close game, Graham Harrell stood facing the climax of a defining performance early in his career.

Harrell was already three touchdown passes to the good. He would end the day with an eye-popping 392 yards, and complete all but 13 of his 45 attempts.

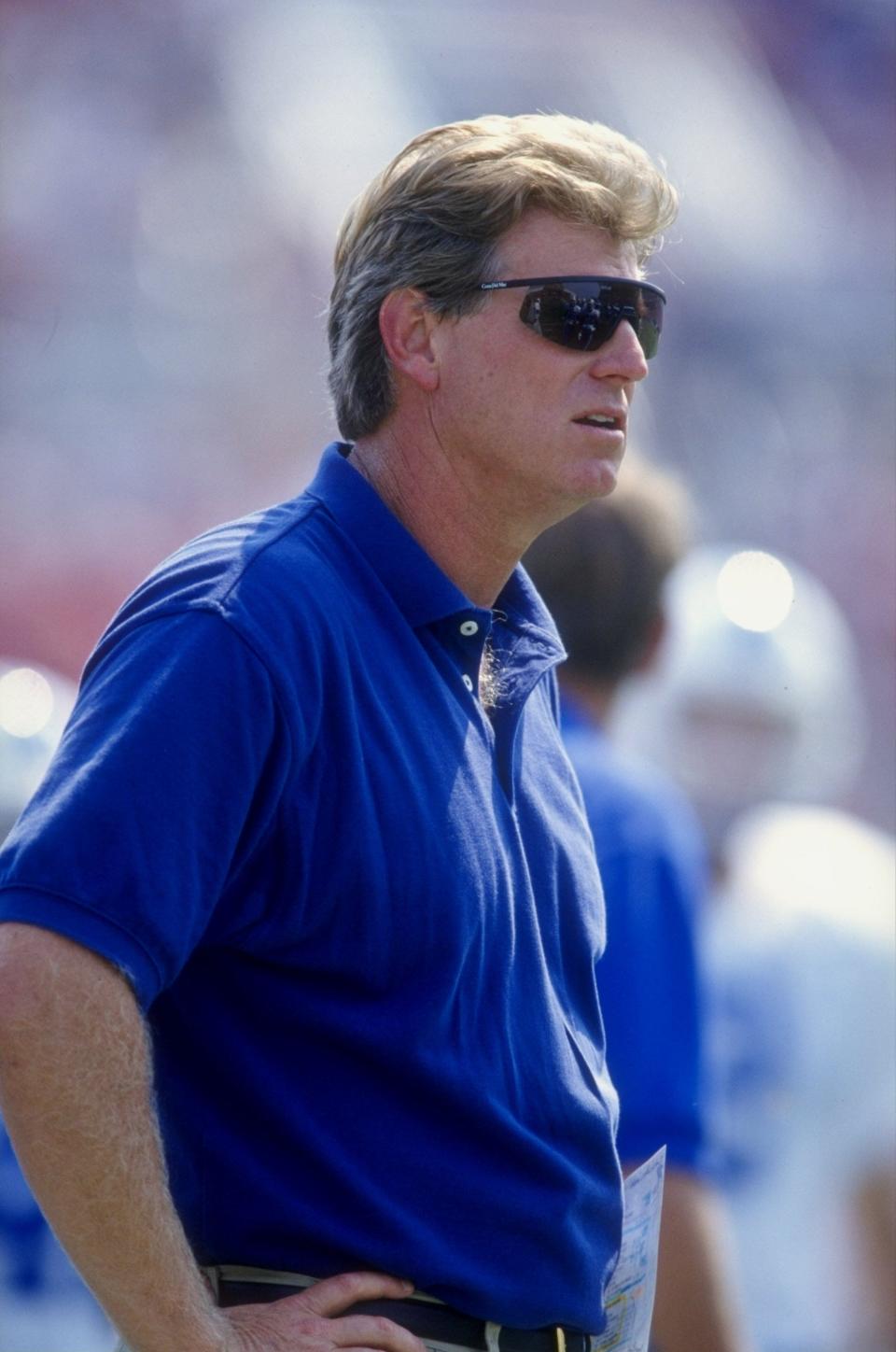

Yet when — the Red Raiders facing a crucial fourth down on their final drive trailing by three — Texas Tech coach Mike Leach turned to his sophomore first-year starter and said, in effect, you call the play, Harrell was stunned.

“Coach Leach signals base check, which is just, get in two-by-two and call the play,” Harrell recalled. “A hundred thousand people screaming. I’m a sophomore. You want me to call it? Really?

“And then we convert it, and end up winning that game on a fade.”

The Red Raiders won eight games that season, including an overtime victory against Minnesota in the Insight Bowl. Two years later, they would climb to No. 2 in the country.

What Harrell came to realize was the offense that helped Texas Tech achieve all those things, the one for which Leach became so famous, was built precisely for moments like that fourth-down call at A&M. It might have seemed risky to Harrell, and to many outsiders, it was all just a novelty, but for Leach, that was his offense operating exactly as it should.

Could either man have known then the course the Air Raid was already on — to take over football entirely.

“There’s parts of it everywhere now,” IU offensive coordinator Walt Bell said. “At every level of football.”

How Hal Mumme created the Air Raid

The Air Raid started with a scheduling quirk.

In the mid-1980s, Hal Mumme worked as offensive coordinator at the University of Texas at El Paso. The Miners competed in the old Western Athletic Conference, the class of which at the time was LaVell Edwards’ powerhouse BYU program.

UTEP followed BYU through the schedule in those days, meaning every time Mumme got film of an upcoming opponent, he watched them play the Cougars.

BYU was known at the time as the cradle of quarterbacks, thanks to alums like Steve Young, Jim McMahon, Marc Wilson and Ty Detmer. The more film Mumme watched of Edwards’ high-powered passing offense, the more he found himself adapting it into his own.

“I started cutting it up and looking at it,” Mumme said, “implementing some of the stuff they were doing.”

In 1985, the Miners won just one game — a 23-16 home upset of No. 7 BYU.

UTEP managed to pull it off with an unorthodox defense, dropping as many as eight defenders into coverage each snap. And the Miners did it with an offense BYU coaches recognized clearly. And they should have. It was patterned after their own.

“Underthrown back-shoulder passes, Y cross, stuff like that,” Mumme said. “They recognized that.”

At the end of that season, UTEP let its staff go. At the annual coaches’ convention, Mumme ran into BYU assistants still impressed by his ability to beat them at their own game.

They extended an open invitation to come to Provo any time Mumme wanted, and even briefly discussed bringing Mumme on staff to replace outgoing quarterbacks coach Mike Holmgren. Mumme wound up dropping down a level, where he could run his own program as head coach at Copperas Cove High School in Texas.

But for the next three years, he’d take the Cougars up on their offer. Mumme traveled to Provo before spring practice each season, sat in on film and took notes. He’d go back to Copperas Cove, install what he’d developed from his visits to Utah, run through it, then return in the summer and refine his thinking.

And thus was born the offense that became known as the Air Raid.

Mike Leach joins the Air Raid party

That was the first of what Mumme called three big “epiphanies” in developing his offense. The second came after three years at Copperas County, when Mumme took the head job at Division III Iowa Wesleyan.

By this point, Mumme had refined his offense past even what Edwards did at BYU. That meant turning many of the old run-to-pass football maxims on their heads, and redefining offensive line play.

The trouble was finding someone to do it.

“Big splits, play in a two-point stance, throw it 50 times a game and be backed off the ball a lot, (candidates) would just walk out of the room before you could finish the sentence,” Mumme said. “I decided to hire the smartest guy I could find, and that turned out to be Mike Leach.

Across the next nine years, the two became inseparable, Leach following Mumme from Iowa Wesleyan to Valdosta State to Kentucky. Leach would become a chief disciple of the Air Raid, and then a preacher himself, as head coach at Texas Tech, Washington State and Mississippi State.

He would carry with him one more of those epiphanies, this one from Canada by way of spring-league football.

Late in their time at Iowa Wesleyan, Mumme and Leach found themselves struggling to get opponents on their schedule. The Tigers had to play up to get games, but that pitted them against opponents with significantly more resources.

So, Mumme and Leach did what they always did when they needed a competitive edge — they hit the road. In those early years, when mainstream football still thought pass-heavy schemes a fad, they’d go anywhere coaches were throwing the football. Mumme became close with contemporaries like June Jones and Mouse Davis, run-and-shoot evangelists who saw football in similar ways.

This time, soul searching took Mumme and Leach to Orlando, where eventual five-time Grey Cup winner Don Matthews was coaching in an offseason league. As they walked out to practice, Mumme asked Matthews, “What’s the best drill you do out here?”

Watch bandit drill, at the end of practice, Matthews told him. It was two-minute offense but sped up, and not necessarily just designed for two-minute situations. Mumme and Leach came to the same conclusion at once — their edge would be a no-huddle offense. Leach looked at his head coach.

“We’re gonna do this all the time, aren’t we?” he asked.

Key to Air Rad: Keep it simple

Walt Bell walked in the door at Middle Tennessee State just as Larry Fedora walked out of it.

A high school quarterback, Bell had committed to play wide receiver at Middle Tennessee knowing full well the offense Fedora ran. The Blue Raiders were renowned for their spread, high-tempo, one-back shotgun offense built on Air Raid principles. When Fedora left for Florida and Blake Anderson took his place, not much changed.

Even then, just 20 years ago, the Air Raid was seen as a fad the sport didn’t believe could be supported by high school talent (where would you get the quarterbacks to run it?) or professional buy-in (it was seen as too simple).

“When I played at Middle Tennessee State, we were looked at like a triple-option team,” Bell said. “We were a fad, we were lesser, we had to gunk up the game to make it equitable for us.”

But by this point, the Air Raid was beginning to gain traction.

Leach left Kentucky for Oklahoma, coached one year under Bob Stoops, then went to Texas Tech. His Red Raider teams threw the ball all over the field, and fad or not, it looked like fun.

That trait followed the Air Raid to the top. Speeding up tempo meant more snaps per game, which meant more stats to go around. And forcing defenses to cover the entire field opened holes talent alone couldn’t close.

“It doesn’t really matter what coverages they run. You feel like you’ve got answers,” Anderson, now head coach at Utah State, said. “You don’t always have to have better athletes than the team covering you. Numbers and leverage and execution can help you be effective.”

Even coaches like Anderson, who didn’t necessarily have a dedicated Air Raid background, were beginning to embrace it.

They found the mesh points between Mumme’s offense and the burgeoning spread-tempo, option-heavy attacks run by coaches like Rich Rodriguez. Anderson and Darin Hinshaw, his co-offensive coordinator at MTSU, spent a week observing Sonny Dykes while Dykes was on Leach’s staff, as they adapted the offense to their own thinking.

The Air Raid was spreading, and the sheer numbers were staggering. Harrell is still one of the five most prolific passers in FBS history. Five of the 20 best single-season passing totals in that division belong to Leach quarterbacks, and a sixth, Patrick Mahomes’ 5,052-yard 2016 season, came under former Leach quarterback Kliff Kingsbury (who himself is also in that top 20).

“When I went to Copperas Cove, the four best athletes in the school didn’t play football,” Mumme said. “I said, ‘Why don’t y’all come play football. I’ll let you play your other sports as well.’ They said, ‘Football’s not fun,’ so we set about making football fun.

“They started as sophomores. As seniors, they were the all-district quarterback, one all-district receiver and one all-state receiver.”

Coaches found it easier to recruit athletes to an offense that promised touches and space. Programs found fans enjoyed the basketball-on-grass spectacle Air Raid games became.

Mumme’s Kentucky teams routinely scored in the 40s, 50s and even 60s, and the Wildcats upset ranked Alabama 40-34 in his first season. Leach had even more success in the Big 12.

“In the beginning stages, my dad was just trying to make it fun,” said Matt Mumme, who played for his father at Kentucky and is now offensive coordinator at Colorado State. “Why would you work 70-hour weeks if you’re not going to have fun doing it?”

Then there were the quarterbacks.

When football turned its nose up at pass-first offenses, especially at the highest levels of college and the pros, in the 1990s and early 2000s, conventional wisdom said it was because there just weren’t enough quarterbacks to run them. Passers with big numbers like Tim Couch and B.J. Symons were labeled system quarterbacks, in an offense Mumme and Leach had intentionally designed for simplicity.

“It took us probably from ‘86 until about ‘91, and then we took it to Valdosta (State) and repeated it,” Mumme said. “In that five-year span, we had to learn to make it simple, and keep our menu of plays to a bare minimum. Particularly when we started playing fast, you couldn’t overcomplicate things.

“I think that’s one of the worst things coaches do, to this day.”

They built the Air Raid on a handful of basic route combinations — calls you’d recognize today like four verticals, Y cross and mesh — and then a few key principles.

If a wide receiver was single-covered, that was an opportunity. If a linebacker rolled the wrong way, that was an opportunity. Defenses were forced to spread themselves thin, to cover the entire field. Tempo made communication more difficult, and the way the offense isolated defenders made them reveal their intentions more often.

So long as the quarterback was conditioned to recognize and check to the right play pre-snap, the Air Raid could operate on those base plays and concepts indefinitely.

“Mike got pretty famous the last 20 years or so for having his little play card in his hand,” Mumme said. “I had mine on a sheet but I just stuck it in my pocket, because I had it memorized, because it was that simple.

“Players appreciate that. If it’s that simple, all they have to do is use their athletic ability and it becomes a lot more fun for them.”

No one more so than the quarterback.

Harrell might have been surprised that day in College Station, when Leach put the game in his hands. But Leach will have known in that moment his offense worked best when he let his quarterback figure it out.

“If there’s one guy on the team you’re going to put that responsibility on, that would be your guy,” said Harrell, now offensive coordinator at Purdue.

Slowly, steadily, Mumme and Leach began building impressive coaching trees. More people in the sport realized the Air Raid was simpler, more effective and more fun. It was about to get the last boost it needed.

Air Raid makes it to the Super Bowl

What’s known today as flag football supposedly began in the military during World War II. American soldiers, seeking fun ways to stay fit without injuring themselves, began playing what they called “touch and tail football,” which eventually evolved into the sport you probably played in elementary and middle school.

In the 1990s, Dick Olin, the head football coach at Baytown Lee, east of Houston, began using the concept as a training method.

Olin, whose offenses bent toward the pass, stripped the field of linemen and contact. He implemented flag football-like rules, and he started running 7-on-7 passing tournaments.

One of the last bricks in the football’s evolutionary wall was laid.

“The 7-on-7s, that’s what’s changed everything,” IU coach Tom Allen said.

As it spread, 7-on-7 football first filled an offseason hole. In northern and Midwest states, where the weather was too cold for spring football, players used 7-on-7 as a substitute. And where football was king, here was a new way to train all year.

From there, nature took over.

After years spent watching Mumme at Copperas County and Leach at Texas Tech, Texas — arguably America’s most talent-laden football state — fell in love with spread offense and Air Raid principles. Embracing 7-on-7 football smoothed the transition.

As went Texas, so went the country. More schools passed more. More players, not just quarterbacks but running backs, wide receivers and tight ends, grew up in offenses like the Air Raid.

Football filters up. The game followed the talent right to Mumme’s offense.

“It gives you the reps you need … and the ability for us to be able to have more states let high schools do things whether it’s in the true spring or in the summertime,” Allen said. “Now, because of that, it’s a simple enough system where kids can make reads, make adjustments, and because they’re doing it so much with 7-on-7, it’s elevated the whole level of play of quarterbacks and skill guys.”

What high school coaches also found, as players gained a better environment to train for pass-first offenses, was that the Air Raid’s simplicity wasn’t a vice.

Most high school coaches couldn’t control their talent pools. They needed to maximize what athletes they had, just as Mumme had realized that first year at Copperas County. And as coaches like Anderson and Phil Longo showed the sport it was possible to run effectively out of the spread with wide line splits and run-pass concepts, dual-threat quarterbacks became an easy fit.

“One of the things that’s helped it evolve and changed it so much in the college game is all the 7-on-7 stuff,” said Carter Whitson, who played at Oklahoma and coached at IU before guiding Martinsville to consecutive winning seasons running a pass-based offense like the ones he saw under Kevin Wilson.

“These kids can do this stuff so much more and it is relatively simple,” said Whitson, now head coach at Edmund North High School in his native Oklahoma. “Just the simple calls, the simple protections, the choices of how to run these routes, to go where they’re not, has really just made it to where a lot more people can run it.”

What the option once was to high school football — a talent leveler that’s easy to teach and drill — the Air Raid has become.

Today, Mumme sits at the base of one of college football’s most impressive coaching trees. West Virginia’s Neal Brown played for him at Kentucky. Leach, Mumme’s earliest disciple, counts everyone from Dana Holgorsen (Houston), to Dykes (TCU), to Lincoln Riley (USC), to Sonny Cumbie (Texas Tech) among his former players or assistants. That is hardly an exhaustive list, the branches of that tree multiplying again and again.

Just as numerous are coaches like Anderson and Longo, now with Luke Fickell at Wisconsin, who fell in love with the Air Raid enough to make it their own. Wisconsin, an old-school offensive program in an old-school offensive conference, will run the Air Raid this fall. Bell even saw Air Raid concepts in the offenses that drove Kansas City and Philadelphia to their meeting in last season’s Super Bowl.

“You can see it,” he said, “at the highest levels of football.”

That’s what evolution looks like: A whole generation of coaches grew up on the offense once viewed as too niche, spreading it from conference to conference, from one level of football to the next, eventually usurping and replacing the old order.

“The reason I’ve got so many former players and staff members that are head coaches now, or coordinators, is because it’s the most fun they ever had coaching or playing, or both,” Mumme said. “It made the game fun again. I think it’s made it fun for fans and everybody involved.”

Follow IndyStar reporter Zach Osterman on Twitter: @ZachOsterman.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: How Air Raid offense has conquered college football, landed in Big 10