No one loves baseball like Jazz Chisholm – and the Marlins rookie is convinced the game will reciprocate

Jazz Chisholm knows that baseball is difficult, that there remains a significant gulf he must cross to match his significant talent and overwhelming charisma to his production.

Right now, this is who Jazz is: A rookie infielder for the Miami Marlins whose stat line says his production is just above league average, but his swag suggests he’s anything but.

This is who Jazz could be: A dynamic, powerful, five-tool force, whose desire to disrupt the game could vault him atop the short list of burgeoning baseball stars with ever-elusive crossover appeal.

This is how he plans to get there: By sacrificing nothing – certainly not the vicious bat speed from his swing that ensures the home runs he does hit go very, very far. And certainly not the exuberance that vaulted him from the Bahamas to the big leagues, endearing him to fans and perhaps enabling him to join some of his athletic heroes – Kobe, LeBron, KD – as a wonder known only by one name.

And what’s the tune Jazz lives by?

“To this day,” he says, “I just always try to tell kids to be themselves. Don’t let nobody change you. You go out there and play the way you want to go play.

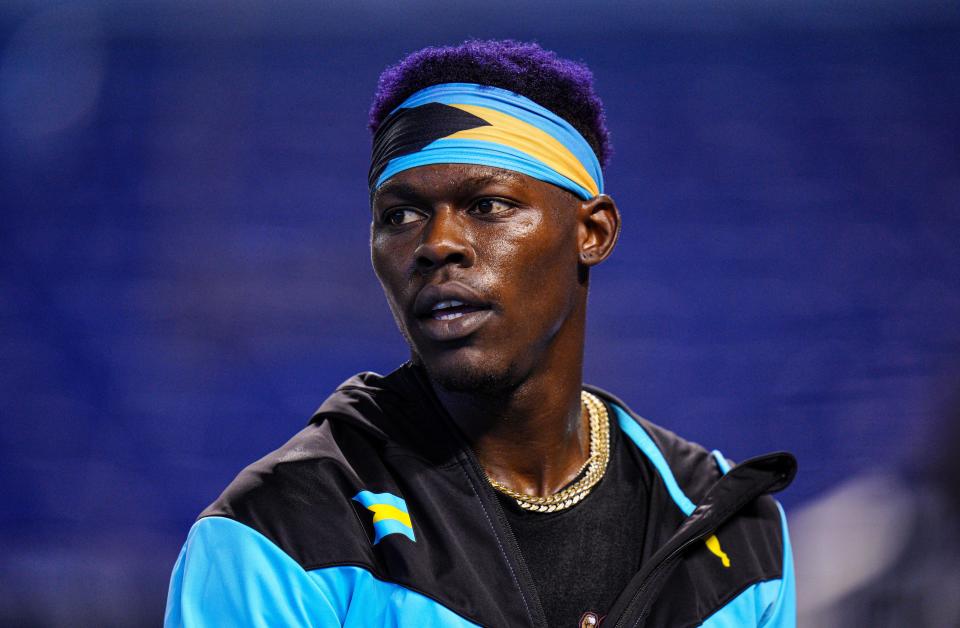

“That’s why I always do the crazy hair colors, I do my dances and I just have fun out there because I just want everybody to know, it’s OK to have fun on the baseball field.

“You know?”

If you don’t, you probably will soon.

'Why not bring it into the game?'

Perhaps you found out on Opening Day, when Chisholm fulfilled a promise made to Marlins ace Sandy Alcantara. Chisholm, whose hair changes color with the ease of South Florida weather patterns, was planning a platinum blonde look.

Yet as spring training wound down and Chisholm – who debuted on Sept. 1 in the pandemic-shortened 2020 – had a shot to make his first Opening Day roster, Alcantara had a suggestion.

Make the team, he said, and you dye your hair blue.

“I said, ‘I got you,’” Chisholm recalls. “It was history from there.”

Chisholm came through, breaking camp with the squad and showing up for the opener with a tone resembling a Louie-Bloo Raspberry Otter Pop.

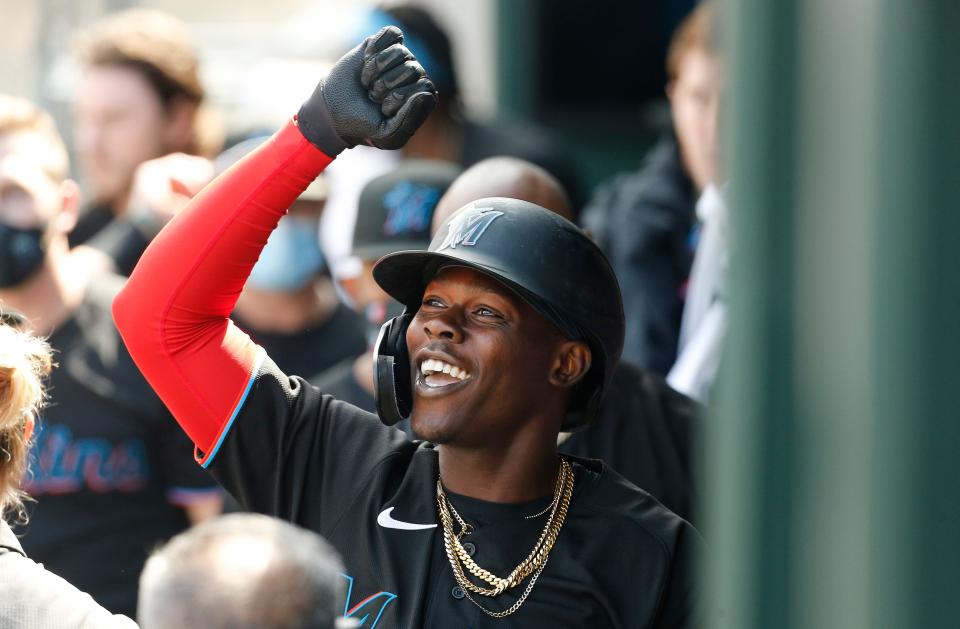

Perhaps you noticed a couple weeks later, when Chisholm hit his second home run of the season, a towering shot off Atlanta’s Charlie Morton, and then, befitting his significant basketball skills, debuted a euro step as he crossed home plate.

Contrived?

Nope. Just a part of his personality, reflexive as a fist bump or handshake.

“I will walk around the clubhouse euro-stepping on people,” he says. “I’ll be in front of someone and last second, I’ll give ‘em a euro, you know, like, ‘Get out of the way.’ It’s something I do all day, every day.

“So why not bring it into the game? Why not misdirect it going into home, and then step on it?”

It’s not like Chisholm is pimping home runs that scraped the top of the wall.

He is the only player this season to go deep on pitches of at least 100 mph, doing it first off the great Jacob deGrom on April 18 and then the Phillies’ Jose Alvarado a month later. He is, in fact, the only player with two such homers since pitch-tracking began in 2008.

Listed at 5-11 and 184 pounds, Chisholm – full name Jasrado Hermis Arrington Chisholm – seemingly manifested his skills by watching his grandmother play softball.

Yeah, Grandma could turn on one.

“The small person with the pop? Yeah, I think I got that from her, too,” he says.

Patricia Coakley, now 77, played on the Bahamian national softball team, and played the sport long enough for Jazz to see her compete both in slow- and fastpitch formats. He saw himself in her, from the aforementioned quick bat to the tenacious baserunning approach to her play at shortstop.

And so when Chisholm was barely old enough to hold a bat, he called dibs on the position, fully intending to never leave.

“I just loved seeing her play shortstop. I fell in love with watching her, too,” he says. “It was always like that from when I was probably 4 and 5 - just run straight to shortstop.

“Grandma’s a shortstop, I’m a shortstop.”

Clearly, he picked an excellent role model, though there weren’t many others locally. Just eight players from the Bahamas preceded Chisholm to the majors, with infielder Andre Rodgers – who played from 1967 to ’77 - the only one to hold down anything resembling a full-time role. Antoan Richardson was the most recent, serving largely as a pinch runner from 2011 to 2014, and he’s now a coach for the San Francisco Giants.

Young Jazz focused on his grandmother’s exploits and fixated on televised games featuring Ken Griffey Jr., Barry Bonds and Derek Jeter.

And was convinced he’d play on their level.

“I always told myself that I was going to be a big leaguer, from a very young age,” he says. “It was not really tough believing I was going to be a big leaguer.”

Chisholm played plenty of ball stateside as a child, often in Miami, and attended a prep school in Kansas for a spell, eventually signing with Arizona as an international free agent. While he’s sanguine about his own rise, he’s humbled when he ponders his impact back home.

“Every time I go to the Bahamas I see a little kid telling me, ‘Hey, you made me start playing baseball,’” he says. “It makes me smile nonstop when I hear that.”

They have a dynamic hero to follow, even if he’s an unfinished product. Chisholm is on pace to hit 20 home runs and steal 20 bases this season; he clubbed his ninth home run of the season Thursday night in a loss to the Washington Nationals, pushing his batting average to .258 and his OPS to .766.

With just 276 plate appearances behind him, Chisholm has room to grow. That makes him a good match for Miami, which acquired him from Arizona for pitcher Zac Gallen in 2019. “I love the people out here,” he says. “This is just the life that I feel like I was here to live. My kind of place.”

Fresh fish

The Marlins are 31-43 and lagging in the NL East, a pitching-centric club with a lineup that looks emaciated even within this season’s historically grim league environment.

Yet for a franchise dogged for decades by ham-handed ownership, they have a decidedly fresh feel.

They have a quietly beautiful ballpark still not yet a decade old, yet new owner Bruce Sherman bears none of the blame for bamboozling the city into a hideously bad stadium deal. In Jeter they have a CEO with star power but also patience, and the forward-thinking mentality to hire the first woman as a major league GM, the highly-regarded Kim Ng.

Alcantara and rookie lefty Trevor Rogers are worthy aces, with the injured Sixto Sanchez also capable of holding that role. At Class AA Jacksonville, pitching prospects Max Meyer and Edward Cabrera join outfielder J.J. Bleday, all consensus top 100 prospects nearing the big leagues.

In Miami, Chisholm defers to veterans such as Jesus Aguilar and Miguel Rojas, who when healthy nudges Chisholm to second base. From a baseball standpoint, Chisholm says he goes to great lengths not to “get cocky with the veterans.”

Yet they share a desire to keep things loose, from the clubhouse to the kicks; Rojas has long used social media to amplify his shoe game, while Chisholm has donned footwear celebrating concepts as disparate as Miami Vice and Oreo cookies.

Earlier this week, he debuted a gold chain that commemorated a remarkable leaping catch against the Tampa Bay Rays.

“The Miami Marlins’ whole roster right now – you look at what they’re wearing on their feet, even down to the coaches sometimes, it’s just straight heat, I’m not going to lie,” says Chisholm. “Everybody is just into that stuff – having the swag, having fun on the field.”

It all may seem a bit excessive for a second-division club, yet the Marlins also made the playoffs in 2020 and swept the Chicago Cubs out of them. Manager Don Mattingly says the veteran tone set by the likes of Aguilar and Rojas “helps your club create an atmosphere that guys like playing in.” He is confident Chisholm will develop greater consistency both in routine and performance, calling his development arc “pretty normal” for a first-year player.

As for Chisholm, he’s prepared for the roller-coaster the game provides. His homer Thursday broke a 15-day streak without a dinger, a period filled with too many weak ground balls. It is a hallmark of the game he chose that he might go days without making an impact, when instead of euro stepping over the plate he’s making an abrupt right turn back to the dugout.

He cannot control his fate in a manner that LeBron can or Kobe could, and if he’s given just one pitch to turn and burn on, he may very well miss it.

Chisholm knows this well and chooses not to dwell on it. Like the island kid who just knew he’d be a big leaguer some day, Chisholm may be right when he believes this game will reward his undying love for it.

“It’s not frustrating,” he says of failure, “because you know how hard the game is. It’s just like, ‘Man, I’m just praying I get another one. Give me another one.’ It’s not really like, ‘Man, I missed my only chance.’ No, because you still got two more strikes to play with. And you might get the worst swing of your life off, but it can be a hit.

“This game can really mess with your mind – because you could be hitting the ball as hard as you want every day and not get a hit. And then you can go break four bats in one day and have four hits. That’s why you have to just love it. Because even though it takes away, it gives back.

“And it gives back big.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Marlins' Jazz Chisholm lights it up as a rookie: 'You have to just love it'