Masters organisers plan revenge over bullish Bryson DeChambeau

For Bryson DeChambeau, the 2020 Masters quickly became the Schadenfreude Open as his tie for 34th – five places behind 63-year-old Bernhard Langer – fell so laughably short of his grand pronouncements. So, will it be a humbler, more circumspect American who shows up here this week? Erm, sort of.

“I was wrong to say that Augusta is a par 67 for me,” DeChambeau said. “It is a 68.”

As climb-downs go, this is not quite in the league of Goliath acknowledging that David was, as it turned out, not a cocky little lout with a dodgy catapult sponsorship, but, in fact, a fearsome warrior. And this not entirely committed retreat might lend his legion of detractors further ammunition only five months on from using that devastating social-media slingshot to fire DeChambeau’s words back at him.

Because Lee Westwood has already played a few practice rounds here this year and was stunned by the “firmest and fastest conditions I ever have encountered at Augusta”, and, with no rain forecast, the green jackets’ arduous stage has been set. “Put it this way,” Westwood told me on Thursday. “I don’t think they want 20 under to win.”

Of course, that was the record mark set by Dustin Johnson in that strange autumnal Masters when, in the eerie silence, the world No 1’s languid, unfettered stroll through the cathedral pines seemed so appropriate for the occasion. The organisers were not impressed, although whether their ire was raised by Johnson’s rout or DeChambeau’s rant is, intriguingly, a moot point.

“D J did what D J does, quietly and modestly crushing the field,” a Masters insider told The Sunday Telegraph. “The notable green jackets I spoke to were more riled by what DeChambeau said in the build-up. They felt he was mocking the National and a fast, firm and treacherous Masters could be their response.”

Typical DeChambeau. The man could unwittingly cause offence in a locked-up clubhouse. It is the great paradox of the 27-year-old that he is either the best thing to happen to golf in this burgeoning post-Tiger Woods era, or the worst thing ever to happen to it, period. Or, in some quarters, both; at the same time.

Andrew Coltart, the former Ryder Cup player and current analyst for Sky Sports, sums up the incongruity perfectly: “He’s turning golf into a one-dimensional, power-hitting game. There’s little doubt that watching Bryson over a traditional fairways and greens merchant such as Webb Simpson will attract more youngsters to the game. “It’s a similar situation to 30 years ago when John Daly appeared on the scene, hitting it miles and everyone going ‘wow!’ But, at the same time, that’s not what golf is all about, is it?”

But what is the game all about nowadays? As the game’s governing bodies, the R&A and US Golf Association, wrestle with this conundrum, teeing up a radical overhaul to put restrictions on equipment to rein in the biggest hitters, the biggest of them all carries on booming, making friends and enemies as he saunters through the wreckage.

Mark Chapman, the excellent BBC Radio 5 Live presenter, is certainly a fan, announcing on air last week that “in 20 years of doing this job, I don’t think I have ever interviewed anyone as fascinating as Bryson DeChambeau”.

In truth, the interview was standard DeChambeau, with his normal abnormalities and usual unusualness. At one point he compared himself to Thomas Edison and at another he claimed that he sometimes tried to drive the ball so far he almost blacked out (when Edison’s light bulb presumably comes in handy). Throughout, he depicted himself as the one-man revolution operating on a different plane, both technically and diligently, to his rivals.

“I want to give as much information to the world as possible, I’m not scared of that,” DeChambeau replied when asked about giving away his secrets. “I don’t feel like anybody’s going to work as hard as me, anyway, even if I do give them all away. If they work eight hours a day, I’ll work nine.”

It is obvious why a bullish, bragging comment such as this will wind up the locker room – Vijay Singh has been known to do nine hours on the range before breakfast – and when the tape recorders are turned off, a number of his Tour colleagues will point out that, as of yet, he has “only” one major to his name and has four ahead of him in the world rankings. The well-publicised coup might be in motion, but it has only just broached the king’s castle and the throne remains under lock and key.

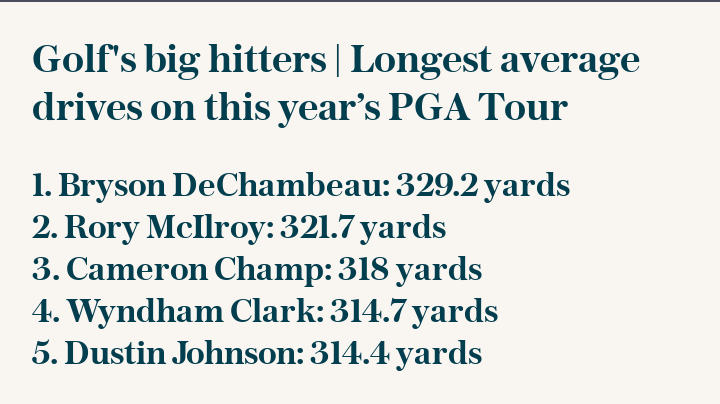

Yet his remarkable influence on the game should not be underestimated. Rory McIlroy admitted last month that DeChambeau’s performance in winning the US Open last September persuaded him to ramp up his action to achieve the 200mph ball speed and that, as a result, he introduced gremlins into a celebrated swing that Pete Cowen, his new coach, has been enlisted to rescue before Thursday’s first round.

This is hardly DeChambeau’s fault, but his part in ruining the sweetest motion in the game has nevertheless been added to a charge sheet the critics have ridiculously compiled. Everyone, they say, will eventually be sucked into “Moneyball Golf”, where analytics are all that matters and where “feel” and “touch” are mere memories in sepia.

Except there are some factors that the robots cannot account for in their algorithms and spreadsheets, and these are the bounce and the run of a fast and firm layout. Augusta is set to present the scientist with a wildly unpredictable challenge. In which playing to a par of 67, 68 or 72 could be a blessed irrelevance.