'There are many paths': Some NFL players find efficient ways to give back

The extraordinary success of the Justin J. Watt Foundation, founded in 2010 to provide athletics equipment and opportunities to middle school students, wouldn’t have been possible without “a lot of help from a lot of good people,” J.J. Watt said, and a heaping helping of humility.

The 2017 Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year knew he wanted to launch a nonprofit before he was drafted by the Houston Texans in 2011.

He turned to the Law and Entrepreneurship Clinic at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“I knew for a fact that I wasn’t smart enough to do it on my own,” Watt told The USA TODAY Network, “and I wanted to make sure we did it the right way, by the book, and they were incredible. I’m sure I could have spent hours and hours googling and understanding and reading the fine print of how it all works and trying to figure it out, but the truth of the matter is I had football, I had classes. Sometimes all you have to do is reach out and ask for help.”

A six-month investigation by The USA TODAY Network into how pro athletes engage in philanthropy, which included dozens of interviews and the review of thousands of pages of federal and state records of nonprofit organizations founded by Payton award winners, showed the NFL’s and NFLPA’s considerable promotion and celebration of their players’ community service and philanthropy do not match their efforts to educate players on nonprofit best practices and pitfalls.

The resulting knowledge gap, coupled with prestigious awards from the league and union that encourage players to give back, lead competitive young men to found nonprofit organizations that are often ineffective, award winners and nominees said. The learning curve is steep, including for those, like Watt, who seek expert guidance.

Watt’s mother, Connie Watt, who runs the JJ Watt Foundation out of her house, told The USA TODAY Network their first fundraising event in Pewaukee, Wisconsin, fell well short of expectations.

“The first year we did a 5K, we made $5,000,” Connie Watt said. “It was kind of my joke, we did a 5K and made 5K. That’s not the amount we wanted to raise, so we hired a marketing team and the next year we made $50,000. You’ve got to know when your skill set is not enough, and you need to bring somebody else in.”

The JJ Watt Foundation has since been ruthlessly efficient, reporting $51 million in revenue and $49.7 million in expenses through 2020, including $48.3 million — or 97 cents of every dollar spent — on charitable activities.

The totals are swollen by Watt’s viral Hurricane Harvey relief campaign in 2017, which began with a video posted to social media and an original goal to raise $200,000 through YouCaring.com. Watt chose the crowdsourcing platform because it only charges standard processing fees and asks donors for tips rather than collecting a large cut of donations.

It resulted in a $41.6 million torrent of generosity.

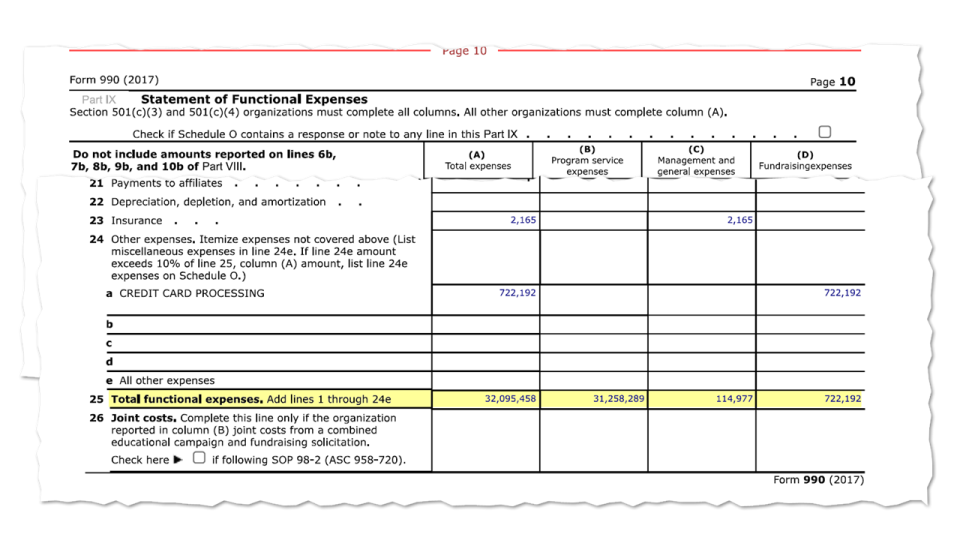

In 2017, the JJ Watt Foundation spent 97.3 cents of every dollar on charity.

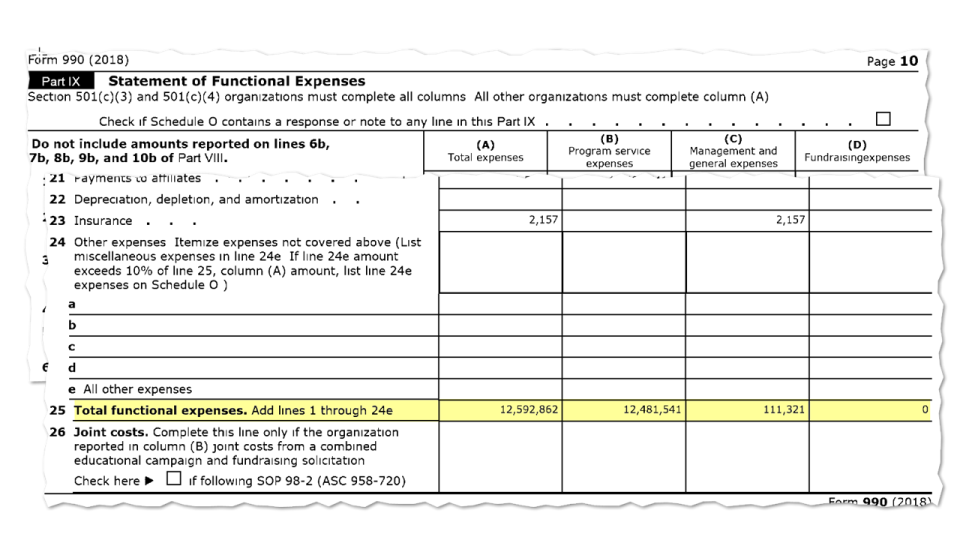

In 2018, it was 99.1 cents.

“That’s something I’ve been extremely adamant about, is the efficiency of making sure that every dollar donated goes as far as it can, especially with the hurricane relief,” said Watt, who retired from the NFL at the end of the Cardinals' season. “One, I’ve seen stories of other organizations doing it the wrong way, misusing funds, things like that. And two, people are trusting us with their hard-earned money and donations and that we’re going to do right by them and put it to use the right way.

“You have to really be laser-focused on maximizing the donations while minimizing the expenses. It’s hard work. You just have to be really committed to it and (have conviction) in what you’re trying to do.”

About the results?

Robert Ashcraft is the executive director of the Lodestar Center for Philanthropy and Nonprofit Innovation at Arizona State University. He teaches a class called “How to start a 501(c)(3).”

“Before you do anything, you do an environmental scan within your particular area of purpose,” Ashcraft said. “And it could be across anything. Food insecurity and solving hunger. Child development or after-school youth sports programs. Whatever it may be.

“What organizations are already deeply involved in that? Who is already in the space?”

It’s often far more efficient for professional athletes to use their fame and fortune to enhance the fundraising and social impact of an existing nonprofit, Ashcraft advised, rather than creating an organization that duplicates programs and services within a community.

Eli Manning, the former New York Giants quarterback and 2016 co-Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year, partnered with the Hackensack (N.J.) Meridian Health Foundation to launch the Tackle Kids Cancer initiative, which has raised more than $22 million in seven years, the hospital system confirmed.

Manning spends time with sick children, has donated millions of his own money and in 2021 joined the Hackensack Meridian Health Foundation board of trustees.

“There are many paths to take,” Manning wrote in an email to The USA TODAY Network, “but the most important is to give back in meaningful ways that have a true impact on people’s lives. You can chart your own path and launch your own charity, but remember it’s a steep learning curve. You want to make sure you have a clearly defined mission, winning strategies and the right people to execute your vision.”

The Larry Fitzgerald First Down Fund is not an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit but an extension of the Minneapolis Foundation, which manages more than $750 million in assets, administers more than 1,400 funds and spends better than 90 cents of every dollar on charity, according to its federal tax returns.

Fiscal sponsors report the financial activity of their managed funds in aggregate, which makes it impossible to glean an individual fund’s efficiency using public records.

“Generally, fiscal sponsors function like incubators for fledgling organizations until they complete the necessary paperwork to spin off into their own public charities,” said Laurie Styron, executive director at CharityWatch, noting it’s unusual for organizations with millions in annual revenue.

Fitzgerald said he chose a fiscal sponsorship over creating an independent 501(c)(3) on the advice of a financial adviser in 2005, during his second season in the NFL.

“My focus at that time was my work playing football, which is very much a full-time job,” Fitzgerald wrote in an email to The USA TODAY Network. “I did not want to try to also run or oversee a non-profit organization and I didn’t want to be involved in name only. A donor-advised fund provided a way for me to have my own charitable initiatives and make decisions about my charitable giving, without having to run an organization.”

Other examples of players finding ways to make it work:

— Calais Campbell won the 2019 Payton award after promoting and donating $20,000 apiece to Feeding Northeast Florida, the Clara White Mission, Wounded Warrior Project and the United Way, plus another $20,000 to Denver-area nonprofits.

“One of the most powerful things is connecting with people who already are doing the thing that you want to do and doing it well,” Campbell said. “Don’t reinvent the wheel.”

— Once Andrew Whitworth arrived in Los Angeles in 2017, he leaned on the Los Angeles Rams Foundation and its connections throughout Southern California to help identify regional areas of need. He began donating $20,000 after each home game to address homelessness in Louisiana and Los Angeles.

In 2020, the season Whitworth won the Payton award, he donated $215,000 to the Rams’ social justice fund and $250,000 to the Los Angeles Regional Food Bank.

“After a couple of years I decided, I’m just going to write my own checks, you know?” Whitworth said. “And I’ll raise money in every contract I sign. I’ll give a portion of it away. And that’s really when, honestly, I started making even more of a difference, because I stopped wasting my time just spinning my wheels.

“If we’re going waste our energy, then I want to spend that time going to a homeless encampment and making a difference. I want to go to Boys and Girls Clubs and spend time with kids. I want to create labs at schools. I got to a space where I finally realized the events were overrated and the actions are what I wanted to be part of.”

— From 2010-12, under the direction of Dionne Boldin during her husband’s three years with the Ravens, the Q81 Foundation eventually spent more than 90 cents of every dollar on charity.

“There was a lot of people that we had to fire and get rid of,” Anquan Boldin said. “And the older we got, the more we started to pay attention to what was going on, on the business side of it.”

“We just wanted the work that we were doing to be done right. We wanted it to be done in a way that was honest and fair,” Dionne Boldin said. “That’s the way all nonprofits should be run. Obviously, that isn’t the case.”

In 2014, the couple pledged $1 million to create an endowment at a second nonprofit, The Anquan and Dionne Boldin Scholarship Fund. He was named the 2015 Walter Payton Man of the Year.

In 2017, Anquan Boldin co-founded the Players Coalition, a nonprofit with a mission to improve social justice and racial equality.

“Anybody that wants advice or has questions about anything pertaining to not-for-profits, the Coalition would be more than willing the help,” Boldin said. “We’re all about helping guys in any way that we could. I know a lot of times when guys are fresh in the league, guys are reluctant to reach out, especially if they don’t know that person personally. But I encourage guys to use the resources.

“The NFL is a community, whether it’s guys from the ’70s or guys that have just gotten into the league. From what I’ve experienced, the majority of the people want to help each other. It’s like a brotherhood.”

“The questions would be: ‘What are the results we seek and how do we organize in such a way to get there? How do I use my celebrity as a professional athlete? How do I motivate others to contribute?’” Ashcraft said. “And if I’m about the results, a nonprofit might be the last thing I would ever create.”

Similar resources exist throughout the country

Lisa Dancsok is the chief brand and impact officer at the Arizona Community Foundation, home of the Jerry Colangelo Center for Sports Philanthropy, which aims to simplify foundation management by offering fiscal sponsorships.

Athletes can open an account with the foundation and use its 501(c)(3) status to raise tax-exempt donations. This costs a small fee, which is far more efficient than founding a nonprofit and ensures legal compliance and donations ending up where they are intended.

“We have six to eight professional athletes — most of them have retired — that have funds with us,” Dancsok said, “and we work with them to define what their philanthropic giving should be. And we make it easy, because we do all the work for them, for less than 1%.

“We are a nonprofit and our interest is in giving to the community and working on behalf of the community, so we keep our fees down very, very low, and we do that because we can. Community foundations have been around for 120 years, and ours for 45 years, so we’ve figured out how to do this the right way, and I think that’s the message that I would want to get across: No matter where you’re at as an athlete, look at your community foundation as an option.”

NFL Foundation endorses fiscal sponsors

In mid-January, a month after being contacted by The USA TODAY Network, the NFL Foundation distributed its annual grant application for players’ nonprofits, using the league’s teams as an intermediary to players’ representatives.

“As you know, there are many challenges and pitfalls with starting and managing a nonprofit foundation, not to mention the increased scrutiny from media and others on nonprofits managed by professional athletes and entertainers,” the email read.

The league’s four-page tip sheet on starting a nonprofit was attached as a PDF.

The message closed with a warning about the high fees of some nonprofit management companies.

“While we are not in the business of endorsing third parties,” it read, “and typically recommend that those starting off in this space consult with a community foundation or donor-advised fund, the NFL Foundation did want to bring two organizations to your attention as potential resources as they seem to operate in the best interest of players and Legends while not charging exorbitant fees.”

It provided links to The Players’ Philanthropy Fund, founded by former Ravens kicker Matt Stover, and The Giving Back Fund, both nonprofits that offer fiscal sponsorships geared toward athletes and celebrities.

The message also stated that “The Giving Back Fund also has created Foundation Fundamentals — a partnership with the NFLPA to provide NFL players with philanthropy consulting tools, resources and best practices as well as consultations at no cost to help players with their philanthropic needs.”

Damar Hamlin ‘donations’ not tax deductible

Two weeks earlier, the NFL faced the prospect of a player dying on the field when Bills safety Damar Hamlin went into cardiac arrest and collapsed during a game against the Bengals on "Monday Night Football."

Medics rushed to save the 24-year-old’s life before a horrified national TV audience, an experience so traumatic the game was never resumed.

Far down the list of concerns that night: Nearly $8.7 million poured into a 2-year-old GoFundMe account Hamlin had started in college with the hopes of raising $2,500 for his “Chasing M’s Foundation Community Toy Drive.”

Another generous young man, living his dream, looking to give back.

But Hamlin had never received federal 501(c)(3) status, public records show, and the GoFundMe he created was tied to Chasing Millions LLC, which houses his for-profit clothing brand.

This, unbeknownst to donors, has become a quandary: None of the donations are tax-deductible, according to Andrew Morton, a partner at Handler Thayer LLP and chair of the firm’s sports and entertainment philanthropy group.

Morton is legal counsel for The Giving Back Fund, which in recent weeks has granted the Chasing M’s Foundation a fiscal sponsorship but has yet to collect the money from GoFundMe as the parties work through the issue.

“Nobody made a charitable contribution,” Morton said, “despite the fact that it said Chasing M’s Foundation, despite the fact that GoFundMe says ‘donate.’ … People who gave $10 or $20, no big deal. But people gave tens of thousands of dollars. And I promise you, the people who gave tens of thousands of dollars did not consider that it might not be charitable.”

The GoFundMe has surpassed $9 million from nearly 250,000 donors.

The NFLPA named Hamlin its Week 18 Community MVP and a finalist for the Alan Page award, which come with $10,000 and $100,000 donations, respectively.

On the night Hamlin collapsed on the field in Cincinnati, a video from his inaugural toy drive at his mother’s daycare center went viral, along with the GoFundMe.

“I’m thankful that I can even be in this position to give back,” Hamlin said in the recording. “I can’t really remember too many people got in front of me to show me, ‘This is the way to go. This is the way to do it.’”

Last week, Hamlin began to use his newfound fame to encourage fans to learn CPR and donate to the American Heart Association.

Years earlier, he was filmed greeting children, signing autographs and handing out toys.

“He’s working hard in the community, giving back already,” a friend said in the closing shot. “He’s a person that’s a future Man of the Year in the NFL. Surely.”

Jason Wolf is a sports enterprise and investigative reporter for The Arizona Republic. Reach him at jason.wolf@gannett.com and follow him on Twitter at @JasonWolf.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: NFL Man of the Year: Some players find efficient ways to give back