The man who threw 115 MPH: Legendary flame-thrower made his biggest mark playing in Elmira

Professional baseball's history in Elmira is filled with stories and characters.

Don Zimmer got married at home plate at Elmira's Dunn Field. Earl Weaver, who married an Elmiran, honed his fiery major league tirades as manager of the Elmira Pioneers. Hall of Famers such as Jim Palmer and Wade Boggs sharpened their skills as young pros in Elmira.

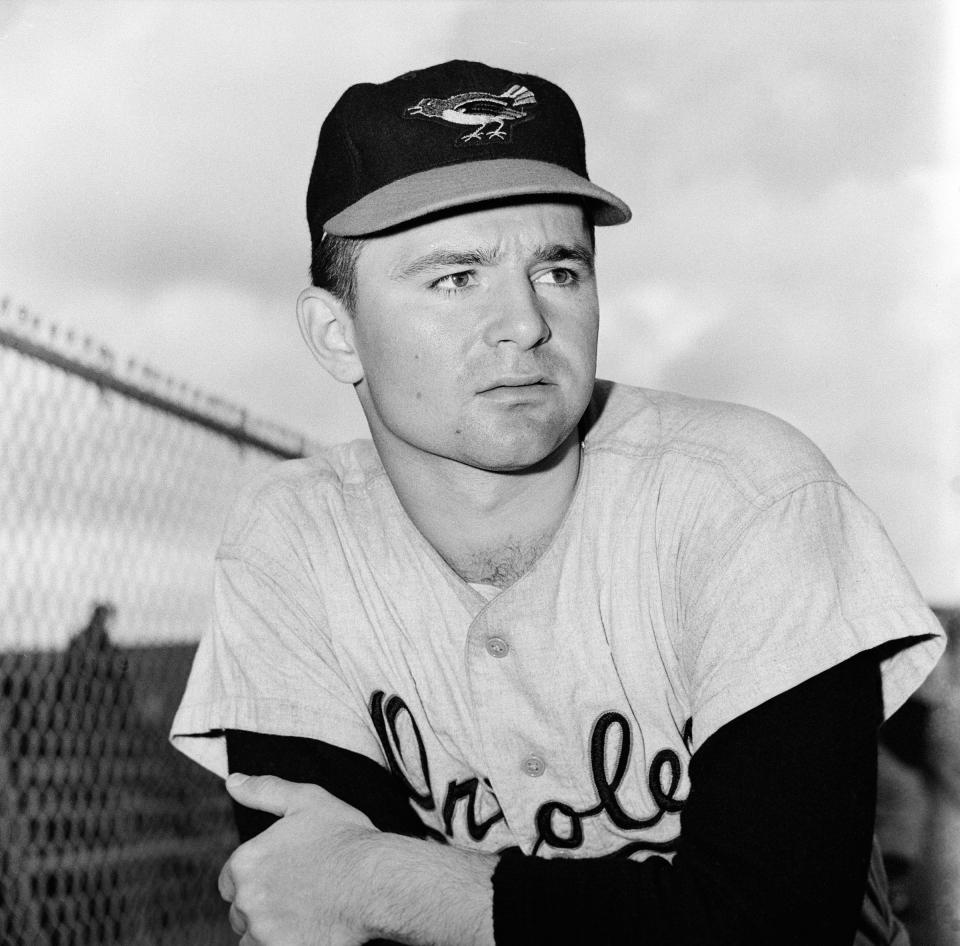

At the top of the Elmira baseball chronicles sits Steve Dalkowski, a native of New Britain, Connecticut, best known for his near-mythical fastball and as the inspiration for eccentric hurler Ebby Calvin "Nuke" LaLoosh in the 1988 film "Bull Durham," as played by Tim Robbins.

Dalkowski died from COVID complications in April of 2020 at age 80 while in a nursing home. His talent and battles with alcoholism are chronicled in the book, "Dalko: The Untold Story of Baseball's Fastest Pitcher," written by William A. Dembski, Alex Thomas and Brian Vikander.

Beyond unfulfilled promise and personal struggles was a guy whose pitching velocity astonished some of baseball's biggest names and thrilled fans in Elmira, where he produced his best stretch of baseball for the upstart Eastern League champion Pioneers in 1962 at age 23.

Pat Cain, Dalkowski's younger sister, said the interest in her brother's life and career still surprises her.

Said Cain, who lives in Middletown, Connecticut: "It's been all these years and Stevie's gone, but I still meet people and I'll say I'm a Polish girl from New Britain. 'Oh, did you know Steve Dalkowski? As a matter of fact I did.' It's still quite amazing."

He remains an impactful pitching presence in large part because of the work of Don R. Mueller, a retired physics professor known as "The Nutty Professor of Sports" for his calculations and analysis in the sports world.

Mueller has broken down the key to Dalkowski's velocity and shared it with the likes of Rob Semerano, who at 42 still holds onto a big-league dream in part by following Dalkowski's pitching approach.

"At 42 I can throw the ball in the mid to upper 90s," Semerano said. "I've actually been clocked over 100 once and pretty much can throw every single day. My arm feels great every single day."

Part of Elmira's comeback kids

The Elmira Pioneers captured four Eastern League championships from 1937 to 1943, joined the New York-Penn League in 1957, then returned to the the Eastern League in 1962 as Class A affiliate of the Baltimore Orioles.

With Weaver guiding the club, the Pioneers opened with a 22-32 record before winning 50 of their final 86 games. Elmira beat York in the playoff semifinals and topped Williamsport, three games to one, for the league title.

Two pitchers from that team went on to great success at the big-league level, albeit in different capacities.

Dave McNally, 15-11 for the Pioneers that year, became a stalwart in the Orioles' rotation and won 184 major-league games with a 3.24 ERA, helping Baltimore win the World Series in 1966 and 1970.

Pat Gillick struck out 16 for Elmira in an 8-0 win over York to wrap up that '62 semifinal series. Arm issues cut short his playing career, but he became one of the most successful general managers in major-league history and was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2011.

Andy Etchebarren was Elmira's catcher and went on to success at the big-league level over 15 seasons, twice being named to the all-star team as a member of the Orioles. Mark Belanger was another notable name from that group.

"Weren't they great? Every one of them," Weaver said after Elmira won the title.

More: 'Buzzie' an Elmira icon and Ernie Davis' best friend: How he spread the 'Express' legend

Hometown heroes

Robert "Skip" Valois, a retired professor of public health whose career included 29 years at the University of South Carolina in Columbia, was a boy growing up Elmira in the 1960s who "lived at the ballpark" for multiple summers.

Recollections include watching Weaver pick up third base during a tantrum. The umpires had to agree to let Weaver sit in the stands after he was ejected so Weaver would give back the base to allow play to continue.

"I'm a Southside kid, so I could ride my bike to Dunn Field," Valois recalled. "I just had to be home when the street lights came on or have permission to be at the game with friends and older kids from the neighborhood.

"We're kids coming up learning how to play and when you've got what you think is big-time professional baseball in your blue-collar, gray steal town, you go see these guys."

More: Ed Sobkowski: Reflecting on the life of an Elmira football legend you might not know

Fans took notice of Dalkowski

The 5-foot-11, 175-pound Dalkowski stood out for reasons beyond his thick glasses. The sound of the southpaw's fastball still echoes with Valois.

"I remember Dalkowski's ball made a sound that was different and when it hit Andy Etchebarren's glove or (John) Mason's glove or whoever was catching, it was something to hear," Valois said.

The turnaround of the '62 Pioneers largely coincided with Dalkowski's surge. After early struggles saw him allow 19 runs and 31 walks in the first 21 ⅔ innings that season, Dalkowski had a stretch of 56 innings in which he gave up 26 hits and two earned runs, striking out 67 and walking 28.

When asked at the time what changed, he responded, "I wish I knew," while sharing some insight.

"I think I'm throwing the same, but I'm not pumping as hard as I used to. Maybe that's good," Dalkowski said.

Dalkowski had been in the Orioles' farm system since he was an 18-year-old in 1957 and never had an ERA below 5.14, largely because of his wildness. He finished his 1962 season in Elmira with a 7-10 record, a 3.04 ERA and 192 strikeouts in 160 innings.

Said Orioles scout Barney Lutz that year: "You just can't believe he's the same pitcher we've been watching for six seasons in the organization."

Myth vs. reality

Nolan Ryan's fastball was clocked at 100.9 mph in 1974, a time in which radar readings were measured near the plate instead of out of the hand. Some calculate the same pitch would be clocked at 108 mph using modern radar techniques.

Actual velocity remains an unknown given the lack of radar guns at the time, but Weaver said Dalkowski threw harder than Ryan or anyone else he had seen. Ted Williams, Paul Blair and Cal Ripken Sr. are among those on record marveling at Dalkowski's velocity. Numbers from 110 to 115 mph have been thrown out there.

Sam McDowell delivered the forward to the book "Dalko" and said Dalkowski threw the fastest pitch he had ever seen.

"If you were close it was a hissing sound that was louder than the other pitchers and the pop in the glove was definitely different than the other pitchers," Valois said.

Marty Chalk, who in 1968 became public address announcer for the Pioneers, tended bar at Rustic Gardens in Pine City in the early 1960s. He saw Dalkowski there frequently as a customer and also witnessed his talent on the mound as a fan.

"The only thing I remember about him is obviously he threw so hard," Chalk said. "He kind of reminds me of Ron Guidry, very thin. I used to think to myself, 'Where the hell does it come from?' And it was all in the arm.

"He had no secondary pitches. He couldn't throw a curveball to save his life. Everything was a fastball and it was all over the place at the time."

Chalk said if Dalkowski had a pitching coach like players have today he could have been an outstanding major-league pitcher. The fact that his best year as a pitcher came with the future Hall of Famer Weaver as manager was likely not a coincidence.

With hopes of making the Orioles' major-league team in 1963, Dalkowski suffered an elbow injury during spring training that sidelined him until the summer and impacted him the rest of his career. Stories vary on whether he got hurt on a pitch or throw to first on a bunt.

"He was fitted for his uniform for the majors in the morning," Cain said. "He was pitching for the Yankees in the afternoon and Boog Powell, who was playing first base, said he heard the pop."

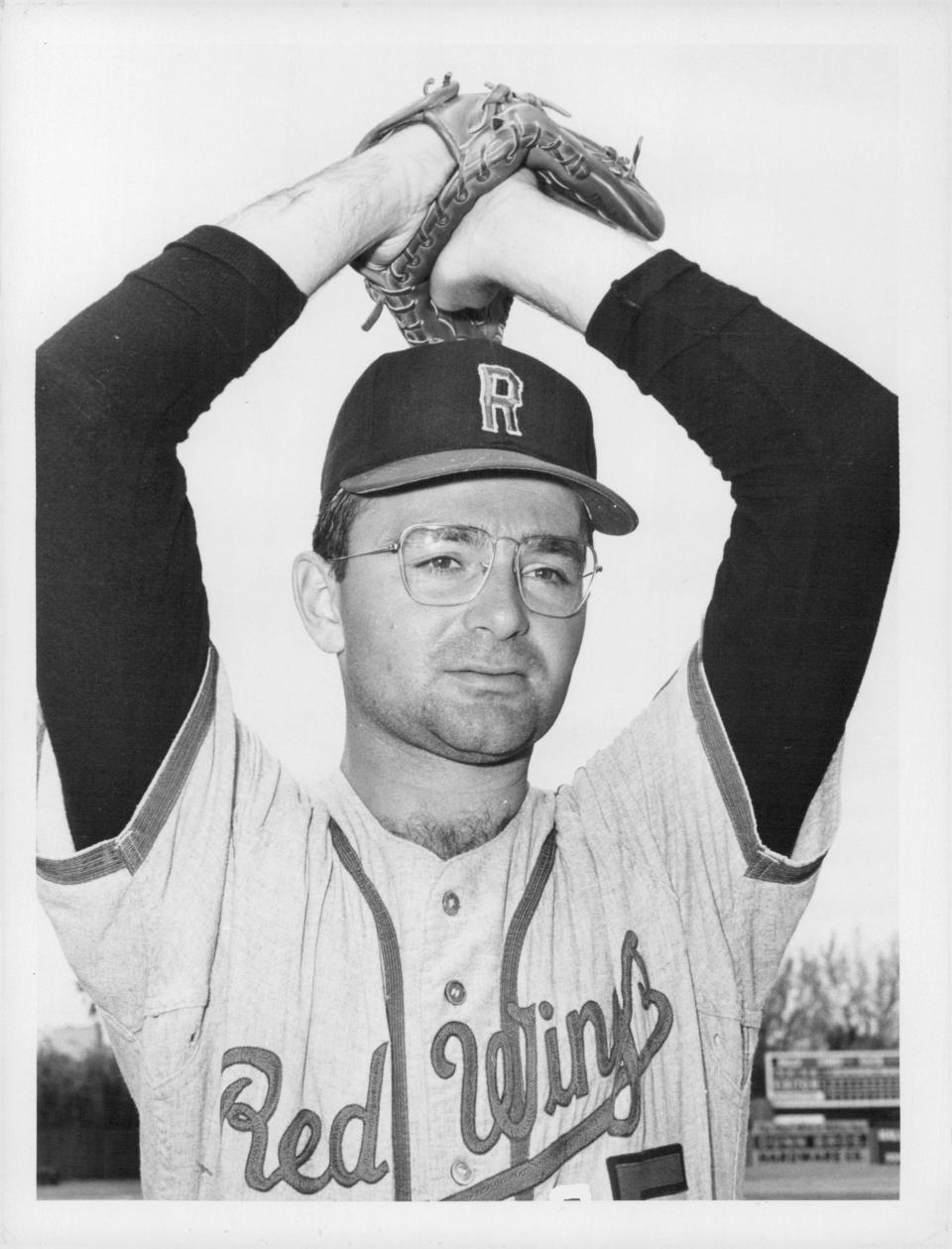

Dalkowski split time between Rochester and Elmira that year and pitched only 41 innings. With his velocity down and the control he gained in '62 gone, Dalkowski pitched for Elmira and two other minor league teams in 1964 before his final year of pro baseball in 1965.

'It wasn't in the cards'

Dalkowski spent the last 26 years of his life in a nursing home with what his sister described as dementia caused by alcoholism. He remained close to family and would frequently join his sister at New Britain Rock Cats games, where he invariably would be pointed out by the PA announcer despite his best efforts to go unnoticed.

Unless around former teammates, such as close friend Ray Youngdahl, Dalkowski rarely talked about his playing days. Cain said her brother did mention how much he admired Weaver.

"Stevie became very quiet about his baseball career," Cain said. "I think it was a real big disappointment. He obviously wanted to do better, but it wasn't in the cards. But he made a lot of friends."

A favorite story shared by Powell after Dalkowski threw out the first pitch for an Orioles game involved Powell carrying a tipsy Dalkowski as a coach came around the corner during spring training.

"Boog threw Stevie in the pricker bush. We all cracked right up because when Boog told the story it was the first time I heard it," Cain said. "Being his sister, I'm like, 'Oh my God, did he get hurt?' He said, 'Patty, of course he got hurt, what do you think? We had to pull all those prickers out of him.' "

More: From the archives: Caton's Deacon White had long journey to National Baseball Hall of Fame

Dalkowski's pitching legacy

Mueller has applied physics to hit a tennis ball more than 140 miles per hour and to teach others to throw a baseball harder. He was signed by Blair to play in the Empire State Baseball League in 1987 and has showcased his work in other sports.

When it comes to the slender-built Dalkowski, it's the wrist action Mueller looks at as it translates to pitching.

"Stretch the forearm and contract the top. That’s the kind of hyper-mobility Dalkowski had," Mueller said. "So when the wrist goes layback, you’re storing energy as the forearm goes layback and then as the elbow pulls forward I call that a leverage factor, then the forearm fires forward and the wrist fires forward and that’s where you have the catapult-like effect and you can generate 100 mile an hour speeds."

Semerano pitched professionally in the Yankees, Astros and A's organizations from 2004 to 2009 before undergoing Tommy John surgery in 2009 to repair a ligament tear in his elbow. He returned to professional baseball for a season in 2014 with the Camden Riversharks of the Atlantic League.

He has remained in shape, right arm included. A strong lower body boosts his velocity, but he adds, "That final whip to be able to pull down on the laces to really propel it is where the final piece of the puzzle comes in."

Semerano met Mueller through his dad's physical therapist after his dad had double knee replacements.

"He's got some cool insights into how to create more velocity, how to create more whip with your arm and basically applying laws of physics to throwing a baseball," Semerano said.

"With the neutral wrist, that’s definitely helped. Your arm just feels like a whip. I also feel like I come out of the gate ready to throw pretty firm. Doesn’t take me too long to warm up. Other things about using the body and different laws of physics. A lot of it was stuff I had kind of done, but sometimes when you find out the reason why you’re doing it you can do it with more intent. I think that’s helped as well."

Semerano was invited by the Yankees to pitch in exhibition games against the Japanese national team in 2018, with his fastball reaching 95 or 96 mph as he approached age 37.

Semerano owns and operates the Big League Talent baseball academy in New Jersey with his dad, Bob, a former minor-leaguer who played in the New York-Penn League against the likes of Elmira's Boggs. The chance to play in the big leagues is still on Semerano's mind, with age the biggest obstacle in teams giving him a shot. There has been interest from some pro teams, particularly after CBS Sports profiled Semerano this year.

He remains interested in the right opportunity to balance making a living with having a legitimate chance to reach the majors. Most likely that would be as a reliever, with his ability to recover quickly from day-to-day a selling point.

"I know a lot of people are kind of amazed when they hear I’m still trying at 42, but I don’t really see it as trying as much as I’m kind of running my race and if a big league team were to come calling, obviously I’d be ecstatic and I’d sign in a heartbeat, but I do it because I love it," Semerano said. "It’s my release, it’s my way of relaxing and there’s no drug on the planet that could make me feel as good as throwing a baseball does."

Follow Andrew Legare on Twitter: @SGAndrewLegare. You can also reach him at alegare@gannett.com. To get unlimited access to the latest news, please subscribe or activate your digital account today

This article originally appeared on Elmira Star-Gazette: The life and impact of baseball legend Steve Dalkowski