MJ’s greatest strength? He understood what fans wanted

For the 1997-98 Chicago Bulls, much like the 2018-19 Golden State Warriors, victory was both an aspiration and an obstacle.

In the wake of the coronavirus pandemic pausing sports, ESPN pushed up the release date of “The Last Dance” — the highly anticipated documentary about Michael Jordan’s final season as a Bull — to Sunday. The hype has coincided with the release of “The Victory Machine” by Ethan Sherwood Strauss, a Warriors scribe for The Athletic who examined the rise and fall of the dynasty through Golden State’s final season with Kevin Durant.

The similarities struck me. Striving for a three-peat, they were weighed down by the trappings of success: battles over who deserves credit, looming free agency, the threat of a breakup.

Both teams were proxies for their eras. Twenty-one years after Jordan’s final title, the Warriors undid the story he sold. The book (which you should pick up) dismantles the idea rooted at the core of selling sports: that winning solves everything, or at least provides a long, meaningful relief commensurate to the sacrifices required for achievement at the highest level — in short, that winning is worth dealing with all the other stuff that comes with it. The Warriors were publicly miserable. They squabbled on the court. With each other. With referees. Coach Steve Kerr and Durant engaged in a news conference proxy war over, unironically, the team’s philosophical quest for joyful basketball.

I imagine “The Last Dance,” which features a season’s worth of exclusive tapes, will include snippets of skin-crawling ruthlessness and pettiness that’ll make you wonder about how many burner accounts Jordan would have today. There’s a side to Jordan we really only saw in his Hall of Fame speech and Wright Thompson’s 2013 ESPN profile: an intense man without a muse, still keeping score, taking mental notes, unsatisfied, gnawing. I imagine we’ll like it.

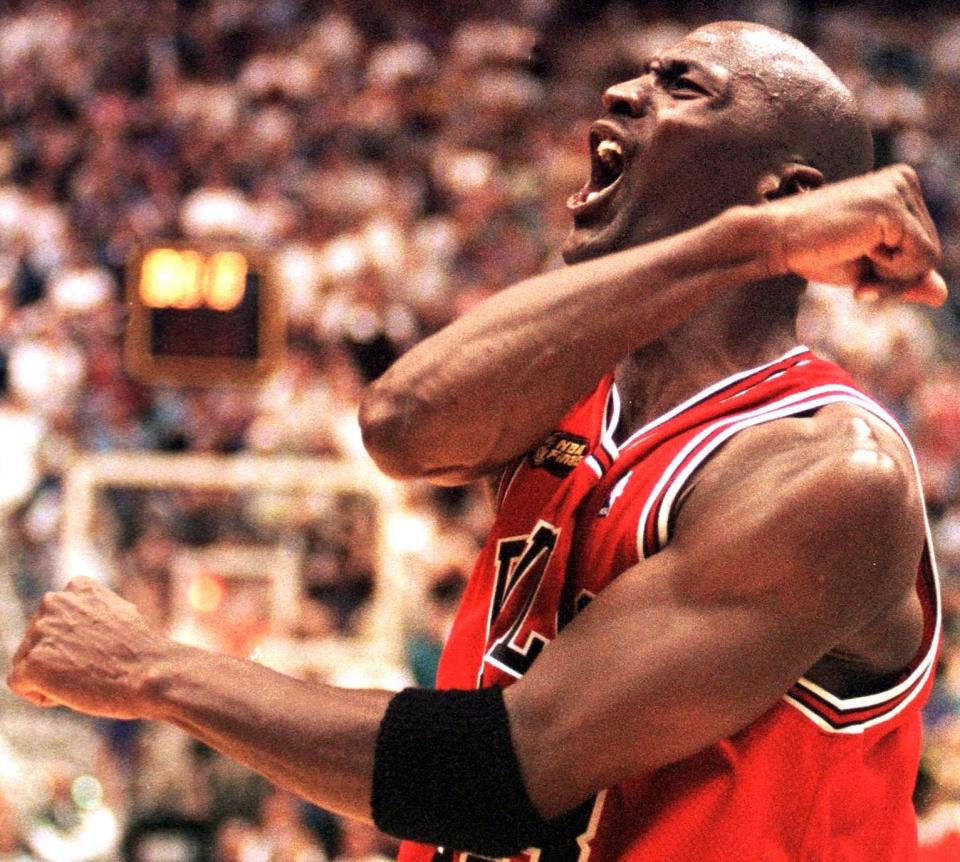

We’ve always liked it, because through the gossip and the fist-fights and the screaming and the power struggles, Jordan’s winning smile — worth countless fans and endorsements during his career — always shined through. Whether victory left him resplendent or depleted, it looked like it fulfilled him. He did what the modern athlete no longer does: He seemed happy.

I don’t know if he was, but for his purposes, perception was reality.

He always understood that, and he was willing to go to the lengths modern athletes won’t to show he was in it for the right reasons — the right reasons being what appealed to fans. Despite making more off endorsements than he did from playing for the Bulls, he never betrayed that business was more important than basketball.

He didn’t short-change sponsors, either. According to David Halberstam in “Playing for Keeps,” Jordan — at 35 years old in 1997, coming off two straight championship runs and despite a toe infection — went to Paris to play in a preseason tournament sponsored by McDonald’s, even though his two top teammates, Scottie Pippen and Dennis Rodman, weren’t playing.

Halberstam also wrote that Bulls owner Jerry Reinsdorf knew his best leverage against Jordan in contract negotiations was Jordan’s fear that holding out too long for a contract would paint him as just another spoiled athlete.

Jordan was affable with reporters, his public image mediated by Nike, Spike Lee, Sports Illustrated and “Space Jam.” There’s no proof he actually uttered the phrase, “Republicans buy shoes, too,” but he was decidedly unpolitical. He never changed teams (until he did). He made you think he wanted to kill his opponents. In fact, it was only at Kobe Bryant’s memorial that the public found out about their friendship. It made for a better story if we thought they weren’t close.

Above all, Jordan smiled from his perch. He showed you how good it felt to win.

Take it all together and what we have is a man willing to supplicate his personality completely in service of a persona that existed wholly for marketing the game and his own image. He turned himself into a vessel for the viewers' hopes, selling an easy, uncomplicated story of success that vibed with the country’s ethos: of deliverance, fulfillment, transformation through unbridled work. Jordan packaged the American Dream back to the middle class. He was a great player, probably the greatest in NBA history. He was also a mythological character, playing out a story that reflected the values of the zeitgeist.

The modern NBA star shatters that myth. Led by LeBron James, he takes the long and winding road from city to city, searching for fulfillment beyond mere championships. His fans follow him. His relationship with the public is somehow both highly mediated and oversaturated.

And he doesn’t pretend to be happy when he’s not. He doesn’t sell the dream. He’s only tangentially responsible for the financial health of the league, so he’s not really sweating his likability. He piles up money, all the while undercutting the capitalist underpinnings of sports. Take Durant, who admitted winning a title didn’t fill the void he expected it would. At the MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference on March 1, 2019, NBA commissioner Adam Silver blew the lid off the top of the NBA’s burgeoning mental health discussion by revealing a chunk of the players he corresponds with are truly unhappy.

Players are part of a larger demographic of young people disproportionately affected by mental health issues — a group that is looking at the world they were promised, pondering why it isn’t quite enough and venturing out for self-actualization, for the perfect fit. There’s no guarantee that the search will bear fruit, but opaque positivity simply wouldn’t suffice in an age of routinized self-improvement. It’s hard to sell a dream that isn’t yours. Jordan was the face of a public that valorized capitalism. Modern superstars represent our ambivalence.

More from Yahoo Sports: