Lessons from Kansas City: Be less like Mike, more like Evander

When BYU tips off Thursday against Duquesne in the NCAA Tournament, there is no secret what the Dukes’ game plan will be — get physical with the Cougars. BYU doesn’t like it and it doesn’t respond well when teams do it.

The Cougars are a squad that thrives on cuts to the basket and 3-point shots. The catalyst is their movement away from the ball. When the offense is clicking, it’s nearly unstoppable, as tournament teams Kansas, Iowa State, Baylor, Texas, TCU, San Diego State and NC State can attest.

The teams who manage to disrupt the offensive flow disrupt the Cougars. Texas Tech provided a case study during its 81-67 quarterfinal win at the Big 12 Tournament in Kansas City. The Red Raiders led from start to finish and built a lead as high as 23 points.

“I think we were physical early off the ball,” Red Raiders coach Grant McCasland said during his halftime interview on ESPN. “(BYU’s) freedom of movement, if they can get into the paint with their cuts, it really opens up the 3. I thought we were physical enough off the ball to keep that from happening.”

Translation: Bully the Cougars physically and you can take them out mentally. Easy to say, but harder to do, as BYU’s 23-10 record indicates; however, while not every team can pull it off, in March, there are more who can.

Texas Tech punched the Cougars in the mouth from the opening tip. The Red Raiders attacked the basket with reckless abandon. On defense, they pushed, they shoved, they used their elbows, shoulders and knees to break BYU’s will. None of it was dirty. All of it was by design.

As a result, the Cougars’ reliable sharpshooters were sped up just enough to misfire. It didn’t matter if they were being guarded or left wide open. What mattered is they had been knocked out of rhythm. BYU made just seven of 35 3-point shots and surrendered 33 defensive rebounds.

Historically in the NCAA Tournament, the physicality of the game has often dictated BYU’s success, and except for Jimmer Fredette’s Sweet 16 run in 2011, the Cougars have been left with a black eye and an early departure over the last 40 years.

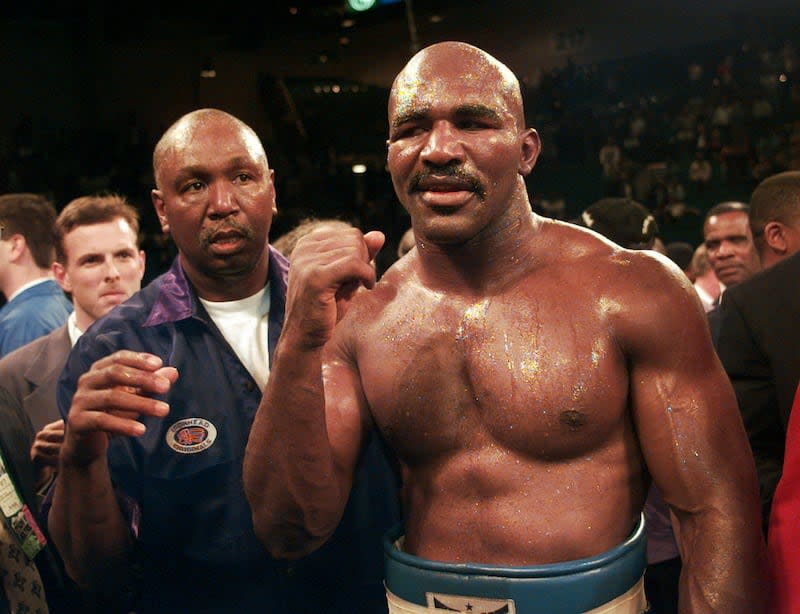

If Duquesne (24-11) comes out and tries to go “Mike Tyson” on BYU and bully them into the ropes, there is another sports case study the Cougars can glean from — Evander Holyfield.

When the two boxers first fought in Las Vegas on Nov. 9, 1996, Tyson was the reigning WBA heavyweight champion and a 5-to-1 favorite. He thrived on physical and emotional intimidation and bullied his way around the ring.

Holyfield knew what he was up against. He also knew that he had the skills to beat him, so long as he didn’t get away from his game plan. Tyson’s early fury and flurry of punches would often cause his opponents to panic. It sped them up and made them vulnerable to mistakes. That’s typically when he knocked them out.

On this night, the challenger refused to let Tyson turn his strengths into weakness. When the champ landed a punch, with his fists or his forearms, Holyfield would answer. When Tyson would push, shove, head butt and hold, Holyfield did the same. He showed no fear.

As the 11th round arrived, Tyson was tired and Holyfield was focused. The bully plan hadn’t worked, and it was the most feared man on the planet who was left physically and emotionally vulnerable — and Holyfield took him out.

The 1997 rematch ended in Tyson’s disqualification when his bully plan failed again.

When the bullies come for BYU this week in the NCAA Tournament, and they will, the Cougars can lean on the fearlessness of Holyfield. He couldn’t be intimidated, no matter how hard Tyson tried to push him around. Holyfield’s mental edge made all the difference, and in the end, it gave him the physical push he needed to finish him off.

BYU needs only to look in the mirror. It is the No. 1 scoring and rebounding team in a conference that landed eight teams in the NCAA Tournament. The Cougars are experienced and have the firepower to terminate the season of any opponent they play, so long as they stick to their guns and operate at their own pace.

The marching order for Thursday and beyond is to be less like Mike and more like Evander, to enter the ring as a fighter who knows who he is and what he wants and is determined not to be denied.

Be the team who, while being challenged physically at times, can keep its emotional edge, and stay in the game — come what may. After all, like boxing, much of March Madness is a head game and the Cougars have the wits to win and advance so long as they keep their focus.

Holyfield’s tale does carry a caution worth listening to. When a bully runs out of gas and is on the brink of defeat, sometimes they lash out — and go for the ears.