Karate, patience and pain on a trip to its roots in Japan's Okinawa

Excelling at karate starts with your outfit.

You need to tie the loops of your suit correctly - not easy for a beginner.

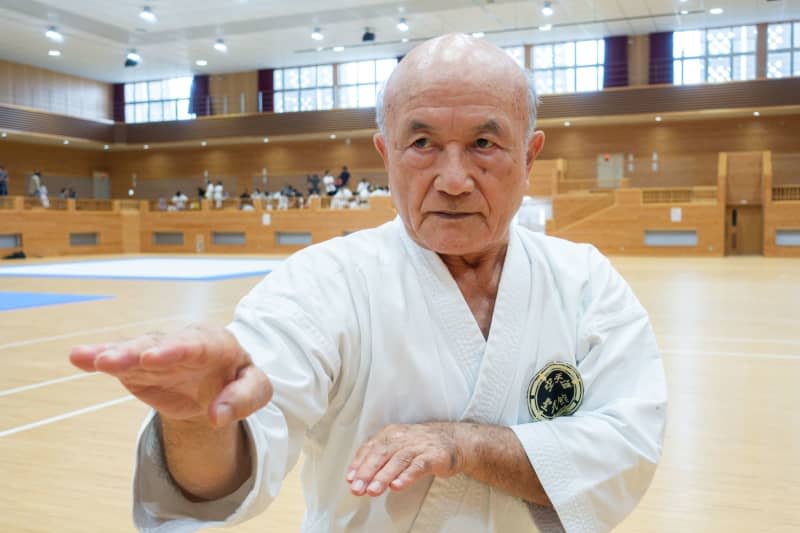

Terumitsu Taira helps learners out until the snow-white suit no longer slips.

We move over to the lawn of the Okinawa Karate Kaikan training and museum complex where Taira set up two cement blocks and laid a layer of roof tiles over the space between them.

The tiles are not made of clay, but of hard plastic that can be broken and reassembled.

But they are just as hard as clay tiles, he says, before donning gloves and demonstrating his skill.

Taira steps in front of the block, tenses his body, takes a swing and splits four in a single stroke.

He performs this act of strength without a primal scream, or even any sound at all.

It is my turn next.

I am right-handed and am reluctant to risk my writing hand so opt to sacrifice my left instead. And decide to take on not four tiles but one.

Then, I break it in two, a proud beginning to my forray into the original home of karate.

"Karate originated here in Okinawa centuries ago," says Yasushi Nakamura, a spectator on the lawn. He runs the modern karate centre, located on the island of Okinawa not far from the city of Naha.

Nakamura, now in his early 60s, has been practising karate since the age of five.

Traditional Okinawa karate is nothing like sports karate, he says. Here, the focus is on uniformly strengthening the body and mind, exemplified in the exercise called kata.

It's made up of fixed sequences of movements in a defensive fight against an imaginary opponent.

"I feel completely clear after a training session," says Nakamura, strolling through the karate museum in steel sandals, the shoes worn by early karateka to strengthen their muscles.

Although undocumented, Okinawa has always had its own art of self-defence, called Ti.

Later, it was influenced by practices from other parts of Asia, when the island world of Okinawa formed the independent kingdom of Ryūkyū (1429-1879).

That gave rise to karate, now practised by some 130 million people worldwide, the museum says.

Karate became an Olympic sport in Tokyo in 2021 and Ryō Kiyuna won the gold medal in the kata discipline.

He comes from Okinawa and occasionally drops by for training here at the centre, where you can fortify yourself with Okinawa soba noodle soup in the restaurant. It's topped with seaweed shaped like a black belt.

Actual people wearing black belts meanwhile stand waiting in the training hall for the next session.

One is Zenpo Shimabukuro, 79, who holds the highest master's degree, and his son Zenei, 35.

I learn from them that the basic and breathing techniques are one thing, but the next is looking into the soul. For both, karate is part of their way of life, expressing humility and appreciation.

"There is no first attack in karate, only defence," says Zenei, an electrician by day. "Karate is not there to fight, but to be able to protect the people I love."

His father Zenpo, who still works as an estate agent, adds, "We don't have winners or losers. It's like shadow boxing."

That's why you can do it on your own.

Zenpo and Zenei show me hand and foot positions in a crash course and remind me to bend my knees and use my hips. They are tireless in their corrections of my posture.

In Japan, patience is a core value and high virtue.

"Imagine an opponent attacking you and you are now defending yourself," says Zenei.

I move my hands back and forth and learn to move one forward while keeping the other close to my body to achieve more speed and effectiveness.

It uses muscles I never knew existed. I know they'll hurt tomorrow morning.

Suddenly, Zenpo encourages me to knock his arm aside. He holds it diagonally above my head.

I try and am amazed and in pain. He may be in his late seventies but his arm feels like pure iron.

We end as we began, by bowing to each other. "Karate is always characterized by respect," says Zenpo.

I ask him something that's been puzzling me all the while. To me, Japanese people seem cordial, peace-loving and not at all aggressive. There may be traffic, but no one honks their horn. People don't shove, jostle or swear in public. Japan has a low crime rate and seems like a safe place to be.

So why would you ever need karate?

Father and son mull on that for a while.

Zenei weighs in, finally.

"I'm training my mind and body and I feel that it's keeping me healthy. But my goal is to never have to use karate until I die."