The future of offensive football

Football is a never-ending game of adjustments and cycles. For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

Last week the people at Hudl put together their “Hudl Blitz,” a virtual clinic that assembled some of the smartest minds in the game to talk about the things that they do well. You could hear Charles Davis and Kirk Cousins talk about breaking down game film, or Steve Sarkisian outline how he installs and runs run/pass options (RPOs) from Saturdays to Sundays, along with countless other clinics and programs designed to inform the viewer.

One of the smartest parts of the week was a roundtable on defense at the high school level, moderated by Chris Vasseur. Vasseur, known to many as Coach Vass, is the mind behind the Make Defense Great Again podcast, along with the Run Vass Option podcast, which focuses on the defensive side of the football.

During this roundtable, Vasseur and other defensive coordinators at the high-school level started with this premise: How do they handle the RPO (run-pass option) game in what they do? They had a number of answers — some of which we will get to in a moment — but the undercurrent of each of them was this:

Force opposing offenses to run the ball.

Remember, this is the high-school level we are talking about, where the running game is often thought of as king. But these defensive coordinators want to make the choice for the offense on each and every play: Make the QB turn around and hand the football off, becoming a spectator. Or better yet, make him keep the football himself. Both of those are preferable to the quarterback pulling the football away from the running back at the mesh point and hurling it in the air.

Why? Because the passing game, even at the high school level, is more efficient. Numbers back that up, especially in the NFL. Offenses are more efficient — and as such more productive — when they put the football in the air.

Thanks to the smart people who run the website rbsdm.com (yes, that is short for “Running Backs Don’t Matter”), we can chart this out a bit. This graphic below looks at expected points added (EPA) per play both in the running game, and the passing game:

Up and to the right is where you want to be. Down and to the left? That is not where you want to be.

*Glares at Adam Gase.*

Diving into these numbers a bit, the top five offenses during this time in terms of EPA/play are as follows: The Kansas City Chiefs, the Green Bay Packers, the Baltimore Ravens, the Tennessee Titans, and the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. Kansas City checks in with an EPA/play of 0.171, followed by the Packers at 0.145, the Ravens at 0.134, the Titans at 0.124 and the Buccaneers at 0.079. You also see that the two most-recent Super Bowl champions are among the top five.

Now, we can break these out in terms of passing plays versus running plays. For example, the Chiefs had an EPA/dropback of 0.273 over these past two seasons. When they run the ball? An EPA/run of -0.046. Green Bay? The Packers posted an EPA/dropback of 0.145, and an EPA/run of -0.014. As a matter of fact, during this period only two teams in the entire NFL posted a positive EPA/run: The Ravens (0.082) and the Titans (0.020). That’s right, the two teams many believe are the best at running the football are the only teams to post a positive EPA/play when they did so. Every other team was negative, starting with the Arizona Cardinals at -0.001 on down to the worst in the NFL, the Pittsburgh Steelers at -0.202.

In fact, the worst passing team by this metric was the New York Jets, checking in at -0.136 per dropback. That was still better than their EPA/run of -0.181. Every single team posted a better EPA when they threw the football, opposed to when they ran it.

Passing is more efficient, which is why defenses are trying do do everything they can to force offenses to run the football.

Forcing the Run

(Denny Medley-USA TODAY Sports)

So, the question becomes for defensive coordinators: If you want the offense to run the football because passing is more efficient, how do you force the QB to hand the football off?

A good starting point for this might be in the Big 12. The conference gets mocked for “not playing defense,” but that could not be further from the truth. Some of what you are seeing trickle into the NFL in terms of defensive concepts comes from the Big 12, often after working its way up from the high school level, because after all if you want to know what the future of football looks like in all three phases, you had best start there.

One of the ways teams have tried to force the offense to hand the football off is by playing light in the box. That brings us to Ames, Iowa. The Iowa State Cyclones are one of the defenses at the front lines of handling the spread/RPO game at the college level, and led by defensive coordinator Jon Heacock, they have found a means:

The 3-3-5 defense.

This is something that many have written about, and back in the summer of 2019, I dove into this defense at length, finding parallels between what Heacock was doing on Saturdays in the Big 12 and what Bill Belichick was doing on Sundays in the AFC East. The premise is this: play light up front with three safeties in your 3-3-5, but trust your overhang players and a hybrid safety to still get into your fits against the run:

That might look crazy, but there is a method to the madness. As Cody Alexander — one of the smartest football minds on defense out there — described it:

The box literally has nine players involved in the fit. By using a safety from depth (JS), the defense is ensuring it has an extra fitter in the box and most likely unblocked. What the Cyclones have done is squeeze everything into one gap in the middle of the formation. If anything bounces, it is cleaned up by a trapping CB to the boundary or the Sam LB patrolling the edge of the box to the field. Against the run, the trapping CB from the field can even make his way into the fit depending on how the offense uses the two WRs.

Here’s what that looks like on film:

You can play light up front, but once you bring the overhang players, as well as that hybrid “joker” safety into the run fit, you can stop the run. Show quarterback a light box pre-snap, make him hand the football off and become a spectator post-snap, and then get into your fits against the run.

Sure, sometimes the offense might break off a big play, but as we have seen from the above EPA numbers, you are better off as a defense over time turning the offense into a run-first team.

This is something Bill Belichick has incorporated over time, and every single time I think of how to stop explosive passing offenses I return to this idea.

There are the Patriots a few seasons ago, facing the explosive Kansas City offense and using a 3-3-5 look down on the goal line to force Patrick Mahomes to become a spectator.

Of course, this is just one way that defenses are perhaps trying to force the running play. Another was touched upon recently by Pro Football Focus; Seth Galina, who is another brilliant mind covering the game. Galina looked at the rise of two-high defensive structures this season in a recent piece for PFF. Titled “Why two-high defenses are poised to take over the NFL,” Galina argues that the Vic Fangio/Brandon Staley defensive structures are the next big thing:

In all, 48.6% of all early-down snaps were played with that middle-of-the-field closed look, down from 53.9% in 2018 and 57.6% in 2019. And the important thing to know about these numbers is who is pulling the average down under 50%.

The Los Angeles Rams led the NFL in expected points added (EPA) allowed per play this regular season and played the fewest early-down pre-snap closed looks — only 11% of their early-down snaps were in a pre-snap closed look. For reference, the 2015 Seahawks did this 75% of the time.

Of course, some teams played a low percentage of snaps in this look before the 2020 Rams came along, but the schemes that spread throughout the league are the ones that dominate statistically. That’s what the Rams did in 2020 with new defensive coordinator Brandon Staley, who landed a head-coaching job with the Los Angeles Chargers after just one year of coordinator experience.

Staley previously coached under Vic Fangio in Denver and Chicago. And for what it’s worth, Fangio’s 2020 Broncos recorded the second-lowest pre-snap middle-of-the-field-closed rate in the league. Back in Chicago, the Bears hired Sean Desai as defensive coordinator this offseason, and Desai has worked with both Fangio and Staley.

Now remember, it was Fangio’s defense back in Chicago that perhaps foreshadowed the fall of Sean McVay/Jared Goff. Fangio’s structure — using Quarters coverage, ignoring pre-snap motion — led to the defenses that slowed down the Los Angeles Rams back in 2018, culminating in Belichick and the Patriots emerging victorious in Super Bowl LIII. Rather than try and bang his head against the wall, McVay did the next best thing: Hire Staley, who worked under Fangio in Chicago.

But the rise of this two-high looks pre-snap is a means of forcing the offense into that decision to run the football. With both safeties deep, the offense is usually “plus-one” in the box, meaning they have the advantage if they keep the ball on the ground. But it is a fool’s choice. Over time — as the EPA numbers tell us — the defense wins when the QB hands the ball off.

Of course, you still need to stop the run from this look, and defenses have ways of doing that. One means is by doing something called “slinging the fits,” which is a concept that Kyle Cogan, a high school defensive coordinator/head coach, has discussed at length both on Twitter and in various podcasts and coaching clinics. The premise is this: If you operate out of a two-high defense, you need to get one of your outside linebackers/overhang defenders into the run fit somehow, otherwise you are going to be out-manned up front.

So. you do what Cogan terms “sling the fits.” If you are one of those two outside players and the quarterback looks at you on an RPO play, you drop and play the pass. If the quarterback is looking away from you, you get yourself into the run fit:

Had more run fit questions.

First example is 2 high and needing to sling the fits (between S, M, W) if trying to be gapped out, without having enough guys.

Second is one high and being gapped out.

Third is blitz coverage where you are always +1 in the fit, even vs qb run plays pic.twitter.com/wylrhhQkYk

— Kyle Cogan (@CoachCogan) July 27, 2019

As you can see in that first example, the defense is in two-high before the snap but in order to get one of the SAM or the WILL into the run fit, you need to “sling the fits.” So if the QB turns away from you, you get into the fit. After all, it would take a damn good quarterback to look one way and throw the other…

…which is where this conversation might be headed.

Slinging it backside against two-high

(Mark J. Rebilas-USA TODAY Sports)

So, let’s play along with these defenses. They’re going to show offenses these two-high looks and force us to run the football, hoping we take the bait. These defenses will stay light up front, keep two safeties deep and hope to be in position to break on throws if we are stubborn enough to throw against these designs.

Let’s craft some ways to throw against these designs.

Take this play from the Pittsburgh Steelers last season, which could be a good starting point. They’re squaring off with Fangio and the Denver Broncos, one of the main drivers behind this discussion. Sure enough, Denver shows a light box and two-deep safeties pre-snap for this play. Ben Roethlisberger takes the snap and shows run action — turning to his left first — before snapping his eyes backside to throw a speed out on the right against the Quarters coverage:

You can almost start to wonder if the Broncos were indeed “slinging the fits” here. They have two overhang defenders — one flexed out into the slot and the other widened a bit over the wing tight end. That defender sees Roethlisberger turn away from him and sides down — perhaps as Cogan would coach him to do — but in this instance, it creates space for Roethlisberger to attack on this backside speed out.

Here is another example of this kind of look in action, from the Chiefs this past season against the Saints. Patrick Mahomes carries out a mesh with his running back by turning to his left — with the defense in a two-high look before the snap — before snapping back to the other side of the field and throwing the hitch route to the boundary against a cornerback playing off-coverage in Quarters:

Spinning back against these looks and attacking away from the side the quarterback opens up to creates opportunities for the offense. However, we’re showing examples of two NFL quarterbacks, both of whom are likely going to end up in Canton. And let’s face it, Mahomes is an alien. More often than not, you see quarterbacks simply throw to the side they open to on these designs, and with good reason. It takes guts for a quarterback to open to one side and simply throw to the backside, because that player is assuming that things are going to be favorable when his eyes flash backside. And what’s the old adage about making assumptions, both in football and life?

Yeah, not something you want to do often.

So we’ll need to turn to other route designs to attack these two-high schemes.

Slinging it deep against two-high

Jake Roth-USA TODAY Sports

We’ve talked briefly about how to attack two-high looks by attacking away from where the quarterback flashes his eyes on RPO designs, but not every quarterback is a future Hall-of-Famer. So let’s look at other designs that are more universal.

There is one universal answer for how to attack defenses in football today, almost regardless of coverage: Just run four verticals on every play. Why? Because that route concept does have an answer for almost every coverage. There is a reason that every coaching clinic on the defense side of the football takes about five minutes before diving into how to defend verticals: Offenses run it because it works. Let’s face it, if Wesleyan University was running it back in the late 90s, it works.

But everyone’s favorite offensive play — next to Y-Throwback/Leak of course — might need a talented quarterback to execute it. Especially against these Cover 2 looks, if you are going to throw that hole shot to the outside. That’s a tough throw. The “scholarship” throw if you will, to borrow a term from new Minnesota Vikings defensive backs coach Karl Scott.

Yet four verticals will be part of both the present, and the future, of football. With good reason.

That is not the only answer in the passing game to these designs, of course, and as much as every offensive coordinator wants to call it on every down, you have to have other clubs in the bag. That leads us to the realm of the “Quarters beaters.” Because try as you might, if defenses are going to drop into Cover 4 you’ll want to have other designs to dial up.

That brings us to “Pout,” or post/out. One of my personal favorites to run against Cover 4, and something that leads us to Provo, and Zach Wilson.

Say what you want about Wilson and his draft stock, but one of the concepts that he executes at a very high level is this combination which can be deadly against Cover 4. Here is what that looks like drawn up:

The outside receiver runs the post route, while the inside receiver runs the deep out. The beauty of this design against Cover 4 is that the cornerback, playing with outside leverage, has to cover the post route while the safety, playing with inside leverage, has to cover the out route. This varies from team-to-team, but based on the defensive coverage rules once the inside receiver becomes “vertical,” the safety is responsible for that route, even if he breaks to the outside. As an offense, you get the leverage advantage on both routes.

Which leads to plays like this:

North Alabama drops into Cover-6, or Quarter-Quarter-Half, on this play, playing the Quarters or Cover – look over the post/out route combination. Both the out route and the post are open, and Wilson takes the deep shot for a huge gain.

Of course, when you think about offense today — and perhaps the future of offense — your mind might start to wander in the direction of Myrtle Beach. Why? Because of the Coastal Carolina Chanticleers. This past season their offense perhaps opened some eyes to what can be done conceptually on the offensive side of the ball, and recently Ted Nguyen of The Athletic provided a comprehensive breakdown of the various elements in their offensive attack.

As Willy Korn, their co-offensive coordinator, put it to Nguyen:

It’s a 21 personnel (two running backs, one tight end, two receivers), spread-option offense,” Coastal Carolina co-offensive coordinator Willy Korn explained. “We’re going to get into a bunch of different formations and have a bunch of different motions and shifts and different presentations but run a lot of the same core concepts over and over and just try to window dress them the best we can. At the end of the day, it’s option football, option concepts but not in the traditional sense.

Perhaps anticipating some of these coverage looks we have talked about, Korn and the Chanticleers have some answers for Quarters when the ball goes in the air. Take this example against, of all teams, BYU:

You can see Coastal Carolina’s offense and this 21 personnel package at work here. But on this snap, the Chanticleers take to the air, and attack BYU with a post/curl combination. It works much the same as the post/out combination against the Cover-4 side of the field on this play. The corner route operates against the safety who is playing with inside leverage, while the curl route works against a cornerback who has no help over the top. Quarterback Grayson McCall throws the curl, but both routes are open.

Another route concept that is great to dial up against these two-high coverage shells is sometimes termed “989,” with a vertical route to each side of the field with a post route in the middle. A distant cousin of four verticals, the reason this design works against two-high looks is two-fold. You have the post route in the middle of the field with the potential to split the safeties, as well as the vertical routes on the outside. If the defense stays in Cover 2 and the safeties condense the throwing window on the post, the bold and daring quarterbacks can throw the hole shots to the outside.

Wilson and BYU opened their game against Houston this past season by running 989, as you can see drawn up here against the pre-snap two-high look:

As this play unfolds, Wilson carries out a mesh with his running back in the backfield and looks deep. Houston drops into Cover 4 and the two safeties — after one drops down initially in response to the run look — take away the post. So Wilson takes the deep shot:

It’s not exactly the “hole shot” against Cover-2, but you get the effect. Wilson takes the deep shot, his receiver makes the play at the catch point, and the offense has a big play against one of these two-high looks pre-snap.

Of course, just because the defense shows two-high before the snap does not mean they will stay in that once the play begins. So you need to be ready for that. We’ll dive into slinging it against the rotations next.

Slinging it against the rotations

(Jasen Vinlove-USA TODAY Sports)

As Galina outlined in his piece on the growth of two-high defenses in the NFL, Quarters coverage could be how these teams handle the passing game on the back end. But as we just uncovered, there are ways to attack Cover 4 in the passing game, which could lead to defenses showing the offense Quarters/two-high before the snap and then spinning into something after the play begins, hoping to bait the quarterback into a mistake:

Quarters could be an answer. After all, we saw the Tampa Bay Buccaneers eliminate the potent Kansas City Chiefs offense by playing quarters variants in Super Bowl 55. Last season, we also saw the highest number of quarters-coverage snaps against passing plays since we began charting in 2014. So, it’s an excellent place to start.

The other answer is staying in a two-high look long enough and then spinning a safety down after the snap as a robber but still playing either Cover 1 or Cover 3. These types of coverages give the defense layers.

If a defense plays Cover 1 and rushes only four players, there will be a free “rat” player looking to eliminate difficult routes.

That leads to a perfect example, highlighted by Galina, of the Dolphins spinning from two-high into a single-high look and spooking Jimmy Garoppolo, leading to an interception:

Smart offenses will need to anticipate such rotations from the defense and have a better Plan B than “have your quarterback spin wildly into throwing a vertical late in the down with a free safety reading his eyes.” Or, maybe, a better Plan B than Garoppolo at quarterback, but that is a discussion for another time.

One such answer? Things we have already covered in whole or in part. If the defense wants to show two-high before the play and then spin into single-high, attacking on the outside with hitch routes or speed-out routes are a reasonable response. Why? Because the cornerback has no deep help and has to respect the vertical stem, so hitch routes and speed-outs are a great way to attack cornerbacks who are afraid to get beat deep.

Another way is with four verticals. Yes, everyone’s favorite concept. But if the defense is willing to spin into single-high at the snap, then those inside vertical routes up the seam are perfect for the offense. That gives the QB the ability to manipulate the single safety to one of the seam routes, and throw to the other.

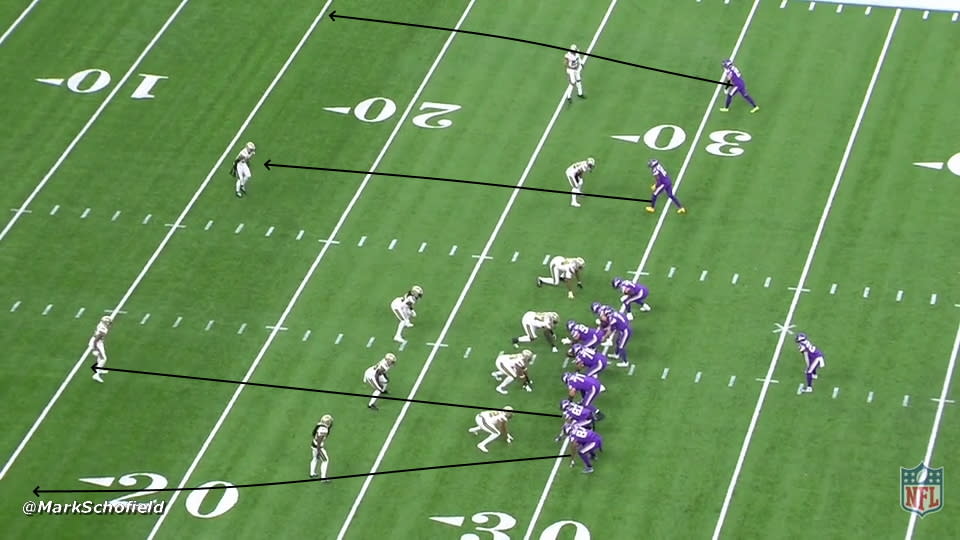

Take this example from Kirk Cousins and the Vikings, against the Saints. Before the play, the defense shows Cousins two-high safeties, and the Vikings are going to run four verticals:

But just because New Orleans shows two-high does not mean they are staying in it, and the Saints spin their safeties at the snap:

Cousins reads that and does exactly what was outlined above, looking first to his tight ends on the left before flashing his eyes to the right to hit rookie Justin Jefferson for a big gain:

From the end zone angle you get a glimpse of Cousins first looking on the left, before coming back to the right to hit his rookie receiver.

Beyond four verticals, another design previously discussed offers a solution when the defense rotates to single-high. That solution is Pout, the post/out combination. Only this time, the out route might be the quarterback’s best friend. Take this example from Wilson and BYU, as he has to react to that post-snap rotation from two-high into single-high against, of all teams, Coastal Carolina. Here is the look before the play:

You can see the Chanticleers lined up with two safeties deep before the play. Only as we have alluded to, they will spin this into a single-high safety look at the snap:

Now watch as this comes together:

This should be the closing argument, right? Because not only do you have a play that works against Quarters coverage providing a solution when the defense spins into single-high, but do you see what Wilson does on this play? He carries out the fake with his running back to one side of the field before spinning back to the right to throw the out. This holds the safety who is dropping down in place, allowing the out route to come open.

Were it not for the holding penalty on this play that negates the catch-and-run touchdown, this would be like the movie “PCU,” where the character Pigman — who is writing his senior thesis on the “Caine-Hackman Theory,” which is the notion that at any point in time a movie starring either Michael Caine or Gene Hackman is on television — sees “A Bridge too Far” come on TV, a movie starring both actors. This is the closing argument.

Only there is one more thing to ponder, perhaps the answer that has been staring us in the face the whole time. The way offenses might eventually counter what defenses are trying to do against them.

Run the damn ball

(Photo by Mike Ehrmann/Getty Images)

That’s right, run the damn ball.

Having spent countless hours and over 4,000 words outlining how defenses are going to attack these two-high safety looks in the passing game, perhaps the answer has been staring us in the face the whole time. If defense are going to play the numbers, force teams to run the football and craft coverages behind them that are going to require the quarterback to flip his eyes full-field or hit on shot plays downfield, maybe offenses should not play along.

Maybe they should run the ball after all.

Again, the numbers tell us this is not the answer. This entire piece began with numbers outlining how for every single NFL team over the past two years, even the worst passing games are still more effective throwing rather than running. Furthermore, the league’s two-best rushing attacks — Baltimore and Tennessee — are the only two teams with a positive EPA/rush over that period. Every other team, including the past two Super Bowl champions, has a negative EPA/rush. Every. Single. One.

Perhaps this is lunacy, but there is something to consider. Think of how we began, with the idea that if you have two-deep safeties before the play as a defense, you have to do something to counter-act the fact that you are outmanned/outgapped up front against the run. Remember the Kyle Cogan “slinging the fits” discussion? To get the run fits in place from a two-high look the defense has to do something with the overhang defenders.

But what if you could still put the numbers in your favor as an offense?

In the AFC Wild-Card game between the Indianapolis Colts and the Buffalo Bills, the Bills had to try and find a way to be more efficient when they ran the football. During the regular season, Buffalo produced an EPA/rush of just -0.082. The Colts, known for playing with a lot of two-high looks, were more than content in trying to force Josh Allen to be a spectator.

What is one thing the Bills tried?

Not letting Allen be a spectator.

Allen was Buffalo’s leading rusher on the day, carrying the ball 11 times for 54 yards and a touchdown. Take this play, from Buffalo’s drive before halftime:

The Colts have their two safeties deep and show a light box. So what does Brian Daboll dial up? A quarterback draw. The play goes for 16 yards and a fresh set of downs, and would end up being the biggest running play of the game for the Bills offense.

Buffalo would not only get the win, but they would finish the day with an EPA/rush of -0.047. Still…not great! But better than they had been doing during the regular season.

Of course, as an NFL offense you do not want your very expensive quarterback to take on the wear-and-tear of a running back. But if defenses are going to lighten the box, keep two safeties deep, and dare you to run, then the answer — or at least an occasional answer — might be to play along. How? By running the football with your quarterback and really playing the numbers advantage. If defenses are doing to play with five (or even fewer, as we highlighted with some of the Iowa State designs from earlier) in the box, then turn +1 into +2 as an offense and design running plays with your quarterback as a complement to what you are doing offensively.

If nothing else, as an offense you might take some of the ownership back and instead of the defense forcing what you do as an offense, maybe you start to dictate the terms of the play back to them. To do that, however, you might need a quarterback with some mobility. That brings us to the debate over whether such a trait is a prerequisite in today’s NFL, and in incoming rookies. That…that is a debate that we can leave for another time, but you probably know where I stand on that issue.

Who knows? Maybe, just maybe, we will get to a place where running backs matter again. Because given the copycat nature of the NFL, teams will start copying what the Staleys and the Fangios of the world are doing, and everyone will be showing two-high pre-snap and hoping that offenses hand the ball off. That might even lead to more teams going lighter and faster on defense. And as we know, football is a cyclical game, and every action leads to an equal reaction. Coastal Carolina’s 21 personnel option game might be featured on Sundays before you know it…

What have we learned, Charlie Brown?

This past weekend marked the launch of Paramount+, yet another streaming service to add to your growing list of content outlets. As any well-adjusted, middle-aged man would do, the launch of Paramount+ led to me catching up with a movie I loved as a kid: “Bon Voyage Charlie Brown! (And Don’t Come Back).”

The premise of this movie is that Charlie Brown and a few of his friends, including Linus van Pelt and of course his beloved dog Snoopy, travel to France as exchange students. Along the way hijinks ensue, such as Snoopy playing tennis at Wimbledon — where he is apparently a member in “good standing” — Snoopy renting a car in France, Snoopy slugging root beers in a bar…basically a lot of Snoopy getting into mischief.

The creators of the movie, including Charles M. Schultz, left the ending somewhat open-ended. To allow for a potential sequel or other content. In 1983 that was realized with a prime-time event that aired that Memorial Day. In that network special Charlie Brown tells his sister Sally about what happened after the events of the movie, as the group traveled home. With stops at Omaha Beach and others, Linus educated the young children about events of World War II and World War I.

The title? “What Have We Learned, Charlie Brown?”

In that spirit, what have we learned today, other than I like to make random references when writing?

Well, we learned that defensive coordinators from Friday nights to Monday nights, and all the days and nights in-between, are trying to force offenses to run the football. Why? Because the numbers have told us that the passing game is much more efficient, particularly when viewed through the lens of EPA. When even the worst passing games are still better off when they throw the ball, you know that passing is — and might remain — king.

As such, defenses are using a variety of means to force the offense to run the football, and turn the quarterback into a spectator. Teams are using 3-3-5 looks and playing with light boxes. They are also showing two-high safety looks before the snap and giving the offense the advantage up front, daring them to run the ball. Sure they might “sling the fits” as Kyle Cogan describes it, or do some other things post-snap as outlined by Seth Galina, but the premise is the same: Make them run.

So offenses, as they always do, will adjust. We’ve walked through a variety of ways that teams might attack in the passing game, from trying to throw backside on RPOs — away from the direction the quarterback opens in case the defense is trying to game the QB — to attacking downfield in a few different ways. Of course, as an offense you’ll want a Plan B built into those designs, in case the defense does spin the safeties at the snap, but you can still be effective downfield in the passing game.

Provided you have a good quarterback. Perhaps this clash of schemes is the undercurrent to the current QB carousel.

But then there is this idea: Maybe these offenses should in fact take the bait? Maybe, just maybe, they should run the ball. If the defenses are going to play light up front, maybe exploit the numbers advantage after all…and go all in by relying on the QB as a runner, to really make the most of your advantage up front. Especially if teams are going to adapt on defense by going lighter and more athletic to cover the receivers and tight ends that offenses are using and trying to target in space.

In a fast and small world, perhaps strong and big becomes king.

After all, what we might have learned is really that football is indeed that cyclical game, and the schematic reaction to the current action is about to be upon us. Maybe not this season, or the season after, but some day the running game might just be king again.