England players nearly joined rugby rebel league in 1995

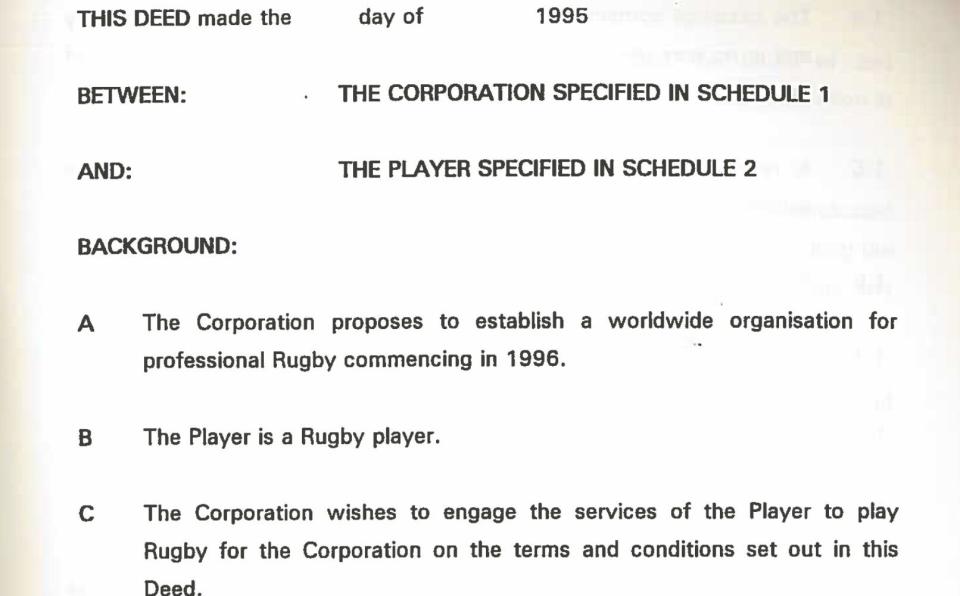

It has been locked away in a safe for almost 30 years but the original player contract for the ‘World Rugby Corporation,’ the £200 million rugby circus that threatened a global breakaway, can now be revealed.

The document, which remains in pristine condition, serves as a stark – and fascinating – reminder of the ‘rugby war’ that could have brought more than 120 years of Test rugby to an end.

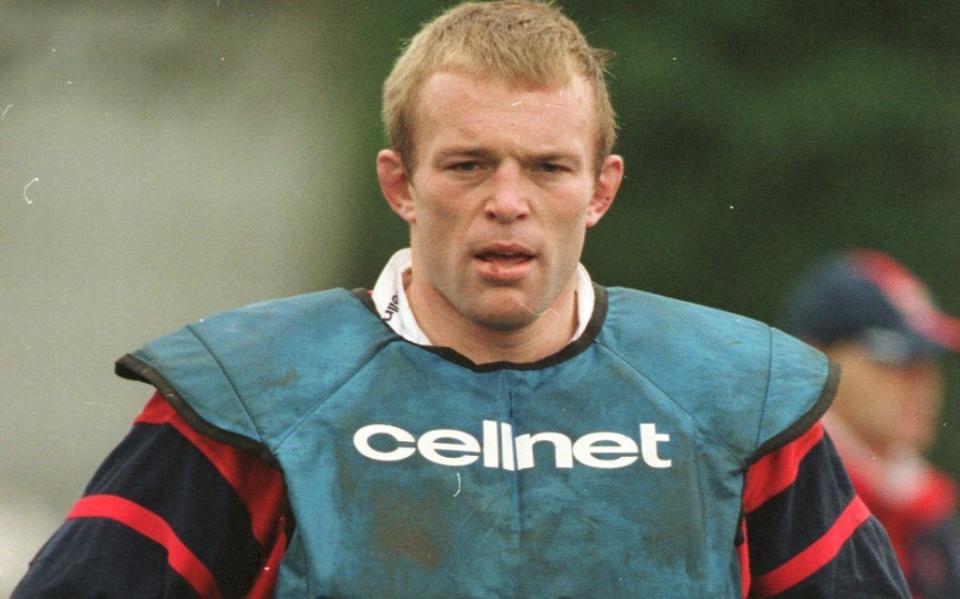

And, according to the owner, former England and British and Irish Lions lock Martin Bayfield, a moment of missed opportunity for the Rugby Football Union, the consequences of which are still felt today, with the union on the verge of offering new hybrid contracts to gain greater control of their players.

The battle for the future of rugby union as it stumbled into professionalism against the backdrop of the 1995 World Cup in South Africa was fought predominantly in the southern hemisphere as media moguls Rupert Murdoch and Kerry Packer went head-to-head in a race to secure broadcasting rights that would fast-track the end of the amateur game.

Murdoch looked to have landed the decisive blow when on the eve of the World Cup final between the Springboks and New Zealand, it was announced that the three main southern hemisphere unions – South Africa, New Zealand, and Australia, had agreed a US$550 million deal with his News Corp organisation.

The 10-year agreement gave News Corp exclusive television rights to a new annual Tri-Nations international tournament, a Super 12 club competition and all inbound Test tours to the three countries.

But News Corp, and indeed the unions, did not know at the time that behind the scenes, the leading players in each of the three countries had already been secretly approached by the representatives of the World Rugby Corporation (WRC), which was fronted by former Wallaby prop Ross Turnbull and latterly backed by Packer.

Around 400 players had signed provisional contracts, including the majority of those in the New Zealand, Australia and South Africa squads after the WRC had reached out to their respective captains, Sean Fitzpatrick, Phil Kearns and Francois Pienaar.

Ultimately it was the Murdoch-backed unions who would prevail after the Springboks squad’s support for the WRC collapsed under pressure from the controversial president of the South African Rugby Union, Louis Luyt.

While those machinations between players, unions and broadcasters have since been well-documented, what is less well known is just how close the England team at the time came to signing up for the WRC – and turning their backs on the Rugby Football Union.

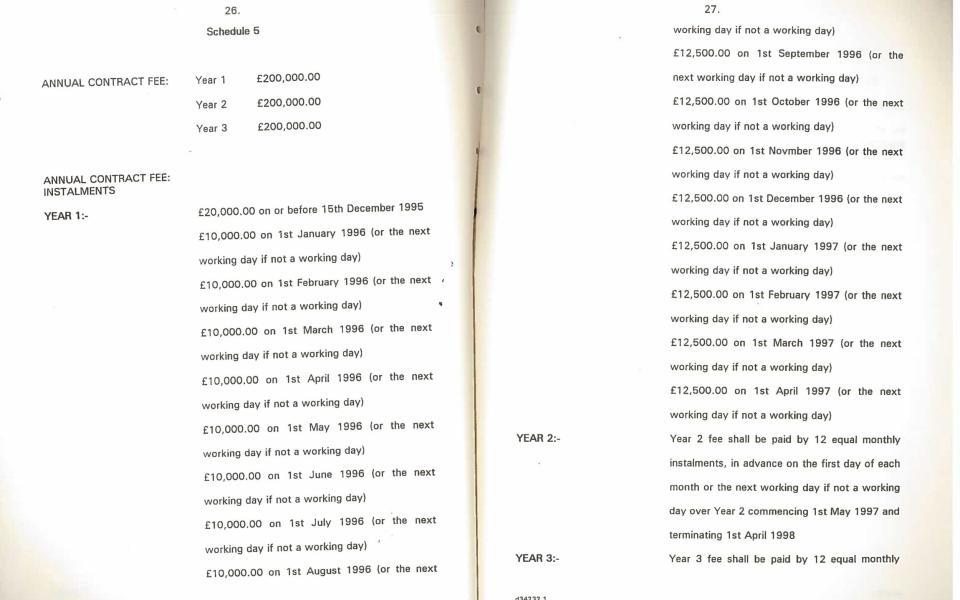

The contract offered to the England players was just as lucrative as it was to their southern hemisphere rivals. The 24-page document, entitled the ‘Deed for the Provision of Services’ included the offer of a salary of £200,000 per season, commencing on Dec 15, 1995, as well as a match fee of £1,350 per game.

The wide-ranging document, which bore the mark of Turnbull Hill Partners, a solicitors firm based in the Charlestown Mall in New South Wales, Australia, covered every aspect of the player’s life in the new global worldwide league that proposed to include 30 franchises across the globe to start in September 1996.

“The Corporation proposes to establish a worldwide organisation for professional Rugby commencing in 1996,” the contract states, even though at the time the game had yet to be declared ‘open’ by the International Rugby Board, the global game’s governing body now known as World Rugby.

“The Corporation wishes to engage the services of the Player to play Rugby for the Corporation on the terms and conditions set out in this Deed.”

The contract was deemed to be confidential, not only including the amount of money being offered but also the very existence of the deed, which was seen at the time to being critical to the success of signing up the best players in the world without the knowledge of their respective unions in the southern hemisphere, who had separately agreed the deal with News Corp.

The players in receipt of the contract offer, however, would have been left in no doubt about the implications of signing it, having effectively to turn their backs on the unions and cede control of future competitions to ‘the Corporation’, including law amendments and discipline.

What is less clear however is where the players would be playing this new professional game. It is only stipulated that they would be allocated a ‘region’ – a territory designated by WRC on or before Dec 31, 1995.

“In the event that the Corporation exercises its rights to relocate the Player, and the Corporation has notified the player two months in advance of its intention to exercise such right, the Player, if he does not wish to play in the team nominated by the Corporation, may have a period of one month in which to negotiate with other teams in an attempt to locate to a preferred team with to accept the Player,” the contract states.

“The player must hold himself available for the selection by the Corporation or any affiliated body and will, if selected, train and play for any representative Team playing the Game and, in any Competition, conducted by the Corporation in any country.”

It was made clear that players would not be able to play for any other team beyond the commencement of the contract, meaning players like Bayfield would have had to turn their back on England.

The level of support promised however is impressive, including all of the player’s “direct costs incurred in performing his duties under this Deed” which included apparel, participation in publicity, strapping and gear, travel to games, accommodation and food, comprehensive health insurance and a disability insurance that would pay 100 per cent of the first year of the contract, and 50 per cent of years two and three if the player were unable to play because of injury.

There was even the foresight to acknowledge the importance of salary caps, signalling that the corporation may bring them in for the benefit of the game and “viability of teams and competitions.”

Given the decades-old battles to align the hemispheres and resolve the conflicts between club and country that were born in those volatile days, what also stands out is the simplicity that the contract attempted to bring to the game that would be known forthwith as ‘rugby or rugby union’.

“Games will, so far as practicable, be organised to take place principally between September and April inclusive each year, HOWEVER, the Corporation reserves the right to introduce a summer competition at any time or from time to time,” it adds.

Whether or not the WRC envisaged recreating a summer tournament to replace the Lions tours is unclear, but significantly Bayfield, a veteran of the 1993 tour to New Zealand, insists that in the turbulent days that followed the 1995 World Cup, the England players were edging towards signing even if it meant they may never have played at Twickenham again.

‘I was earning £28,000 as a constable with Bedford Police’

While the high-brow negotiations involving the southern hemisphere players took place in five-star hotels in Sydney, Johannesburg and Auckland, Bayfield reveals that one of the crunch meetings involving England players took place in the less salubrious location of the Holiday Inn at Crick off the M1.

“When we got back from the World Cup, the East Midlands boys from Northampton and Leicester including Dean Richards and Tim Rodber met up in those delightful surroundings off junction 18 and talked through what the options were,” Bayfield told Telegraph Sport.

“I had doubts about how a game that had been amateur since the day William Webb Ellis was a naughty boy and picked up the ball could go professional overnight and how could the administrators, who were amateur, suddenly become professional administrators.

“But suddenly we had contracts in front of us. They were putting together teams, and you could be placed somewhere a country might need you, such as Australia or America. I am guessing that we were all prepared to sign because the figures and numbers were good,” said Bayfield, who at the time was earning around £28,000 as a constable with Bedford Police.

“It was a fascinating time for the players. We were being asked to make a really big decision. And we were like those vultures in the Jungle Book movie asking each other: “What do you think? I don’t know? What do you think? I have no idea. But we liked the look of the numbers.

“But me being a suspicious police officer, I remember thinking I will only sign this when I know it is going to happen. That’s why I put it in my safe, hence why you have now got it.”

Bayfield says that it was not until the South African players appeared to pull out of the WRC that the concept collapsed, and while the RFU dithered, imposing a moratorium on professionalism for a year, the club owners in England moved to sign up the best players and took control.

“From that moment the seeds which we are now reaping were sown, without a doubt,” Bayfield added, who kept the contract as what he called a “piece of history,” similar to old shirts and match programmes.

“It is a historical document about rugby’s evolution,” Bayfield added. “The RFU are now trying to get these central contracts, but at the time, if they had turned around to the top 100 players in England and said we will pay you £150,000, £100,000 and £75,000 on a sliding scale, we would all have signed and the RFU could then have leased those players back to the clubs and off we go. There would be none of the negotiations between club and country that we are having now.”