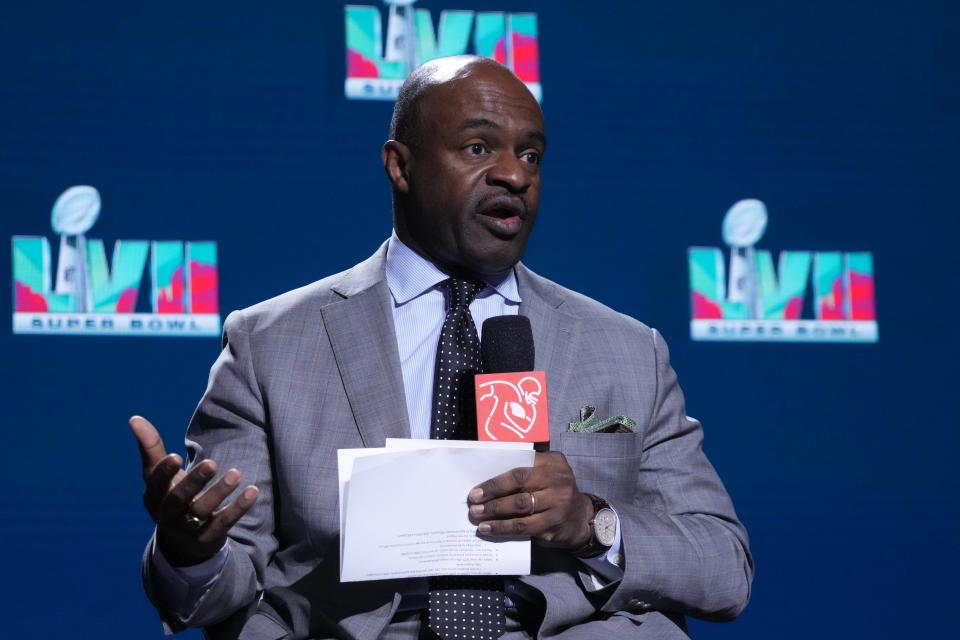

DeMaurice Smith’s legacy: Right man at right time to lead NFL players union

DeMaurice Smith hardly achieved a career goal when he became executive director of the NFL Players Association nearly 15 years ago. No, it wasn’t exactly the “dream job” for Smith, a former federal prosecutor and law firm partner.

But heading the NFL players union turned out to be a fitting destiny.

Smith was precisely the fighter the NFLPA needed in 2009, as the union reeled in controversy following the death of Gene Upshaw as a bitter labor battle against NFL owners loomed.

“It was one of those things where you get thrown in the fire,” Atlanta Falcons defensive lineman Calais Campbell, a member of the NFLPA’s executive committee, told USA TODAY Sports. “But I think he was the right man for the job. Look at the results.

“I’ve had conversations with a lot of guys about a lot of different things. It’s always like, ‘Can you do better?’ We can all do better. I think he did a great job, given the circumstances. He worked hard for us, and I definitely want to respect his efforts.”

As Smith, 59, steps down with the election of Lloyd Howell as his successor, his legacy is enveloped by his reputation as a scrapper – reflected in tone, disposition and with aggressive negotiating tactics – yet is undeniably emboldened by the players’ slice of the NFL’s escalating economic growth. In the current collective bargaining agreement (CBA), struck in 2020, the players are due 48% to 48.5% of the league’s total revenues, the undercurrent to a record salary cap of $224.8 million per team in 2023.

The union’s transition to new leadership is bolstered by the solid pieces in place that Smith secured with the last labor pact.

“As executive director of the union, you are sort of judged by your CBAs, the negotiations,” said Campbell, heading into his 16th NFL season as one of the few players who were in the league during Upshaw’s tenure. “De has had a lot of battles. He’s had to step up and fight for the players in a lot of different ways. It’s not always pretty. When you’ve got 2,000 people, there are always going to be a lot of mixed emotions.

“But one thing you can say is that the salary cap went up a bunch; he’s fought for more opportunities for players to make money, and for health and safety, to be protected on the field.”

The cap ($34.608 million when first instituted in 1994, less than Patrick Mahomes’ current league-high figure of $39.693 million for 2023) has risen over $100 million during Smith’s tenure, which coincides with exploding NFL revenues. Yet Smith, who has preached a foundational theme to players about operating as better businessmen, also joined with other unions to develop a licensing and marketing entity, OneTeam Partners, that has generated more millions.

Then there’s the paradigm shift in NFL workplace rules (for instance, two-a-days were eliminated as a staple of training camps) and the culture surrounding concussions. Smith will go down in history as a key player in these areas. And history will show, too, that Smith helped navigate the COVID-19 pandemic and Deflategate, with the union backing superstar Tom Brady’s lawsuit against the NFL.

Of course, Smith attracted his share of heat. After the 2011 CBA, he was widely criticized for the NFL owners’ ability to win back power and money that had been lost in the 2006 CBA – a monumental win for Upshaw that prompted owners to exercise an opt-out clause which ultimately led to the lockout. The 2011 pact included a rookie wage scale that funneled money from unproven players to veterans. But that turned out as a trigger to nearly wipe out the NFL’s middle class of veterans, with the dried-out opportunities angering many of the player agents. And Smith took it on the chin, too, with NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell retaining his broad power in handing out player discipline.

Still, the pushback wasn’t enough to lead to Smith’s ouster. He survived to be re-elected multiple times, while now positioning himself for another potential career move while serving as a visiting professor at Yale. The 10-year CBA that was questioned in 2011 as being too long? It became a template for the next long-term CBA, which runs through the 2030 season.

The current CBA narrowly passed, with approval from 51.5% of players. It gave NFL owners the long-desired 17-game season, but it also increased the share of revenues for players, up from 47% in the 2011 deal. With increases in minimum salaries, a few more roster spots, tweaks that help players who clearly outplay their rookie contracts, it's a better deal for players this time around.

That it was achieved this time without a lockout or strike reflected a certain type of labor peace that has not been typical with relations between the league and the players union.

That peace is not to be confused with any less willingness for Smith to scrap.

Smith wishes he would have known Upshaw, but he did much to learn the history of previous labor battles that included the Reggie White lawsuit in 1993 that resulted in liberalized free agency, and two strikes during the 1980s (and a failed attempt by the NFL in 1987 to proceed with “replacement players”). He developed a relationship with Upshaw’s predecessor, Ed Garvey, that helped put his challenge into context.

Garvey, who passed in 2017, told Smith, “Don’t doubt your convictions.”

“The best gift that Ed gave me was the comfort and confidence of knowing that we were doing the right thing,” Smith told USA TODAY Sports.

Tom Condon, the powerful agent who represented Upshaw and was a key union leader during his playing days, commended Smith for being the right man at the right time for the NFLPA. When Smith was elected, it was considered an upset in at least one respect: He was the outsider, chosen over three other finalists – Troy Vincent, Trace Armstrong and David Cornwell – who had deep NFL ties.

Yet Smith’s background, and the superb skills as an orator that undoubtedly stood out in a courtroom, provided the union with the presence it needed during a new era.

“It was a fitting tribute to Gene (Upshaw) and his NFLPA achievements that De Smith devoted his legal expertise and esteemed professional reputation to further those achievements and augment them for every player in the league,” Condon wrote to USA TODAY Sports in a text message. “They stand alone in their separate ways in service to NFL players.”

Smith, poised to pursue a bigger footprint as a law professor, will tell you himself that he could have connected better with players in some regards. Others might point to Goodell’s immense power in disciplinary matters as a blemish on Smith’s record. And there are other issues to debate, such as natural grass vs. turf, which the union is seemingly becoming more passionate about.

All told, the NFLPA didn’t go wrong in choosing Smith – even if it wasn’t his dream job.

Follow USA TODAY Sports' Jarrett Bell on Twitter @JarrettBell.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: DeMaurice Smith’s legacy: Right man at right time to lead NFLPA