Community rallies to replace a Jackie Robinson statue after it was stolen from a Kansas little league park

Jaimarius Barnes, an 11-year-old in the Wichita, Kansas-based League 42 baseball organization, planned on suiting up for games this season just feet away from a Jackie Robinson statue.

“He really inspires me because he played baseball and I now play baseball,” Jaimarius said in an interview. “It means a lot. He’s a person you can look up to.”

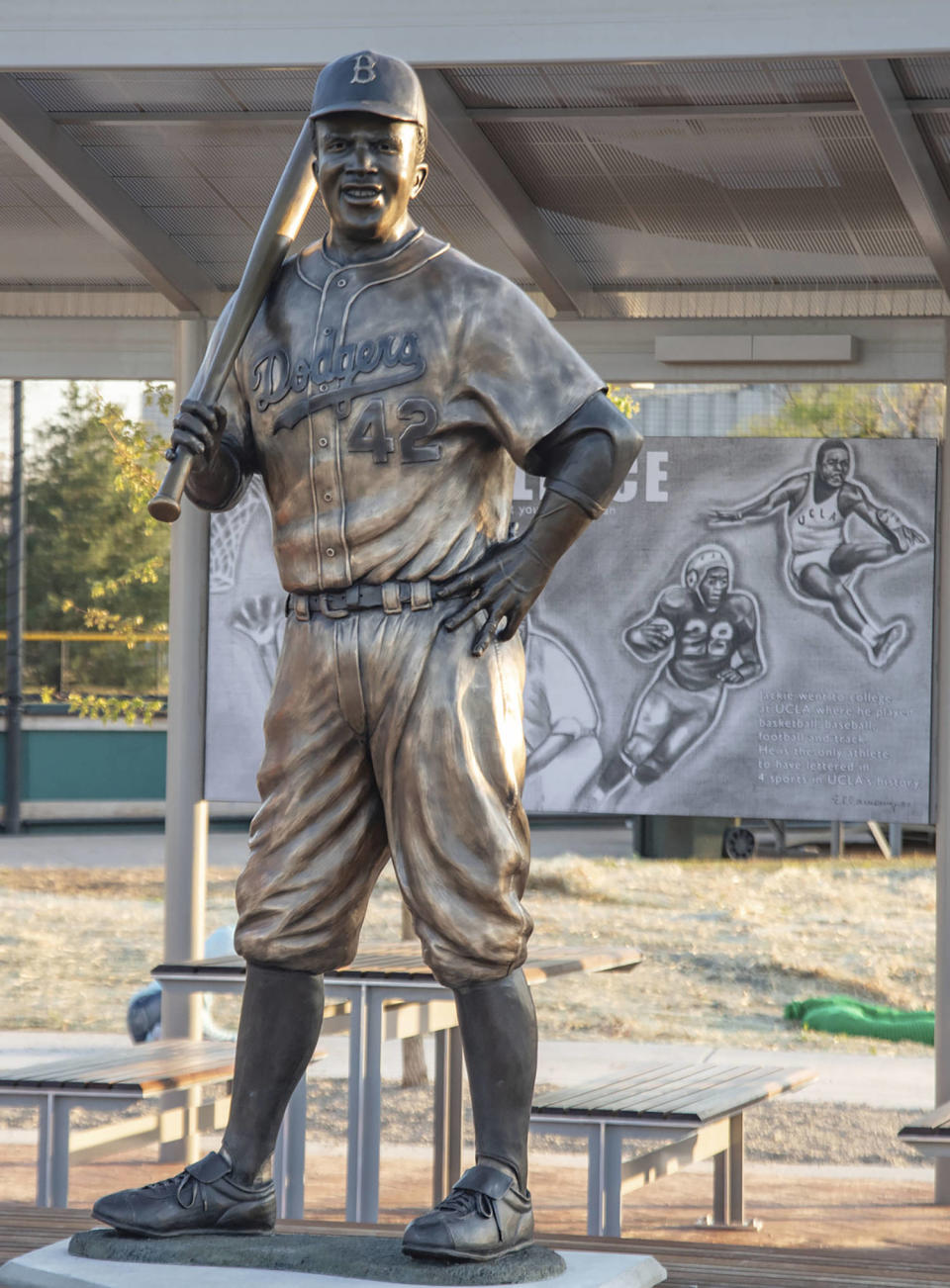

Standing 6 feet tall and weighing 265 pounds, the bronze monument outside the McAdams Park backstop represented hope for Jaimarius and other Black children looking to learn the game.

But back in January, those dreams were dashed. The statue of the legendary Brooklyn Dodgers player and civil rights icon, who broke Major League Baseball's color barrier in 1947, was chopped off at the feet and days later found smoldering in a trash can. Local authorities said there was no evidence of a hate crime and added that the statue appeared to have been stolen to sell off its metal.

News of the incident sparked national outrage.

Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri, said the incident “hits you in your gut.”

Last week, Ricky Alderete, 45, pleaded guilty to helping steal the statue — along with charges of aggravated burglary, aggravated criminal damage to property, interference with law enforcement, criminal damage to property, making a false writing and identity theft. He could face more than 19 years in prison when he’s sentenced July 1, according to ESPN.

But his punishment goes only so far. League 42 needed to replace the monument. And thanks to supporters around the country, that’s exactly what’s happening.

At the time of publication, nearly $200,000 has been donated via a GoFundMe page to raise money for a new statue that is expected to be completed by August. The original sculptor, John Parsons, died in June 2022, but League 42 was able to find the mold he used to build Robinson. “We’re just happy that we can help restore it,” said Shelby Falk, the artists services coordinator for Art Castings of Colorado, “and bring back some history and let John and Jackie’s legacy live on.”

League 42 was created in July 2013 to provide an affordable way for Wichita’s lower-income youths to participate in sports. While many competing organizations cost exorbitant amounts, it’s only $30 for the baseball season, including equipment and uniforms. The league has grown to more than 600 children on 44 teams with improved facilities thanks to contributions from the city.

Bob Lutz, executive director of League 42, said naming the group (and creating a statue) around Robinson was crucial.

“For us here in League 42, it’s a symbol of everything,” he said. “We try to stand for perseverance, overcoming odds, not giving up — everything that Jackie Robinson stood for and was able to accomplish because of those traits.”

Robinson, born in Cairo, Georgia, and raised in Pasadena, California, was a four-sport star at Pasadena Junior College (now Pasadena City College) and UCLA. Racial segregation kept him from playing in MLB, and he instead played for the Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro Leagues.

Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey noticed Robinson’s dominance on the field and signed him to a minor league contract in 1945. Two years later, Robinson became the first Black player in the majors, withstanding constant racial abuse in doing so.

“For Black folks in particular, his breaking of the color barrier carried the same level of euphoria that we saw collectively as a nation when Neil Armstrong walked on the moon,” Kendrick said. “In many ways, Jackie was our Neil Armstrong.”

Robinson’s efforts paved the way for Black players today. According to MLB, entering the 2023 season, 59 players were Black (6.2% of rosters). But a study by the Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport at the University of Central Florida found that figure to be the lowest since it began looking into it in 1991.

“The sport has gotten so expensive that it has eliminated a lot of our kids,” Jerry Manuel, a former manager of the Chicago White Sox and the New York Mets, told The Associated Press this year. “So we’ve got to do everything we can to get them back in the pipeline.”

And that’s why it’s so important for organizations like League 42 to exist. If young players can suit up and aim to one day make it to the professional ranks, those numbers will inevitably increase.

Lorenzo, an 11-year-old player in Wichita, is a prime example. He said that playing baseball is “one of the greatest things that’s happened in my life” and that he plans on taking photos with the new Robinson statue after every game.

Kendrick said the community’s coming together to raise funds for the monument and league is “light coming out of darkness.”

“I want [the players] to embrace the importance of determination,” he said. “I want them to feel empowered to dream. Jackie reminds us that dreams are possible."

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com