'I became a better player': How MLB prospects turned lost 2020 season into a godsend

It was supposed to be the lost season, a year thousands of young ballplayers saw their development stunted, their careers irreparably harmed when the COVID-19 pandemic traced a thick black line through 2020 on every player registry.

And make no mistake: The cancellation of the 2020 minor-league season had a massive impact on countless players. The greatest effect, player-personnel officials say, was likely the premature end to hundreds of careers, what with a new cycle of players churning through and no platform for the old ones to prove themselves. Most would not have made it, anyway, but a few diamonds likely were lost.

Yet now, three years after a global pandemic reduced baseball in the USA to a 60-game Major League Baseball season and a few scattered, rogue circuits, it’s clear a handful of young players benefited greatly from 2020.

With no chance for top prospects to get, in many cases, their first full season under their belt, MLB front offices opted to reserve precious spots for prized prospects in their major league player pool – 60 spots on 30 teams, with more than half of those dedicated to fielding a big league squad.

Other slots were devoted to teenagers and now, those 18- and 19-year-old players have grown up – and in some cases are dominating at the major league level, and guaranteed tens of millions of dollars in salary.

And many believe that would not be possible were it not for the time spent at alternate training sites.

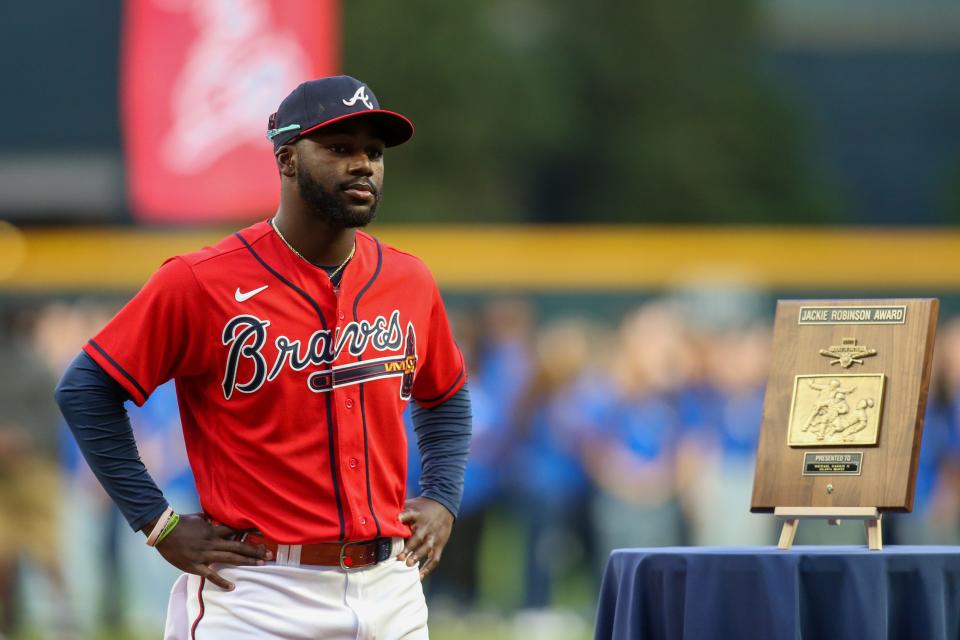

“I felt like it benefited me more than having an actual season,” says Michael Harris II, the reigning National League Rookie of the Year who was just weeks removed from his 19th birthday when he reported to Atlanta’s alternate training site. “Going against those guys every day, with Triple-A and big league talent rather than being in low-A, it felt like an advantage, honestly.

“And I felt like I became a better player in a short amount of time.”

A richer one, too. Harris dominated high A ball in 2021 and needed just 43 games at Class AA – posting an .878 OPS – when the Braves summoned him to Atlanta for his major league debut on May 28, 2022. By mid-August, he had an .870 OPS, 12 homers, 13 steals – and a $72 million contract through at least 2030.

Perhaps it was veteran counsel, more reps against a true major league breaking ball or greater exposure to high-level coaching. Or maybe a late-night meal that bonded future big leaguers. Regardless, the lost year turned fruitful for so many elite young players.

Here are a few tales from the alt sites:

Orioles: Bright future comes into view

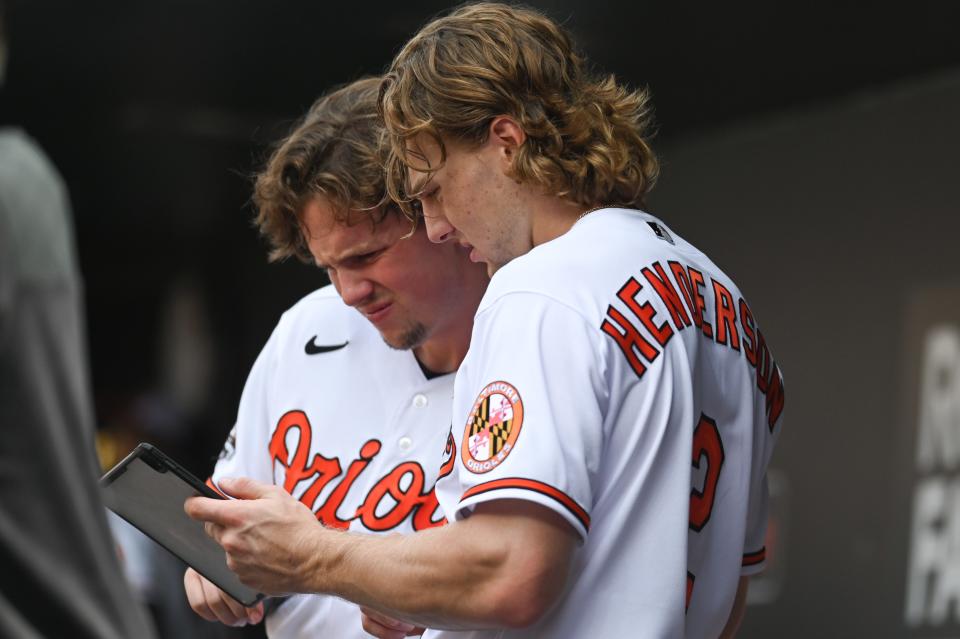

A teenager picked one round after a franchise player is drafted first overall is usually quickly forgotten. Yet Gunnar Henderson took every opportunity to make sure he never left the Orioles’ radar.

Henderson was just 17 when the Orioles drafted him out of John T. Morgan Academy in Selma, Alabama, 41 slots after Oregon State catcher and top overall pick Adley Rutschman became the future cornerstone. Henderson showed well in 29 games at the club’s Sarasota, Florida complex league affiliate, though his tender age meant his first full season would be spent in minor league spring training, with a ticket to a lower-level A ball affiliate in Aberdeen or Delmarva, Maryland.

The pandemic changed that quickly.

With the Orioles coming off 115- and 108-loss seasons, their 60-player pool for the shortened season need not be deep in veterans for competitive purposes. So shortly after his 19th birthday, Henderson reported to the club’s alternate site in Bowie, Md.

He grew up quickly, in all the right ways.

“Getting experience against those caliber pitchers at that age, that was one of the biggest things for my development,” says Henderson, who quickly would follow in Rutschman’s footsteps by inheriting Baseball America’s No. 1 prospect ranking from him. Henderson, at 21, would make his Oriole debut just two months after the 24-year-old Rutschman in 2022.

“Being able to see it at 19 years old, I felt like that was a huge thing for me. I got acclimated to it early and was able to have success on the back end of the alt site.”

It was a process.

Henderson recalls his first we’re-not-in-Alabama-anymore moment came not against a decorated veteran but rather journeyman reliever Eric Hanhold, who has just 13 career major league appearances, in 2018 with the Mets and 2021 with Baltimore.

“I went down 1-2-3, and the last pitch was a 92-mph changeup,” recalls Henderson. “And I was like, well, I guess this is how it’s going to be.”

Not for long. While Henderson said at first it felt like he “got hit in the mouth” by all the advanced pitching at the site, he’d reversed his fortunes by the end. And a year later, climbed Baltimore’s developmental ladder with ease – from low-A to High-A to Class AA, at age 20.

All the while, the alt site provided face time for a core group diverse in age but singular in their goal to reach Baltimore. Prized pitching prospect Grayson Rodriguez, drafted out of high school one year before Rutschman, said it deepened his connection with his future catcher, who’s expected behind the plate for Rodriguez’s Camden Yards debut Tuesday. Rutschman, perhaps the ultimate can't-miss prospect, was hardly slowed in his big league climb - he's posted an .829 OPS in 516 career plate appearances and already has four home runs this season.

The Orioles won 83 games last season, a future coming into focus two summers after incessant DoorDash deliveries and the occasional late-night smoothie run bonded the future stars.

“We got to spend a lot of time together,” says Henderson. “We pretty much spent every night after the alt site together. It enhanced our relationship and pretty much had the idea we’d all be up at the same time.

“It’s been special to have that.”

D-backs: ‘Uncle Trayce’ leaves his mark

Good luck finding official traces of Trayce Thompson’s time with the Arizona Diamondbacks.

He never took an at-bat. Didn’t grace the diamond at Chase Field. And 2020 was just another gulf in what seemed to be a journeyman career, a forgettable gap between major league dalliances in 2018 and 2021.

Oh, Thompson eventually clawed his way back to the majors, and has landed a prominent role on the perennially contending Dodgers. On April 1, he even hit three homers in a single game against the Diamondbacks, further cementing his status in L.A.

Yet a significant part of his legacy was on the other side of the field.

See, in 2020, Thompson was a 29-year-old playing for his fifth franchise in six years, just hoping for a shot with Arizona. Instead, while the varsity played for real at Chase Field, he was confined to Salt River Fields in Scottsdale.

And though he didn’t see a day of big league playing time, he found a mutually beneficial friendship among the dreamers and hangers-on at the alternate site.

“That’s Uncle Trayce! The best,” says Corbin Carroll, just a year removed from a Seattle high school when Arizona tossed him into the player pool as a 19-year-old. “Whenever he’s in town, we’ll go get lunch. He was definitely a mentor to me. He’s just the right voice to learn from and hear from.”

Apparently so. By 2022, Carroll had torn up the minor leagues, arrived in Arizona for a 32-game audition and this spring inspired the D-backs to guarantee him at least $111 million through 2030. It will be an upset if he doesn’t claim 2023 NL Rookie of the Year honors.

For Thompson, playing with – and guiding – literal teenagers such as Carroll and outfielder Alek Thomas was as functional as it was rejuvenating.

“They’re like little brothers to me,” says Thompson, who first met Thomas when Thomas was 10 and the son of White Sox strength coach Allen Thomas. “I’ve known Alek forever. But getting to know Corbin really well is awesome.

“I think I was 28, 29, and that stage of my career was pivotal for me to get those at-bats and kind of improved and worked on my game. Granted, it was instructs, and it felt like it wasn’t real, but it helped me get going in 2021 and getting back to the big leagues.”

It almost didn’t feel real to the kids. Carroll and Thomas were 10 years old the first time Madison Bumgarner pitched in the World Series; suddenly, the three-time champ with the Giants was staring them down from the mound in summer camp.

It was daunting, but probably more instructive than bumping around the Midwest or California Leagues – or not playing at all.

“I just had that gratefulness for being able to play games during a time when a lot of people couldn’t,” says Carroll. “So to be invited to something like that, being around older, better, more experienced competition, at higher levels of minor leagues than I would have been at – that was a very fortunate time for me.

“Bumgarner will probably hate me for saying this, but one of my earliest memories watching baseball was him in the World Series.”

Now, Carroll and Thomas are teammates with MadBum, who yielded Thompson’s grand slam to kick-start his big night. Another fortuitous crossing of paths for a most unlikely trio.

“Trayce is a serious guy,” says Thomas. “I feel like (in) 2020, we brought out a little different side of him, made him smile.”

Rays: A prodigy’s outlet

It’s hard to imagine Wander Franco being anything but self-assured.

Just 22, his four home runs lead the American League, and his hot start to this season – a .351/.400/.757 slash line – show every reason why the Rays guaranteed their shortstop $182 million in a contract extension signed in November 2021.

Yet just days after turning 19 on March 1, 2020, Franco felt something else – scared.

The most vaunted prospect in Rays history – he received a club-record $3.8 million signing bonus – had just one full season of minor league ball under his belt. And now, season No. 2 had been taken away.

“It was really tough knowing there was no season,” Franco said through interpreter Manny Navarro, “because that’s what we live for. We live for the season, it’s what we play for.

“It was very tough that year.”

But the Rays were wise to protect their investment. Even with little chance Franco would help a club that would go on to win the AL in the shortened season, they added Franco to their alternate site roster in Port Charlotte.

By the time Tampa Bay advanced to the World Series, Franco was able to shake the baseball world up with a simple Instagram story depicting his Rays jersey with a World Series patch on it.

Oh, he was just on the taxi squad. But he also was just eight months away from his major league debut, and far more seasoned thanks to a number of veteran Rays who took him under their wing in Florida.

“I thank God those (veteran) guys crossed paths with me,” he says, “because we needed that help in that time.”

Braves: Get ‘em in, send ‘em up

On March 8, 2020, Spencer Strider gave up four runs and struck out five Boston College batters as a Clemson Tiger. The next time he picked up a baseball in an organized setting, he was one step from the big leagues.

Such is life as an Atlanta Brave, an organization where future All-Stars Freddie Freeman, Jason Heyward and Ronald Acuna Jr. all debuted at 20. That aggressive push has not changed over the years – and the Braves are reaping the benefits.

Strider could barely unpack his bags after COVID-19 canceled his season at Clemson before the Braves drafted him, signed him and soon shipped him to their suburban Atlanta alternate site. It was there that he and Harris’ climbs toward big league greatness began.

They’d finish 1-2 in 2022 NL Rookie of the Year voting and sign contract extensions worth a combined $147 million. But first came a summer in Gwinnett County, a haven in an industry otherwise shut down.

“It was nice to get to go play, to have a locker, to have practice,” says Strider, who was chosen in the fourth round by Atlanta. “Most people weren’t getting that opportunity. For me, it was just nice to have a schedule and have something to do outside of what I was doing on my own.”

Strider downplays the role the alternate site played in his development but consider this: Just 10 players chosen in the 125 picks before the Braves chose Strider have reached the majors. And none have approached Strider’s impact – he reached Atlanta by late 2021 and last year struck out a stunning 202 batters in 131 2/3 innings.

Essentially, he was the pitching version of Harris, who made his own noise at the alternate site.

In his first live batting practice session, he faced none other than Ian Anderson, who would make his major league debut a month later and shortly thereafter post 17 ⅔ scoreless innings to start his postseason career, including a Game 7 NLCS start.

Harris took him deep, a fact he almost sheepishly admits.

“Yeah. That happened,” he said, as if he’s still the unheralded 19-year-old and not a budding All-Star.

The challenges continued, against hard-throwing Touki Toussaint, future big league starter Kyle Muller, eventual World Series starter Tucker Davidson. Veteran utilityman Charlie Culberson was in his ear as needed, urging him to be himself, to not try to impress everybody, that he was good enough.

It wasn’t lost on Harris that this was a luxury the vast majority of his 2019 draft mates did not enjoy.

“For them, it had to be a bad feeling,” he says. “Especially coming off being drafted and not having a season. You had a month and a half of baseball and now you’re off for a whole year. It hurt some people and helped a lot of others.”

Strider’s experience was more controlled, confined to another side of the complex with fellow inexperienced pitching prospects. Now, after experiencing three spring trainings, he knows that typical camps involve a handful of instructors with 60 or 70 pitchers to monitor. At the alternate site, his learning curve greatly accelerated with a system’s worth of instructors and just a couple dozen arms.

“They were able to give more one-on-one help,” he says, “and that was invaluable at the time.”

With benefits that are still paying off.

Contributing: Bob Nightengale

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: MLB prospects turned lost 2020 minor league season into a godsend