Back in 1984, Olympia saw the ‘biggest bidding upset in the history of the Olympic Games’

Two-time world marathon record holder Jacqueline Hansen had two questions when she woke up in a hospital bed on April 16, 1984, the day of the Boston Marathon.

“I wake up on a hospital cot with dog tags around my neck and the doctor is saying my body temperature’s below 93. And I just looked at him – my teeth are chattering and I can’t stop shaking – and I just looked at him and said, ‘Did I finish? What was my time?,’” Hansen told The Olympian in a phone interview.

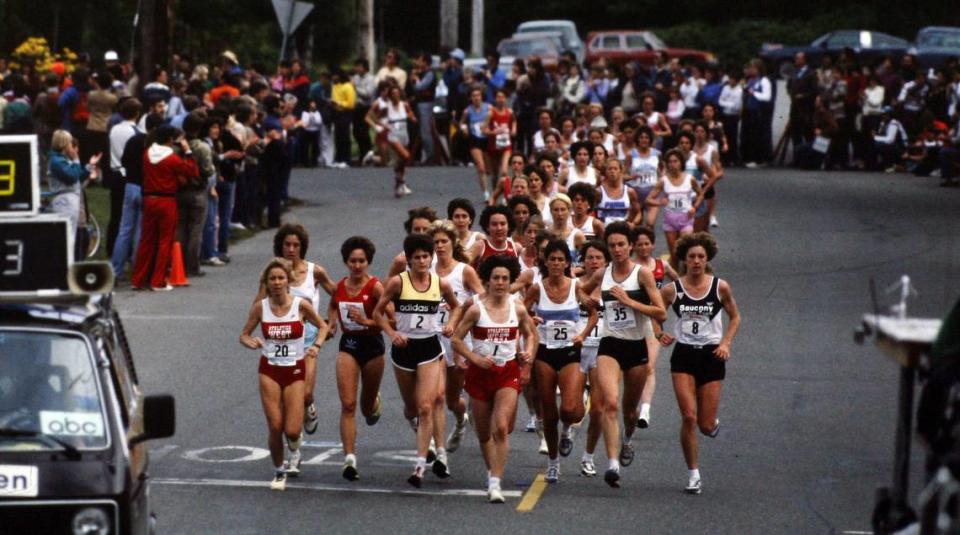

Hansen, who helped lead a lawsuit against the International Olympic Committee to get the women’s 5,000 and 10,000 meters included in the games, had been at the forefront of the push to get the women’s marathon in the Olympics. She was the most accomplished female marathoner in the world at the time, but the longest distance event at the games for women was the 1,500 meter.

“So here I was, 1974 to ‘77, holding the world record twice and not having an Olympics to go to, because the longest event was only the mile, only the 1,500 meter. So it began as a personal crusade,” Hansen said.

When, in 1981, the International Olympic Committee finally announced that the women’s marathon would be included in the ‘84 games, the prime of Hansen’s running career was over. She was 35 years old and nine years removed from her second world record, a 2:38 marathon in Oregon that made her the first woman to run the race in less than 2:40. But the Olympic trials were still in reach.

“Once we got that marathon in there, by golly, I was going to be on that starting line no matter what,” Hansen said.

Taking place just four weeks before the trials were set to be held in Olympia, Boston was Hansen’s last chance to qualify. She started the race well ahead of the qualifying mark of 2:51, but by the 25th mile, she had started to lose her vision and didn’t remember finishing the race when she woke up in the hospital.

“She comes back and tells me I ran a high 2:47 – so if you round up, like 2:48 – and I was in 14th place. So I know that I lost four places and four minutes in that final mile,” Hansen said. “But I still qualified. I made it.”

40th anniversary of the trials

Hansen is one of 60 alumni of the 1984 trials who will be returning to Olympia this weekend for the 40th anniversary of the race.

“We’ve had four events,” Denise Keegan, chair of the Olympia Trials Legacy Committee, said in a phone interview. “This will be our largest event that we’ve put on.”

The Legacy Committee is hosting an entire weekend of events, scheduled around the Capital City Marathon on May 19, to mark the 40th anniversary. First, a private reception for the athletes will be held on Friday, May 17 at the governor’s mansion. Keegan said she wanted the event, which has been in the works for a year, to be a chance for the runners to reconnect.

“Although they may have maintained contact, some of them haven’t seen each other in 40 years,” Keegan said. “So this is going to be a special occasion for them.”

Later that night, the athletes will be at a banquet at the Indian Summer Golf and Country Club. The banquet is open to the public but only with the purchase of a ticket. Admission is $75 and tickets can be found on the event’s website.

Among those in attendance will be Joan Benoit Samuelson, who won the trials in ‘84 before going on to win gold at the games in Los Angeles three months later.

“It’s hard to believe it’s been 40 years, but I guess according to the calendar it has been. And I’m certainly feeling 40 years older,” Benoit Samuelson said in a phone interview with the Olympian.

Benoit Samuelson’s win was even more remarkable considering she ran at the trials just 17 days after a surgery to repair an injury in her knee.

“I literally ran that race on a wing and a prayer,” Benoit Samuelson said. “And fortunately, my wings were working and my prayers were answered.”

Saturday’s panelists

Saturday, May 18 will have plenty going on too. Local running group Club Oly Road Running will host three panels between 11:30 a.m. and 3:00 p.m., in addition to a run earlier that morning. Both are free and attendees can register on the event’s website.

On a phone call with the Olympian, Jennifer Vazquez-Bryan, Club Oly’s vice president and event planner, said that she wanted to find a way to get the community involved in the anniversary festivities.

“I’m a physician, and one of my patients gave me a poster from the 1984 trials. And when I was looking at it, I was like, wow, that’s 40 years ago, is there an event happening? Because I haven’t heard anything,” Vazquez-Bryan said. “I found out that they were kind of organizing something, but that it was really mostly a reunion for the women. And I was like, ‘Oh, we really need to include the running community.’”

Benoit Samuelson and Hansen are both scheduled to speak on the panels along with Peggy Kokernot Kaplan, a fellow ‘84 trials alum, and Laurel James, who came up with the idea to host the trials in Olympia.

“I wanted to come back because I want to really see these people. I want to meet these other women that I competed with,” Kokernot Kaplan said in a phone interview. “I want to hear their stories.”

There’s one competitor in particular that Kokernot Kaplan wants to see.

“The only memorable moment was when this Sister Marion (Irvine) from California, age 54 I believe, passed me. I’m like, ‘Oh my gosh, this nun has just passed me by.’ My understanding is she is going to be there,” Kokernot Kaplan said. “I hope she comes, because I want to go up and ask her for a rematch.”

Like Hansen, Kokernot Kaplan was instrumental in bringing the women’s marathon to the Olympics. In 1977, Kokernot Kaplan was one of several runners asked to carry the National Women’s Conference torch from Seneca Falls, New York and Houston, Texas, where the convention was held.

Outside of the conference, she was approached by Hansen, who introduced herself and gave her one request.

“She said, ‘If you have any chance to mention that we would like to have a marathon in the Olympics, if you get interviewed, we’d really appreciate it.’ And I said sure, not expecting to be interviewed by anyone. But sure enough, I was interviewed by Time Magazine and appeared on the cover of it.”

Competing events

At the same time as the panels, the Legacy Committee will host a meet-and-greet during the Capital City Marathon Expo at Sylvester Park.

Vazquez-Bryan said she was hoping to not have the events conflict.

“There felt like there was just kind of some politics. So we’re like, ‘Okay, we’ll do anything and we’ll do the best that we can,’” Vazquez-Bryan said.

Keegan said she isn’t worried about the time conflict, though.

“There are a lot of events going on on Saturday,” Keegan said. “That is one of many.”

What the trials mean 40 years later

After four decades, it’s still as remarkable as ever that a city of Olympia’s size got to host an event so important to the national sports landscape, according to Keegan.

“There was a woman named Laurel James out of Seattle who had come up with the idea. She thought tying the Olympia name in with the Olympics would be a fun thing to do,” Keegan said.

After she and her son presented their idea to the Capital City Marathon, a delegation led by former Washington Supreme Court Justice Gerry Alexander and then-Senator Slade Gorton flew to Philadelphia to deliver Olympia’s pitch.

Their pitch worked, and Olympia beat out Los Angeles, New York City and Kansas City.

“There is a sports writer in Seattle that shared with me that when Olympia got the bid, it was arguably the biggest bidding upset in the history of the Olympic Games,” Keegan said.

While Keegan said Olympia’s win brought accusations that the small city over-promised, the participants remember feeling more welcomed than they would have in a bigger city.

“Olympia and the race organizing committee certainly rolled out the red carpet for all of us,” Benoit Samuelson said.

Hansen agrees.

“I think Olympic trials should always be awarded to smaller towns than big cities,” Hansen said. “You get a lot more attention. You get a lot more appreciation.”

The trials also marked a key moment in the history women’s participation at the Olympics.

“When I talk to people, every time, I’m like, can you imagine, women were only allowed to run in the marathon in the Olympics 40 years ago? Like, that’s not that long ago,” Vazquez-Bryan said.

For Hansen, how far the women’s marathon has come in the past 40 years is even more clear. The same day she qualified for Olympia, she found out that she had lost the initial hearing in the lawsuit to get the women’s 5,000 and 10,000 meters on the agenda.

“The L.A. Times reporter called me back and said, ‘You lost in court today,’” Hansen said. “That was like the highest, high and the lowest low of my entire running career all in one day”

That year, 23% of the participants at the Olympics were women. But shortly after the Olympia trials, both the 5,000 and 10,000 were named as future Olympic events. This summer, the Olympics will feature as many women as men for the first time in its history.

“Even though we lost in court, you can lose a battle and win the war, right?” Hansen said.