NLCS Game 2: Justin Turner, Kirk Gibson will forever be linked to Oct. 15

LOS ANGELES – Sometimes Leonys Martin can hear the crowd, sometimes he can’t. It’s weird that way, out in center field, so far away from the ball and the bat, where the sound of the contact almost comes after the contact itself, like it’s chasing his eyes, and then the cacophony of shrieks and cries and shouts and woos falls into itself, somewhere outside his head, and he’s just running. He’s just chasing. And hoping.

On Sunday night, he could not hear the crowd. He did not know why. In a moment, he saw that the swing was good, that the finish was high, that the ball was coming toward him, and then almost before the thought registered he heard how well that ball was struck, and then it was just him and the grass and the dirt and the wall. He did not see the ball go over the wall, because the wall is so big, and what he knew was he’d reached the wall and, well, there was nothing left to do.

“I thought for one second,” he said, “that the ball wasn’t going to go out. That’s why I ran, just put my head down and ran. I thought for a little bit. Just for a little bit.”

It was warm at Dodger Stadium on Sunday night. Even so, even without the marine layer that typically comes with October, all the stuff that causes so many disgusted U-turns between first and second base, a home run at night to center field at Dodger Stadium is a grown-up’s home run.

So, when Justin Turner had hit the ball that would become the most celebrated home run in this town in exactly 29 years, that being the ball that left his bat with two out and two on in the bottom of the ninth inning Sunday night, in Game 2 of the National League Championship Series, he too was curious. He too knew better than to assume the best, that the pitch was perfect, the swing was perfect, and the conditions wouldn’t ruin it all. Hadn’t he just three hours before hit a ball to almost the same place, to the wall, and been robbed of a hit? He’d need 400 feet on that ball, maybe more if Martin was feeling springy, and so he watched and he could hear the people shrieking and crying and shouting and wooing, and it worked up inside him too, until finally he let go of his bat and put his arms in the air.

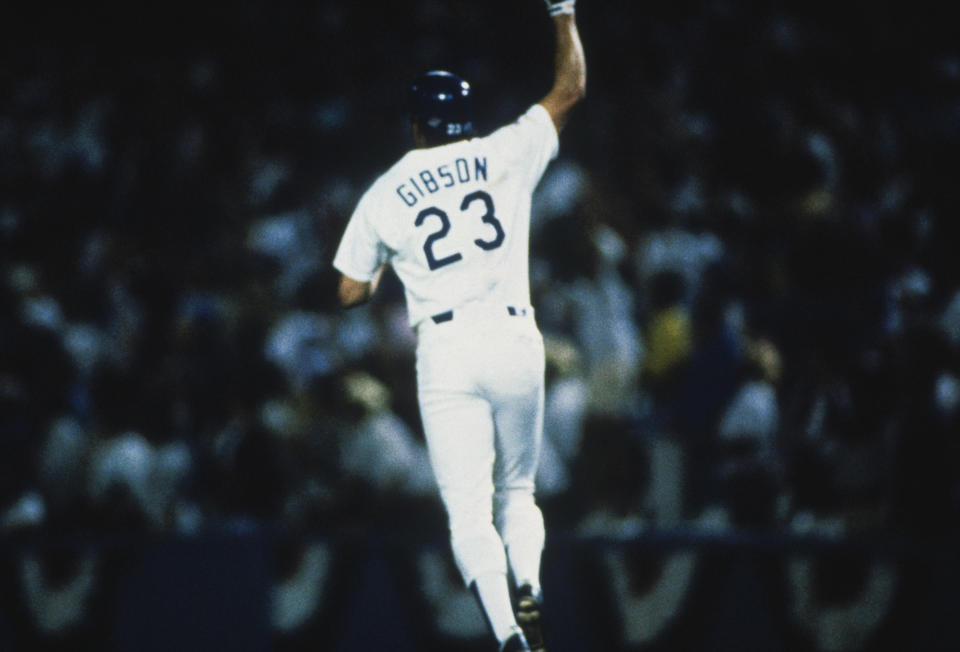

He’d gotten 416 feet. That would be plenty. He’d gotten three runs, also plenty, for a 4-1 final score. Twenty-nine years to the night since he’d watched from his grandmother’s living room as Kirk Gibson flicked a baseball into the right-field bleachers, leaving him breathless then, Justin Turner had delivered the second postseason walk-off home run for the very same franchise.

“Yeah,” he said, “I can’t even put into words right now. It’s incredible. The most important thing was, obviously, helping us get another win. But that’s something down the road, hopefully, many, many years from now I’ll get to tell stories about.”

John Lackey is 38 years old and if the only time you ever saw him was when an umpire’s call went against him or a reporter asked a question he found beneath him, which sometimes seems like most questions, you’d think he was about fed up with all this crap. Course, that’s been going on for almost 20 years. Within 15 minutes of the pitch that ran this series to two-games-to-none, Dodgers, Lackey was ready to go, his hair wet from the shower, him wearing a crisp dress shirt, a conservative sport coat and a sneer.

He’d of course thrown the pitch Turner hit and Martin chased and the rest of the Cubs trudged away from, and you could reasonably argue he probably shouldn’t have been the man throwing the pitch, but it happened anyway. It was a fastball, the second pitch of the at-bat after he’d bounced a slider with the first, and Lackey’s body of work would show two batters faced, one walk to Chris Taylor and one extremely hittable fastball to the Dodgers’ best hitter. Lackey wasn’t much in the mood for particulars, but that pitch started on the outside part of the strike zone and then veered into the middle of the strike zone, where Turner’s bat barrel was waiting. Asked if that baseball was supposed to stay away from Turner or continue on toward Turner, Lackey’s eyes narrowed and he summoned a smirk and said, “Uh, yeah, I’ll talk to my pitching coach about that.”

Ultimately it didn’t matter, really, what it was supposed to do, only what it did, and then what Turner did to it, chasing Martin to the base of that wall and turning Dodger Stadium into a place that believed again. Again. They do make a run at this October thing fairly often, and last year it was the Cubs who finished them, and it still could be the Cubs who finish them this year. But, in the meantime, Turner, who’d had all of two postseason at-bats by the time he was 30, has, at 32, snuck up on something special. He was a .370 playoff hitter in 22 career games as of Sunday afternoon, and then he walked again, and singled home a run, and homered in three more by the end of Sunday. His orange hair flopped around, and his orange beard ruffled, and he arrived at home plate with a smile and his arms wide. He fell into the arms of his manager, Dave Roberts, and they hugged for a long time.

“It’s unbelievable,” Roberts said. “It’s – what did you say? Twenty-nine years to the day? It was special. Our guys feel it. We feel it.”