Long before Tepper and Jordan, a forgotten man pioneered pro sports in Charlotte

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Before David Tepper, Michael Jordan, George Shinn and Jerry Richardson, before the big money came in and the local football stadium looked like a modern Roman Colosseum, there was a pro sports owner in Charlotte whose name you’ve most likely never heard.

Let’s change that today, because Bob Benson was a Charlotte sports pioneer who shouldn’t be forgotten. Benson died Jan. 20 in Charlotte following health complications brought on by a fall, at age 83.

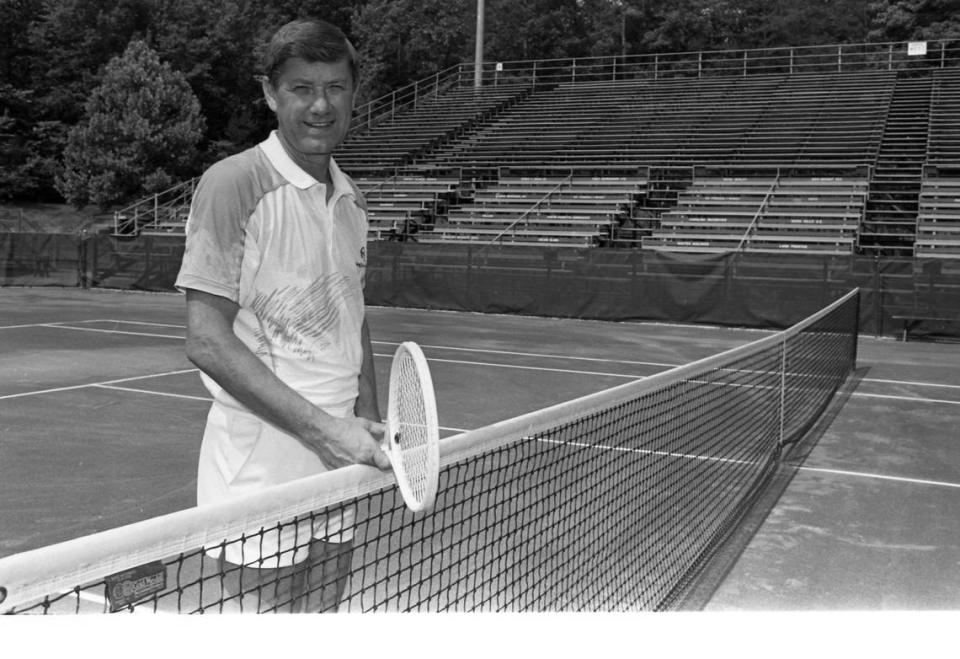

Back in the early and mid-1980s, where the Charlotte pro sports scene mostly meant NASCAR, minor-league baseball and what most people referred to as “rasslin’,” Benson was the innovative owner of the Carolina Lightnin’ pro soccer team and then the Charlotte Heat, a pro tennis team that competed in World TeamTennis.

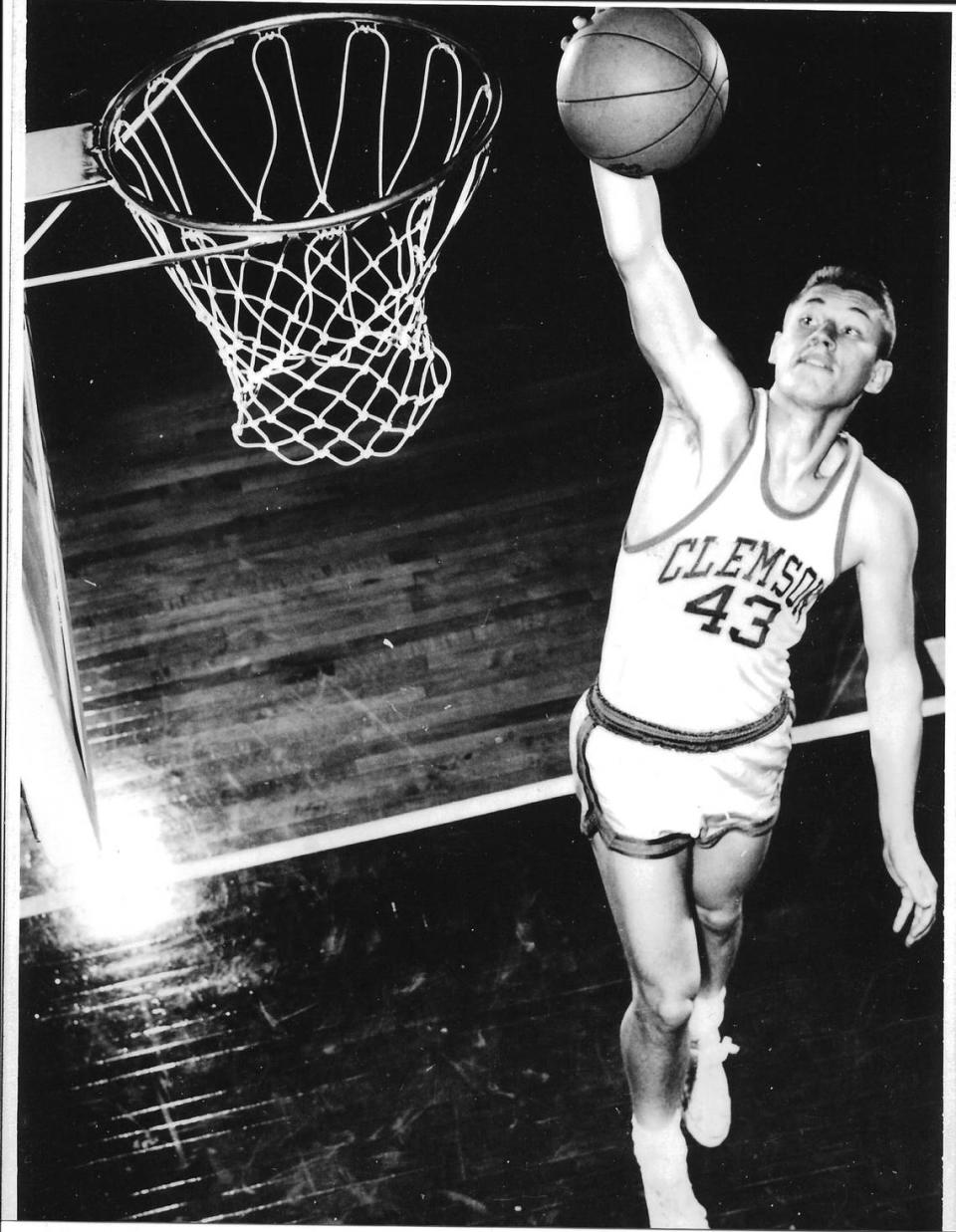

His teams won championships in both sports and sometimes played to sellout crowds. Benson brought the same competitive spirit to promotion (a Beach Boys concert! An airplane giveaway!) that he honed at Clemson as a scholarship basketball player and co-captain in the early 1960s.

Billie Jean King, the tennis legend and longtime driving force behind the WTT, still remembers Benson. Although it’s been 30 years since he fielded a team in her tennis league, she responded within minutes when I contacted her about his death.

“Bob was a world-class tennis promoter and I have fond memories of packed crowds at the Olde Providence Racquet Club gathering to support the Charlotte Heat,” King said. “His team won the WTT championship twice in the first two years of the franchise and Bob always had two goals when it came to the team — put on the best show possible and win the championship. It was our honor to have him in the WTT family.”

For Shinn, who founded the Charlotte Hornets in the late 1980s, Benson’s soccer success earlier in that same decade was an inspiration.

“Bob Benson got 20,000 people to a soccer match in Memorial Stadium in 1981 — 20,000 people! For soccer!’ Shinn said in a telephone interview. “You better believe that had an influence on me. I saw that and I thought, ‘Wow, what a market Charlotte is. If we can actually get an NBA team in here, we’re going to blow the doors off.’ ”

Benson was the sort of entrepreneur every city covets, a member of the “creative class” before the term came into existence. Originally from Pennsylvania, he went to Clemson to take a basketball scholarship (he played under Press Maravich, Pete’s father) and then moved to Charlotte in 1963 to take a job. He never left and, before long, had started his own company.

Although Benson owned and ran his own business for 39 years — an industrial sales engineering firm called PNUCOR that specialized in pumps and filters — he liked to have 2-3 big things going on at one time. That, and his belief that Charlotte was underdeveloped in terms of pro sports, led to his team ownership.

Owning the Carolina Lightnin’ and Charlotte Heat was never lucrative. The soccer team, at the least, lost a lot of money. But the teams brought Benson joy while simultaneously filling a hole in Charlotte’s sports community and proving the market was ready for more.

Benson and his wife of 61 years, Marjory, had one child, a son. Said Mike Benson of his father: “At heart, Dad was a salesman. And that’s really where his strength was. He had a way of getting people to do what he wanted them to do. He never was threatening or intimidating. He just convinced them that what he wanted to do was what they wanted to do, too, and that it would be great.”

A soccer novice — and pioneer

Benson knew hardly anything about soccer when he decided to pursue owning a team in the American Soccer League, which at the time would have been the equivalent to the Triple-A baseball version of the sport. He mainly knew basketball and baseball; besides playing hoops at Clemson, he had briefly pitched until Press Maravich told him he had to pick one sport.

But his son was an avid youth soccer player in Charlotte and Benson was intrigued by the sport’s potential. And he truly was frustrated that Charlotte didn’t have more pro sports. In the 1970s, he had been part of unsuccessful lobbying groups that tried to keep the ABA’s Carolina Cougars playing games in Charlotte (they moved to St. Louis in 1974) and golf’s Kemper Open from leaving the city (it did, in 1980).

In some ways, Benson was 40 years ahead of his time in his pursuit of high-level soccer for Charlotte. In 2019, Tepper paid an expansion fee of close to $325 million for the rights to get Charlotte a Major League Soccer team, with the idea it would share a stadium with his Carolina Panthers. Charlotte FC is scheduled to debut in MLS in 2022.

In 1981, soccer wasn’t nearly as mainstream in America, and the average Charlotte sports fan often needed a reason to be persuaded to drive uptown to Memorial Stadium.

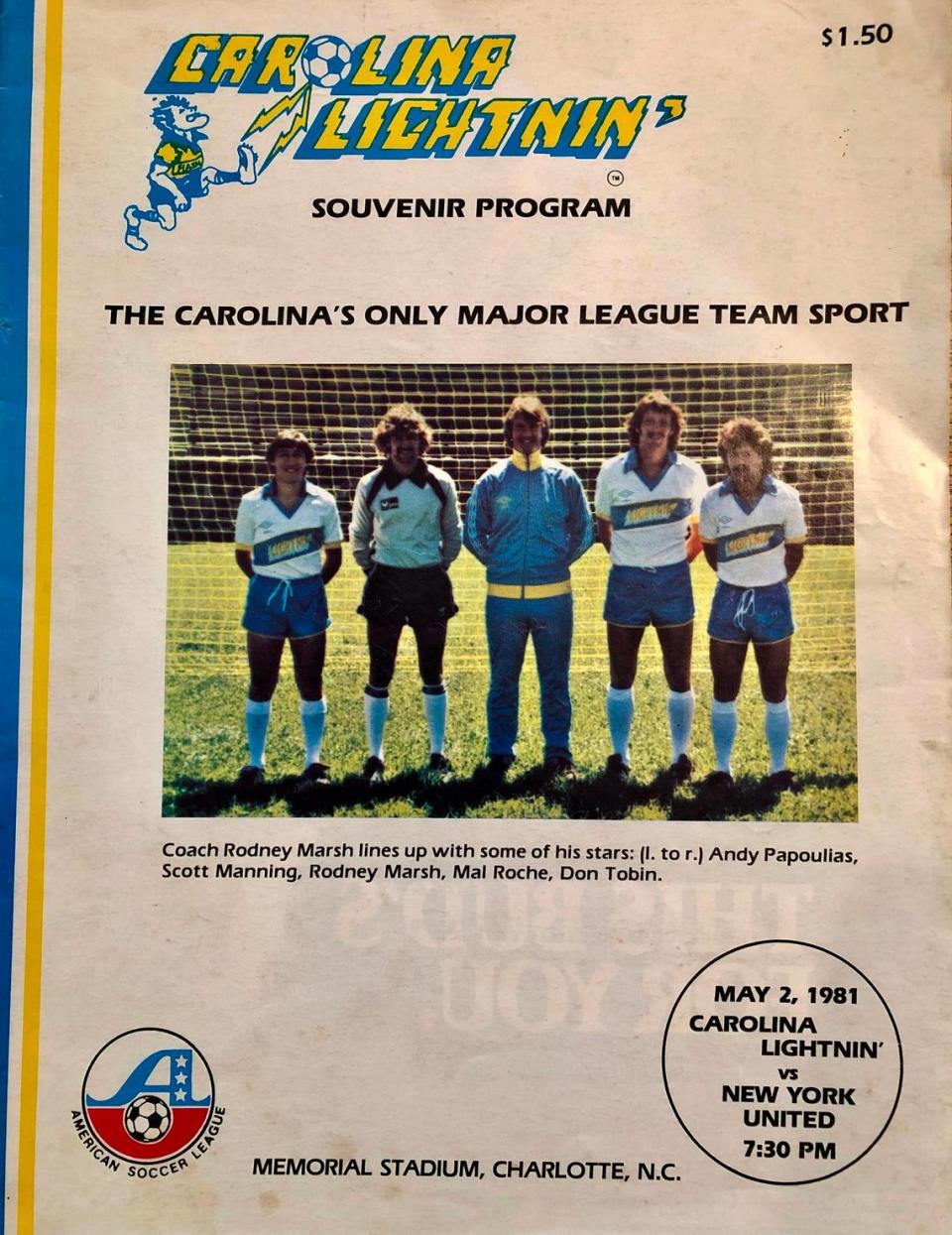

Benson tried to give them one, first by hiring Rodney Marsh as coach and general manager. Marsh was an English soccer star and, fortunately for the Lightnin’, had just filmed a national Miller Lite commercial that was getting major airplay in the U.S.

“Hiring Rodney Marsh had to be one of the top three moves Bob Benson ever made for that soccer team,” said Ed Young, who was the director of operations for the Lightnin’. “Here we had this famous soccer player, and a charismatic guy, and he was doing the same sorts of Miller Lite commercials as (NFL stars) Dick Butkus or John Madden. That really helped provide some identity for us.”

Benson quickly dispatched Marsh to every speaking engagement in and around Charlotte he could book, drumming up support for the new team. Marsh, for his part, quickly found out how competitive Benson was.

“We would play tennis sometimes,” Marsh said. “It would start getting dark, and it might be tied at two sets all, and I’d say, ‘That’s enough for today, Bob.’ But he’d say it wasn’t. We were going to be staying out there long enough for him to get the win. But let me tell you — our players loved him. Absolutely loved him. He treated them like family. And that’s partly why, 40 years later, that soccer team is still so close.”

Giving away an airplane

The Lightnin’ famously drew an ASL-record 20,163 fans to Memorial Stadium in uptown Charlotte to see its championship game in 1981, which Carolina won, 2-1, to take the league title in its rookie year. But other nights weren’t nearly as lucrative. Young said the team averaged about 6,500 fans per game over its three-year run, and Marsh said it was more like 4,000 on many nights to play teams like the Pennsylvania Stoners and the Jacksonville Tea Men.

To make ends meet, sponsors had to be found and promotions had to be planned. Young recalled a time when two competing car dealers in Charlotte were accidentally both sold the idea of becoming the “Official Car of the Charlotte Lightnin’” and the mistake wasn’t noticed until both dealerships saw the painted infield signs at Memorial Stadium — one proclaiming Chevrolet as the official car and one proclaiming Volvo.

A loud argument ensued, Young said, and Benson was brought in to try and control the situation.

“Mr. Benson said, ‘Let’s work this out, guys,’ ” Young recalled. “How about this? I’m going to give you a good deal on the sponsorship, and I’m going to make Chevrolet the official American car of the Lightnin’ and Volvo the official foreign car of the Lightnin’. And both of them actually agreed. So I told our painter, ‘Hey, go get your paintbrush,’ and we fixed the signs that night.”

The Beach Boys concert was another coup, as the team drew about 14,000, Young said, for a postgame show. The Beach Boys requested and received a large playpen to be placed on the soccer field to help corral their young children during the show, Young said.

Then there was the plane giveaway, undoubtedly the Lightnin’s most famous promotion.

Benson, Marsh and Young decided giving away cars was too common and decided to make a splash by giving away a new four-seat airplane, made by Piper and retailing for about $35,000 at the time. A sheet of durable paper that was thicker than newsprint was inserted inside editions of The Charlotte Observer, Young said. Fans had to bring that sheet to the game, write their name and phone number on it and fold it into a paper airplane.

After the game, the plane was rolled out to midfield. Fans lined up anywhere in the stands — but not on the field — and threw their airplanes, knowing that the person who got a paper airplane closest to the bottom tip of the real airplane’s propeller would win. There was no limit on the number of airplanes you threw, so The Charlotte Observer sold a lot of newspapers that day.

“I think we had about 12,000 people there for the game,” Young said, “which was a huge crowd for us. At the end, they were standing around the side, jockeying for space. Some went up high into the stands, trying to get more air under their planes. And then we blew a whistle and there literally must have been 50,000 airplanes thrown onto the field.”

Benson held a tape measure to the bottom edge of the propeller and the men measured the nearest paper airplanes and determined a winner.

What would most people do with an airplane, you ask? In this case, there was a contingency plan.

“The guy who won could sell it back to the dealership for something like $25,000 and take the cash,” Young said. “Which he did.”

From soccer to tennis

Despite the splashy promotions, the ASL was faltering as a league. Charlotte was one of the league’s stronger markets, but everyone was losing money.

It was hard to sell soccer then. It went almost unnoticed that the Lightnin’ actually used Marsh’s assistant coach Bobby Moore as a player for a few games. Moore had captained England’s team that had won the World Cup in 1966 and was a soccer legend overseas, but he was in his early 40s by the time he coached and played for Carolina. It was as if Willie Mays had finished his career playing for an obscure English minor league team, but in Charlotte, it didn’t move the needle much.

After the 1983 season, the ASL folded. Benson kept running his “real” business, but he got out of the soccer business for good. The Observer reported in 1987 in a story about Benson that the Lightnin’ lost about $400,000 altogether in its three years of existence.

At that point, though, Benson was onto his next sports venture. “Charlotte does not have a pro sports reputation,” he said at the time. “We’re hoping this will be a positive kick in the right direction.”

This was World TeamTennis, a franchise that began a year before the Charlotte Hornets. Billie Jean King appeared at a 1986 Charlotte press conference with Benson, saying she had approved a Charlotte team primarily because she believed in Benson.

“You have to have the right person,” King said of Benson. “He definitely made it (soccer) happen here.”

Benson was already looking for another championship by then, telling The Observer in 1987: “In 20 years with my business, I’ve never had a bad year. I want to diversify. I want to win. I want to beat that other owner. It’s the hunt thing. You want to go after something. I’d like to win the championship in the first year like I did in soccer.”

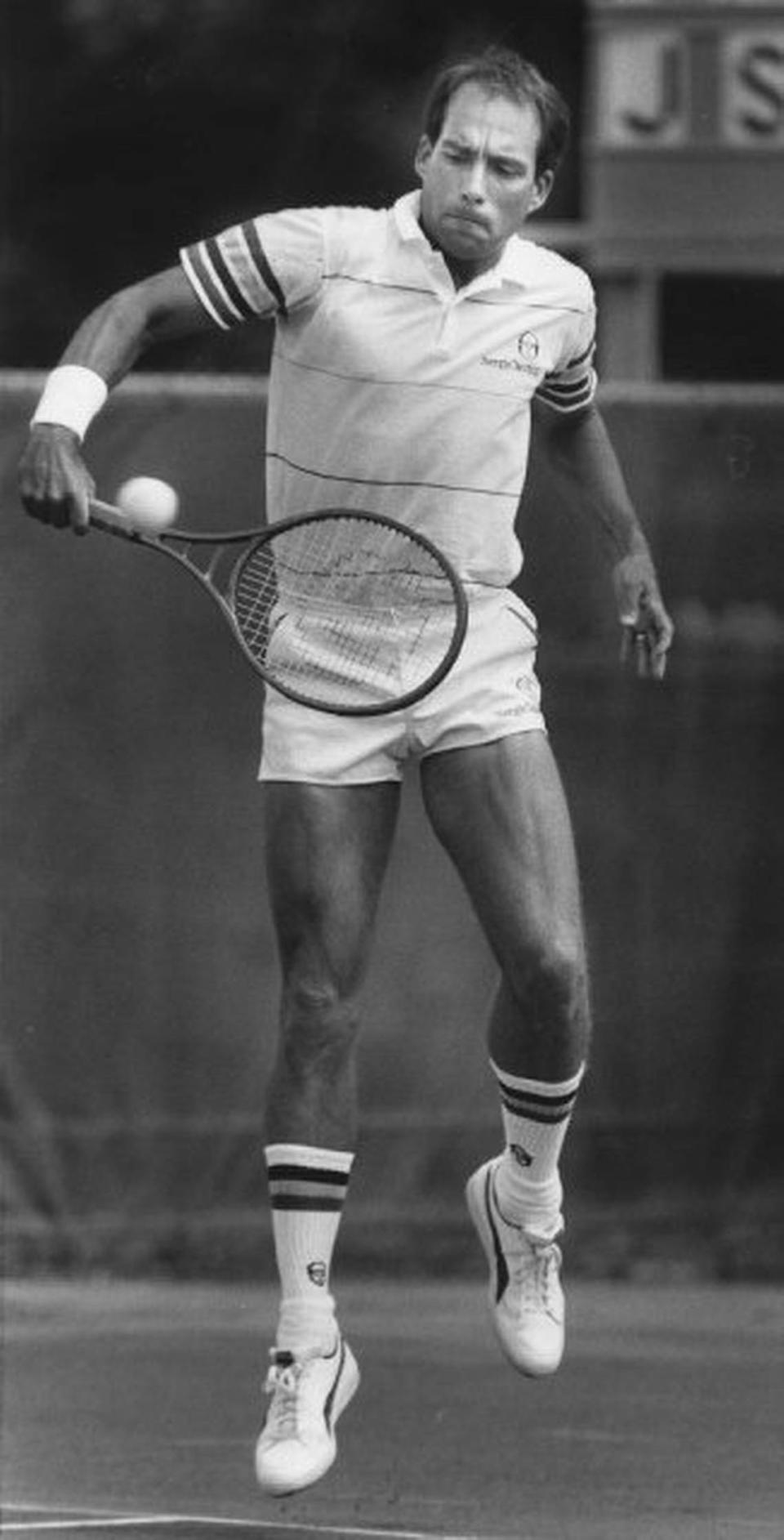

That’s exactly what the Charlotte Heat did, sometimes drawing as many as 5,100 fans to Olde Providence. Homegrown players like Tim “Dr. Dirt” Wilkison and John Sadri helped the Heat to two straight championships in 1987 and ‘88. The Charlotte fans were raucous enough that they once caused a league controversy by being called for a point penalty in a critical match (Benson protested, unsuccessfully). Shinn was a minor sponsor for the yet-to-debut Hornets and again would marvel at the passionate crowds Benson’s teams could draw.

“We had a Hornets banner there once, and sometime after the first match it got stolen,” Shinn said. “I thought that wasn’t bad actually — it meant that people were interested in us, too.”

Benson had become a good age-group player in tennis, even though he didn’t take the game up until adulthood. “He was passionate about bringing sports to Charlotte,” Sadri said. “Really, he was passionate about everything. One time we were joking and he said: ‘I don’t think your serve is that great. I bet I could return it.’ ”

Sadri was known for having one of the top serves in pro tennis. The two lined up across from each other, and Sadri declared he could ace Benson four times in a row. Benson promised him a trip to the U.S. Open golf tournament — Sadri was also a devoted golfer — if he could do it.

“I aced him three times straight,” Sadri said, laughing. “He didn’t come close to any of those. But Bob was smart, and the fourth time he moved back almost to the fence. I went down the middle and this time he just barely nicked it. So, officially, no ace. He decided my serve was pretty good after all, but I didn’t get that golf trip.”

Excited until the end

In his late 40s, Benson began to suffer from chronic fatigue syndrome, according to his son Mike. The disease would plague him for nearly half his life. Still, he was able to run his business.

But Benson gradually had to slow down on his other sports pursuits. By the early 1990s, the Hornets were an NBA revelation, Richardson was close to winning an NFL team for Charlotte and Benson no longer owned the Charlotte Heat. He rapidly faded into the background as the city’s new teams dominated the headlines. It wasn’t an unfulfilled life, but it was a quieter one.

Benson satisfied his sports itch mostly by holding season tickets for Clemson football games, playing tennis and shooting baskets with his three grandchildren in the backyard. He was still doing that until a few months before he died, even when one grandson had to steady him between shots.

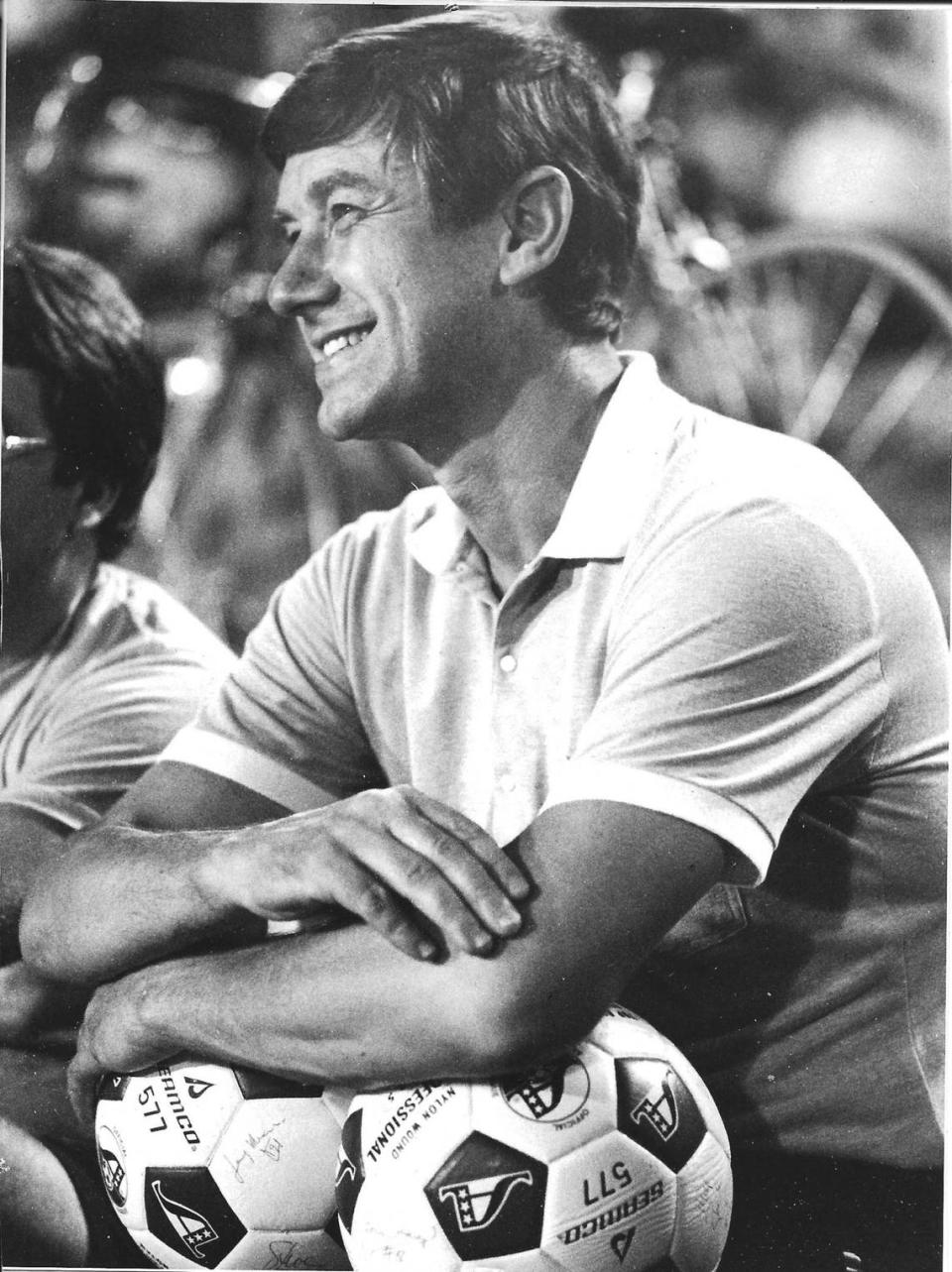

“We have this picture of Dad in the 1980s with some soccer balls, and you can just tell from the look on his face he is so excited,” Mike Benson said. “And that’s how he was. High energy. Up early. Always had an angle on what he wanted to do next. Wheels turning. And he really didn’t let anybody tell him ‘No’ — that was just something he never accepted. He went through life excited, always looking for the next thing. And that’s not a bad way to go through life.”