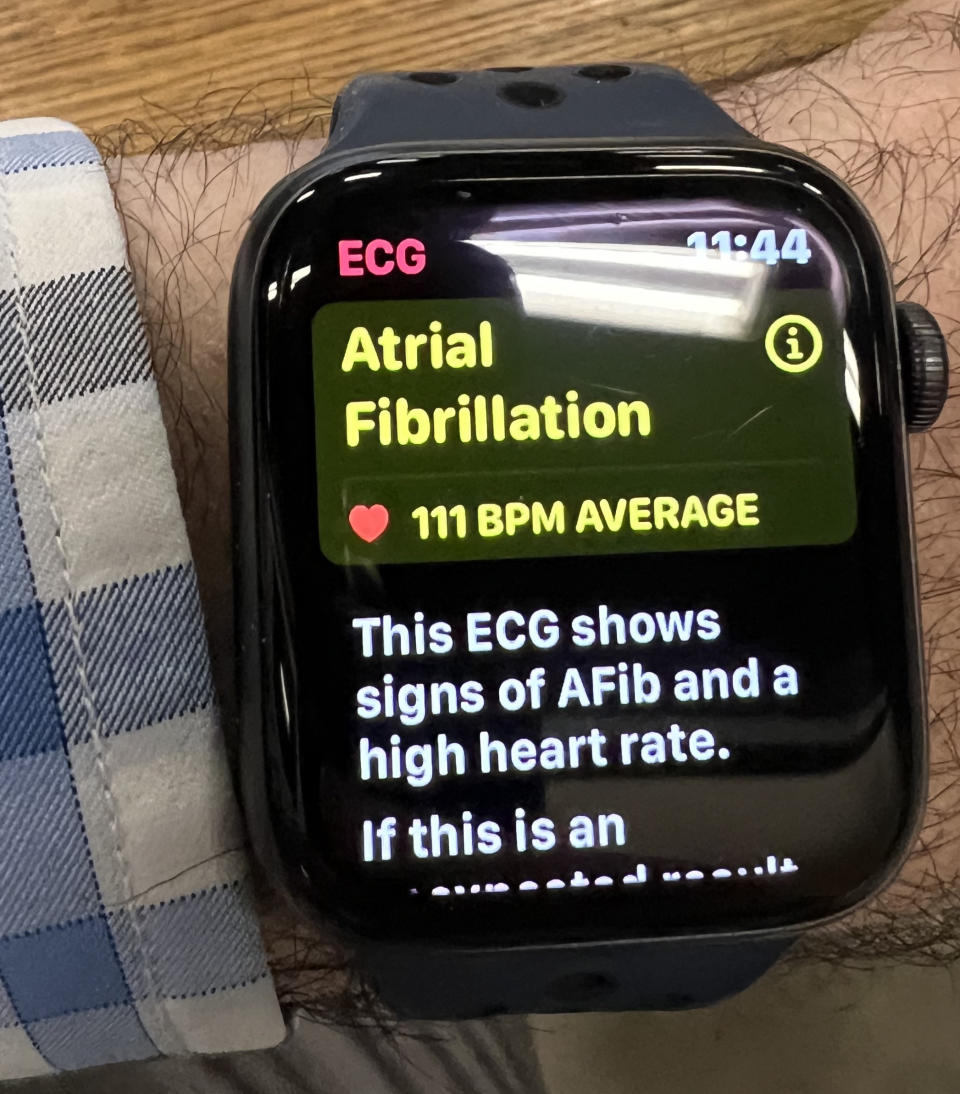

I got diagnosed with Atrial Fibrillation — how I'm learning to be a cyclist with a wonky heart

It started with a thump.

Wait, let’s go back a bit.

I’m a 53-year-old man, and I’ve been a cyclist in earnest since the days of blue Gitanes, toe clips with Binda straps, and when Davis Phinney reigned as the king of criteriums.

I’m sure many of you can agree that once an activity is done enough, it pretty much becomes a part of the way a person is defined. For example, if someone were to approach and say “so, tell me about yourself”, one would assume, as you are reading this, that “I’m a cyclist” would eventually make its way into the conversation.

I’m a cyclist. Perhaps to a fault.

About eight weeks ago, I woke up with a funny feeling like some kind of Keebler Elf was playing bongos on my sternum. And not very well. His timing was horrible. If he were in the Beatles, Paul would re-record his tracks. My heart rate, sitting at my desk, was just over 130. It is normally just under 60. This was not normal.

I've had this feeling in the past, normally after I treated my body like an alcohol-soaked Disneyland. You know, the weekends where long rides are followed by beer, wine and some form of low-budget, screw-cap bottle hard stuff. Yeah…weekends when my body got so dehydrated, my heart would decide to shift into self-sustain mode and focus strictly on keeping me alive.

But this was different.

Atrial Fibrillation is defined as an irregular and, at times, rapid heart rate that sets the top chambers of the heart (atria) and the bottom (ventricles) into a tempo that basically resembles the sound and feel of those moments when two cars blasting their stereos come to the same stoplight. The atria are cranking the syncopated jazz while the ventricles are sticking to mellow soft rock.

In case you didn’t know, the heart is kinda important to, well, existence. So when the chambers of the heart get so out of sync, one can deduce that multiple issues can arise, such as dizziness, fatigue and even a stroke. Blood pools in the heart, which can greatly increase the chance of those dreaded clots being released into the bloodstream.

Cycling is a healthy activity. Cyclists aren’t supposed to have these issues. The common thought is that the more time spent on the bike, (barring distracted drivers, road ragers and random incidents of gunfire) the longer and better the quality of life. Right?

Lennard Zinn is also a lifelong cyclist. If you’ve worked on your own bike, chances are you have learned from one of the “Zinn and the Art of” books, read one of his articlesor, in my case, spent time with his book “The Haywire Heart.” At age 55, still competing at a high level, Zinn developed heart issues that would result in heart rates over 200 BPM on a consistent basis, along with occasional issues of his heart stopping for 3-5 second intervals while sleeping.

What he discovered is that the research for endurance athletes and cardiac issues has been under-researched. At the time of his issues, the majority of information regarding cardiomyopathy was done on what Zinn describes as the typical “cardiac patients: the overweight, smokers, non athletes, etc.”

However, there has been an increase in reported cases, especially since the rise in endurance related sports’ popularity. For those of you old enough to remember the running boom of the 1970s, it was around then that the popularity of endurance sports came about in the United States. Athletes who took to the streets in those days are now of the demographic potentially showing signs of cardiac issues.

But what causes it? According to Zinn, “Genetics can likely play a role. What also can lead to issues is scarring of the heart. Scarring happens because your heart tissue no longer has the flexibility it had when you were in your 20s. Hard training and racing would deliver large amounts of blood volume to the body to keep up with the demands.” Often referred to as Athlete's Heart—a physiologic response where the heart becomes larger and more efficient than average as a natural response to intensive exercise.

“Then, if you de-train, your heart would return to its original shape.”

This is what is supposed to happen. Kind of like the Grinch, but instead of doing good deeds, the cyclist is doing interval training.

Think about it this way, Zinn described it using the skin on the back of the hand. As one ages, the skin on the back of the hand becomes thinner and less flexible. Over 40? Try it right now. Notice that the skin is not as pliable as it was in your 20s. That process is happening all over your body. Continuing to ask for that same kind of blood volume in your 50s, asking the heart to enlarge as it would in your 20s, when it is no longer as flexible as it was leads to what Zinn refers to as “micro tears in the myocardium.”

When those micro tears heal, they cause scar tissue, which then can cause disruptions in the electrical signals in the heart. Mixed up electrical signals means you’re back at that stop light with Miles Davis and Roxette.

Now, try going for that Strava KOM with a heart producing about 20-50% of it’s effective capacity. Not going to happen.

Personally, I’ve been off the bike for several weeks, introducing myself to a daily dose of beta blockers (to keep the heart rate lower), blood thinners or anti coagulants (to reduce clots that can lead to stroke), and have already gone through a cardioversion procedure of shocking the heart back into proper rhythm. For a cyclist, these three items mean a lower heart rate which makes strenuous efforts more strenuous, thin blood that won’t clot should a cut or crash happen on a ride, and a procedure that worked really well, for about two weeks. I’m back in Atrial Fibrillation after a short ride ended abruptly.

In other words, this is a cycling-killing condition.

What are the options, you may ask?

The next step is ablation. According to The Mayo Clinic, Cardiac ablation uses heat or cold energy to create tiny scars in the heart to block irregular electrical signals and restore a typical heartbeat.

But wait, isn’t scar tissue the bad guy in this story? Zinn brought it home…“Given that we know that the substrate for arrhythmia is the scarring of the heart, and then going in with ablation and creating more scarring of the heart, it seems inevitable to me that a lot of these (patients) are going to come back.”

Great. Guess I’ll just hang up the wheels now.

Or maybe not.

In my situation, ablation is actually great option. It can potentially remedy the AFib for an extended period. Each situation is different for each patient, so as my fibrillation can be helped by this procedure, we can call this “good scarring”.

Zinn gave me some good advice from this dark situation. “Be patient with yourself” was the first thing. Second was to find a proper doctor that understands the passions and lifestyle of the endurance athlete, especially a proper Electrophysiologist.

So I have. Rides still happen. I’ll even throw in some efforts. But I’m also a constant user of the ECG function offered by my Apple Watch, my diet is monitored and the post ride beer happens a bit less often.

Cyclists are a stubborn and passionate group. Pain is a part of the fun. However, keeping an eye and ear open to issues is something all followers of the two wheeled lifestyle should always maintain.

To quote the aforementioned Roxette,

“Listen to your heart when he's calling for you

Listen to your heart, there's nothing else you can do

I don't know where you're going and I don't know why

But listen to your heart before you tell him goodbye”

She’s right. Should you be experiencing heart issues outside of the norm, check your watch, visit a proper doctor, and “be patient with yourself”.