As Auschwitz exhibit opens in Kansas City, memories haunt this Holocaust survivor

She is one of the last survivors of Auschwitz in the Kansas City area.

On Sunday, Elizabeth Nussbaum, soon to turn 94, was set to enter Union Station for a special viewing of some 700 artifacts from the Nazi concentration camp that in May 1944 killed her mother, her father and her six brothers and sisters only moments after they were disgorged from a suffocating railroad box car from Hungary.

Awaiting her and visitors to the exhibit: a red, high-heeled shoe displayed in a clear case, set against a photograph of a mound of shoes from some of the 1.1 million Jews and others murdered there in its notorious gas chambers and by other means.

A striped uniform like the one she wore as a prisoner and slave laborer, her head shaved to bristle, at age 16.

The desk of Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Höss, one of the most nefarious mass murderers in history.

But no matter how powerful or informative “Auschwitz. Not Long Ago. Not Far Away.” may be (the exhibit opens Monday and runs through January), Nussbaum said she is already certain it could never impart the day-to-day horror of a Nazi concentration camp. Or the lifelong toll.

“They cannot bring in what was,” Nussbaum, of Overland Park, said recently, seated next to a walker in her living room, her soft Hungarian accent still prominent. A thick book about the exhibit showing its displays and 400 photographs sat at her side. “They cannot show the real thing.

“Can you show that a soldier took a child and threw it against a wall?… We saw the chimneys burning. I’ve seen people being hanged because they tore a piece of their blanket, to show, ‘You do something wrong, that is what is going to happen.’”

An exhibit cannot recreate the terror and inhumanity she felt standing outside naked, her body checked for bruises and health, to determine, on a whim, if she would be selected to live as slave labor or die.

“Anytime I think about something, not only do I feel it, I see it,” she said. Even in recent years, her caretaker said, memories of the Holocaust have disturbed her in her sleep. “It’s there in front of me. It’s in your system. It’s built in and will never leave.”

Born Elizabeth Weiss in August 1927, she was raised in the Hungarian town of Szerencz, about 130 miles from Budapest. Her mother, “a hausfrau,” she said, raised the children and kept the home. Her father worked as a Jewish official checking dairy to make sure it was kosher.

Nussbaum said that to this day, the rumble of trains reminds her of how how she, her family and all the Jews of her town were rounded up, expelled from Szernecz and forced for six weeks into the Jewish ghetto of Sátoraljaújhely, which she called Ujhely. They were then pressed into a railroad boxcar and shipped as human cargo to Auschwitz-Birkenau in German-occupied Poland.

More people would be murdered at Auschwitz than at any other of the camps designed to carry out Adolf Hitler’s “Final Solution,” the extermination of the Jews.

The train traveled for three days.

“Children were crying, especially babies, because they had no milk,” Nussbaum said. “There was no toilets. There was nothing. … Even today, it hurts to see a baby crying.”

People died as the train rolled on, the living pressed against the dead. The train crawled to a stop inside Auschwitz. The Nazis separated the men from women, the young from old.

Nussbaum was sent one way; her family another.

“They told us that we were going to see the parents and the siblings on Tuesday,” Nussbaum said. “We arrived, I think, on a Sunday. But Tuesday never came, because a half an hour later, they weren’t alive.”

The Auschwitz exhibit

The exhibit’s opening on June 14 coincides with the day in 1940 that the first Polish prisoners entered Auschwitz, considered the camp’s inception. It’s scheduled to close shortly after Jan. 27, International Holocaust Remembrance Day, the anniversary of the day the camp was liberated.

Luis Ferreiro, the CEO of Musealia, the Spanish company that conceived of the exhibit in collaboration with Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum in Poland, acknowledged that the point of the exhibition, although it often evokes strong emotions, is not to play on those emotions.

“I always feel very stupid, because what can I explain to somebody who has been in Auschwitz?” he said last week, as workers from the Auschwitz museum and elsewhere placed their final touches on assembling the exhibit. “This is only shadows of Auschwitz. Nothing in this exhibition is meant to replicate or try to make people feel what those people felt, because that is impossible and, intellectually, it would be dishonest to do it.”

Nussbuam was to be among a select group of local Holocaust survivors being given a private preview tour of the exhibition through a collaboration with the Midwest Center for Holocaust Education in Overland Park.

“When I work with survivors,” Ferriero said, “most of them are satisfied that we are trying to spread the word of what happened and explain what happened in a way that is respectful to the memory of the victims, and it’s also focused very much in understanding the underlying principles of the story.

“It’s not just about coming to see artifacts. It’s about how a place like Auschwitz could come to exist in the first place, how it was possible, and what does it mean to us today.”

Nussbuam survived three months in Auschwitz. She labored daily under the threat of death, working where she was commanded, in the kitchen, for an officer, carrying railroad ties to support the train that transported Jews and others to their death. Nussbaum was then shipped some 500 miles away to Dachau, the Nazis’ original concentration and slave labor camp in southern Germany.

The exhibit at Union Station shows The New York Times from the January day the Soviet army liberated Auschwitz-Birkenau and notes how, although the name Auschwitz (German for the Polish city of Oswiecim) would soon become infamous worldwide, news of its liberation did not make the front page. Instead, it was initially noted in a single paragraph on an inside page:

“Fifteen miles southeast of Katowice in industrial Silesia, Marshal Koneff’s troops captured Oswiecim, site of the most notorious German death camp in all Europe. An estimated 1,500,000 persons are said to have been murdered in the torture chambers of Oswiecim.”

Dachau was liberated by U.S. troops on April 29, 1945, only a little more than one week before May 8, when victory in Europe, V-E Day, was declared.

Nussbaum recalled seeing U.S. planes overhead. Nazi guards, she said, had begun fleeing the camp. Days before U.S. soldiers arrived, 25,000 prisoners were forced to march south away from Dachau or to waiting freight cars.

“During these so-called death marches,” the United States Holocaust Museum notes, “the Germans shot anyone who could no longer continue; many also died of starvation, hypothermia, or exhaustion.”

As U.S. forces neared, “they found more than 30 railroad cars filled with bodies brought to Dachau, all in an advanced state of decomposition.”

Elizabeth Nussbaum was 18 years old.

Eyewitness to a monster

Her daughter, Bonnie Mannis, an attorney now living outside of New York City, still chokes with emotion to talk about what her parents endured. Her father, too, Polish and Jewish, was also a Holocaust survivor and the only one of his immediate family to live.

“Everyone perished. Everyone was murdered,” Mannis said.

Sam Nussbaum, seven years older than Elizabeth, was born March 23, 1920. The two met after the war in Italy in a displaced persons camp. They would stay there three years, marry, have their first child, Larry Nussbaum, who became a Kansas City area physician.

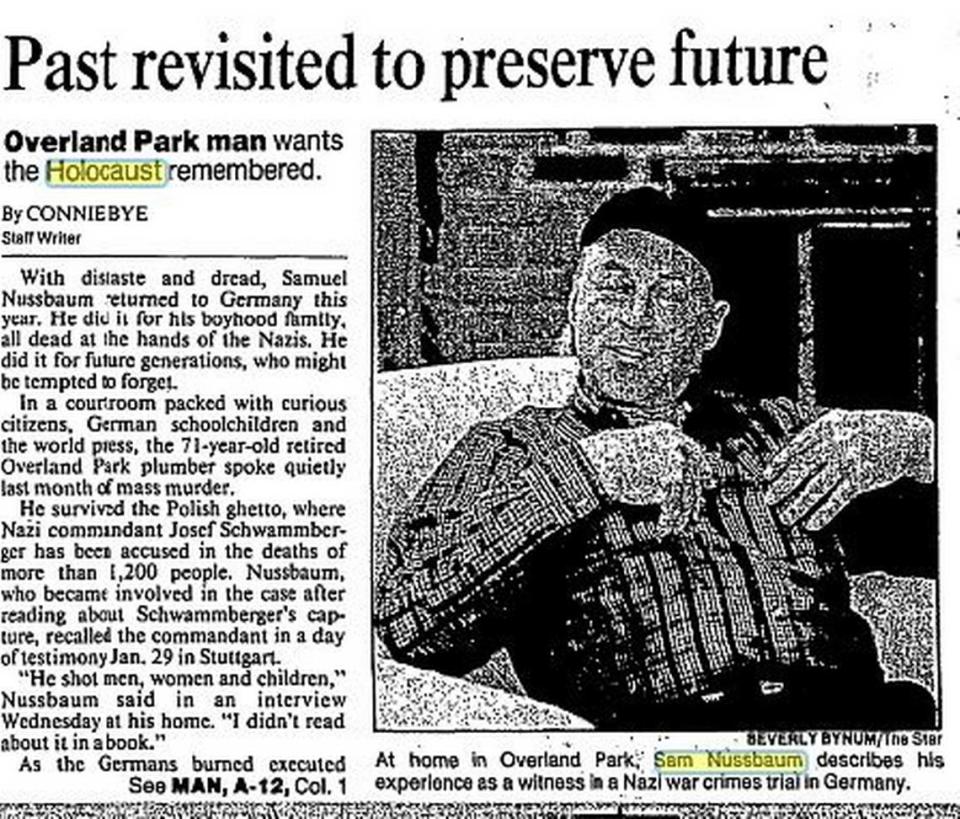

In January 1992, The Washington Post profiled Sam Nussbaum, then 72 years old and a retired Kansas City plumber , when he traveled to Stuttgart, Germany, as an eyewitness in the trial against Nazi war criminal Josef Schwammberger. Mannis keeps a copy of the newspaper story.

The Midwest Center also maintains an archive containing the audio and video testimonials of dozens of Kansas City area Holocaust survivors, many of whom have died since the recordings were made. Among them are testimonials by Sam Nussbaum, who died in 2002 at age 82.

He talks of Schwammberger, who had been the commandant of Ghetto A of the Polish city of Przemysl. When Schwammberger arrived in 1943, the ghetto housed 28,000 Jews. No more than 100 remained by war’s end.

“He was a murderer, was killing. I seen him shooting about 30 people,” he recounts in the recording. “Just told ’em to get undressed, he shot every one of them. I looked on it. “

In 1945, French soldiers arrested Schwammberger after they found him carrying eight sacks stuffed with diamonds and gold tooth filling. But he soon escaped a military transport taking him to trial in Austria. He found a safe haven living in Argentina under his own name and protected by Argentinian authorities.

Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal and the West German government won his extradition in 1990.

In his 20s when he was in the ghetto, Sam Nussbaum was always mechanically inclined. He said that Schwammberger allowed him to live because he was useful. The SS officer used him as as a kind of personal engineer, doing odd jobs, such as building a fence, a laundry, a distillery to make vodka for Nazi officers.

At trial, Sam Nussbaum was one of more 100 witnesses, some of whom traveled from as far off as the U.S., Israel, Canada and Australia, to testify that Schwammberger was directly involved in more than 1,200 murders.

“It’s very painful to go back 45 years and wake up all your wounds,” Elizabeth Nussbuam told The Star in its own 1992 profile upon their return. Nussbaum said that when she saw Schwammberger, then 79, at the trial, she was surprised how ordinary he looked, like any old man.

“That’s the troubling part,” she said.

Schwammberger was sentenced to life in prison in Germany and died there in 2004 at age 92.

Sam Nussbuam was transported to Auschwitz from the ghetto.

“From there, he went to work camps, to coal mines,” his daughter said. “He tells a story of how he was going up and down the stairs of this coal mine. There were people with no strength. They were all under-nourished and sickly. He tells how he tried to pick up a couple of people who were fallen, and try to save them, because they would have been shot otherwise.”

Don’t ask why

A 1971 quote from survivor Charlotte Delbo, the late French writer who wrote a memoir about her imprisonment in Auschwitz, ends the Union Station exhibit. It is printed on a wall near the exit:

“You who are passing by

I beg you

Do something

Learn a dance step

Something to justify your existence

Something that gives you the right

To be dressed in your skin in your body hair

Learn to walk and to laugh

Because it would be too senseless

After all

For so many to have died

While you live

Doing nothing with your life.”

Elizabeth and Sam Nussbaum went on to have a good life. They arrived in Kansas City in 1948 and would have four children: Larry, the physician, Mel, who followed his father into plumbing and started his own business; David, a rabbi; Bonnie, the attorney. They would have grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Some survivors of the Holocaust lost their faith along the way, wondering where God was as millions were exterminated.

Elizabeth Nussbaum prays every day now as she prayed every day then. She doesn’t know why she lived while countless others were killed. She didn’t expect to live.

“No,” she said flatly.

She credits God and chooses to believe that perhaps, having lost her entire family, she was meant to survive to have another. But asking the why, she said, is a useless exercise.

“That is a question you shouldn’t ask,” she said, “because there is no answer to that.”

Nussbaum has an artifact of her own. Eighteen years ago, she returned to Poland and to Auschwitz-Birkenau. She took a stone from the tracks that brought her and her family on the train.

She hired an artist to paint a rendering of the camp on the stone, along with the slogan that appeared above an entrance to the camp: “Arbeit Macht Frie,” loosely translated as “Work sets you free.”

“What a lie,” Nussbuam said, cradling the stone. “If this stone could talk, the stories it could tell.”