Nancy Baranet – Tackling the Tour de France predecessor that redefined women’s racing in 1956

From March 6-12 - conveniently coinciding with International Women's Day on March 8 - Cyclingnews is excited to welcome our readers to Women's Week, in which we'll be running a series of exclusive interviews, features, blogs, tech, advice and more.

The upcoming second edition of the Tour de France Femmes avec Zwift, featuring eight consecutive days of road racing in France, follows the format created in 1956 when intrepid European women and an American national champion were expanding traditional boundaries. The event showed women were capable of competing in stage races. That strengthened a campaign that culminated with the Union Cycliste Internationale introducing the women’s road race in the 1958 UCI World Championship program in Reims, France, paired with track championships in Paris.

In July 1956, Nancy Neiman Baranet of Detroit rode as the lone American in the eight-day Criterium Cycliste Féminin Lyonaise-Auvergne in hilly central France. “There were eighty-seven of us on the start line,” said Baranet, now ninety, on the phone from her home in Deland, Florida. “There were national teams from England, France, Belgium, Switzerland, and Luxembourg, and there were independent teams from the same countries. I was as independent as they came. I was the only American.”

Her independence came at a high price—she paid all her expenses under stringent true-blue Amateur Bicycle League of America rules. Her summer of racing in France and England, her second excursion to both countries, carried financial risk: “Each time I travelled abroad, I quit my job to go race, then reapplied when I returned.”

Baranet rode when Detroit led the world in design and mass production of cars and trucks. Car-centric nicknames of Motor City and Motown ignored its women cyclists who practiced the fine art of speedy wheels that dominated national cycling championships. In 1953, General Motors caused a hoopla for introducing the Corvette as a trendy two-seat luxury Chevrolet sports car with leather bucket seats to rival imports like MG, Jaguar, and Porsche. That summer at the ABLA nationals in St. Louis, Baranet of the Spartan Cycling Club upset her cross-town adversary and defending national Girls’ champion Jeanne Robinson Omelenchuck of the Wolverine Sports Club.

Read more

La Grande Boucle, La Course and the return of the women's Tour de France

Marianne Martin: Remembering the magic of the 1984 women's Tour de France

Nostalgia and celebration - Women's Tour de France pioneers reunite in Paris

The pioneers of women's cycling

International Women's Day: 7 remarkable women who made their mark on cycling's history

Each year ABLA nationals—on one-speed, fixed-gear bikes—rotated to a different city around the country in an August weekend of events called omniums, mock Latin for omnium gatherum, a collection of people and things, such as packs of racers battling over short distances. Entrants qualified the month before by medaling in state omniums. Divisions consisted of the Men’s Open for ages seventeen and up, with four events from one mile to twenty-five miles; Junior Boys, sixteen and under, in three events up to ten miles; and Girls, for females of all ages in three events up to five miles. Points awarded to top-five finishers determined division results.

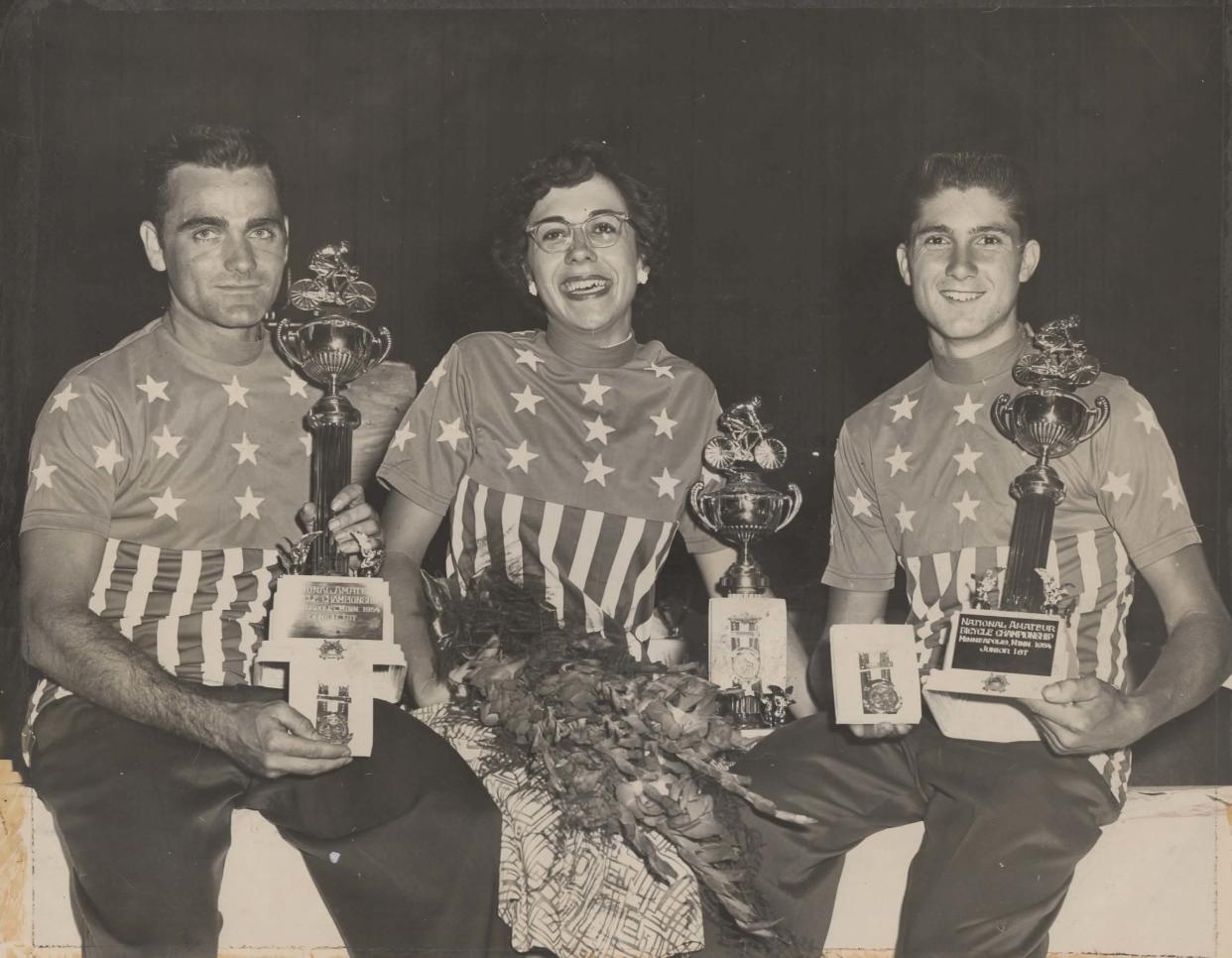

At the 1954 ABLA nationals in Minneapolis, which began with disastrous crashes on a high school cinder running track before events moved to a circuit on streets, Baranet won her second Girls’ national title. “I told the ABLA officials that I was twenty-one and was no longer a girl,” she said. The ABLA had introduced the Girls’ division in the 1937 omnium in Buffalo. Fifteen-year-old Doris Kopsky, daughter of Joseph Kopsky, who took home a bronze medal from the 200-mile 1912 Stockholm Olympics road race, won the Girls’ title, which continued till Baranet called for change. “And it was, to the Women’s National Champion.”

Nancy Neiman Baranet, with chestnut-brown curly hair trimmed short, stood five feet two. She grew up in a middle-class household with firm convictions. Her father, Allen Neiman, taught at the Henry Ford Trade School in Dearborn. Her mother, Mayme, was a homemaker for their two daughters. Older sister Suettta liked dressing up, while Nancy preferred playing outside.

After graduating from high school, Baranet joined an American Youth Hostel two-week cycling trip up and down Vermont’s Green Mountains and around Cape Cod on coastal Massachusetts, supervised by Louise Portuesi. Her husband, Gene Portuesi, was forming the Spartan Cycling Club to coach racers and challenge Detroit’s renowned Wolverine Sports Club.

“I had a taste of nipping at her heels on various climbs in the Green Mountains,” Barnet said. Upon returning to Detroit, she joined the new club and received a schedule for training.

Burning with ambition

Gene Portuesi, a Detroit native, had lived as a teenager in the early 1930s with his parents and grandparents in Nice, in the south of France. He liked hanging around a family-owned bike shop that made Urago bicycles. When the Tour de France swept through Nice, he joined crowds standing on the side of the road waiting more than an hour to cheer the ceremonial procession of publicity floats followed by eye-catching bright jerseys of riders cruising in the peloton and a long line of support vehicles—all bowling through like a circus on wheels.

In 1936 his family moved back to Detroit. He brought a Urago bike with him and won Michigan state championships in 1938 and 1939, but he lacked the money to represent Michigan in ABLA omniums in Chicago and Columbus, Ohio.

Portuesi held a management position at Ford when he left in 1945 to run his Cycle Sport Shop on Michigan Avenue. He imported Urago bicycles and European cycling gear, hard to find in America, and created a much sought-after mail-order business. When Baranet joined his Spartan Cycling Club, she encountered a short temperamental man with a thick mat of dark hair and a broad chest that gave him a square-shaped torso.

He drew her attention for coaching Michigan state champion Doris Travani Mulligan, winner of four straight national championships through 1950. Mulligan had retired from racing to marry and start a family. She exemplified being a champion—what Baranet described as the sum of many factors, chief among them discipline, a determined inner drive, and a tremendous ego—rather than settling for being good.

Baranet followed Portuesi’s winter regime of sit-ups, trunk twists, and other callisthenics, studying a new book on exercise physiology; and pedalling indoor training sessions on stationary rollers. He invited a state weight-lifting champion to create a regimen of arm curls, deadlifts, and military presses. She described Portuesi as scouring newspapers and magazines for reports about advances in sports science while overseeing his proteges so intently for ways to improve that his blood pressure never seemed to fall below 200.

For two years, she attended the Detroit Business Institute, taking classes in stenography, typing, and business. After graduation, she worked as a secretary for a general contracting company that constructed big office buildings. She usually pedalled to work and changed into office clothes.

One day she zoomed on her bike up the office drive when her wheels plopped into fresh-poured cement. She toppled over in full view of people in surrounding tall office buildings. “My feet were strapped on the pedals in true racing fashion, and for six weeks, I kept picking mortar off my bike and out of my ear,” she wrote in her memoir, The Turned Down Bar.

As soon as the weather allowed, she joined Spartan clubmates in group rides on Belle Isle, an island park flat as an airport runway, poking up in the middle of the Detroit River where car traffic was light in the mornings. Spring training featured sprint sessions on Tuesdays and Thursdays and an early-morning ten-mile individual time trial on Sundays.

Their sprints emphasised jumps—bursts of out-of-the-saddle acceleration, hands pulling up on the handlebar drops like a car mechanic lifting an engine from under the hood—to reach top speed as soon as possible before sitting on the saddle to spin legs fast in all-out dashes for the white finish line, repainted on the road every spring. “Without a jump, the fastest rider in the world is like a car running on kerosene,” Baranet said.

Detroit lacked a cycling track, so she and clubmates climbed into cars and drove 350 miles to Kenosha, Wisconsin, home to the Washington Park Velodrome for ABLA races. “It was the only banked velodrome operating then. We would leave the night before a race, stay in some horrible hotel in Chicago, get up early, and go race. Prizes weren’t the reward—just getting to use the site was.”

She made her ABLA national omnium debut in New Brunswick, New Jersey, in 1952. Then she finished second to Jeanne Omelenchuck, a Wayne State University graduate scoring her second gold medal with a diamond chip in the middle. California state champion Gay Juner—wife of Oscar Juner, a former six-day racer and a legend on San Francisco’s Bicycle Row—took the bronze medal.

In two seasons, Baranet rose from a novice to national class. She burned with ambition.

Seeking parity

In 1955 the Ford Motor Company launched its two-door Thunderbird, a leap from Ford’s boxy passenger cars with bench seats, to join Corvettes in the market against European sports cars. That same year Baranet looked to compete across the Atlantic. She wrote a letter on a manual typewriter and sent it via airmail to Eileen Gray, a retired racer in London with international experience.

Gray had founded the Women’s Cycle Racing Association promoting the cause of women’s racing when the men’s road and track races took up the lion’s share of attention. Like earlier suffragettes seeking the right to vote for women, Gray had a vision—she sought parity with the men’s races. She pressed for women to have in their own road and track divisions in the annual Union Cycliste International annual world championships. Gray organised a three-month itinerary for Baranet, beginning in May, on tracks in England and Paris.

“I flew British Airways to London,” Baranet said. “When we landed, the pilot said there was a small delay. I saw a ramp come up to the front entrance door, but I wasn’t paying much attention.” Over the intercom, the pilot asked for Baranet to stand up. “I nearly fainted.”

Down the aisle strode a dignified forty-year-old woman in a trim dress. Baranet recognized her from English cycling publications. “Eileen Gray had the plane halted so she could advise me that the bicycle frame builder Claud Butler wanted to present me with a track bike frame, which was okay except that I had to cover up the name on the plane or I’d be in deep doo-doo and lose my amateur status.”

After Gray left, the pilot drove to a parking spot near the terminal. “Everyone looked at me like I was some bimbo. Imagine what it was like—280 passengers had to wait for me to deplane while I was holding a covered bike frame.”

Baranet’s presence on the outdoor Herne Hill Velodrome in south London, as revered in English cycling as Boston’s Fenway Park in Major League Baseball, attracted the cycling press. (Black-and-white images of Baranet in her champion’s Stars and Stripes silk jersey are on the internet.) In May in Manchester, on the eponymous Manchester Velodrome, she tied the women’s world record for 200 metres, 14.4 seconds, set by Daisy Franks of England. Baranet also raced in Paris, on the Municipal Velodrome and on the pink concrete of the Parc des Princes Velodrome, where the Tour de France finished every year since Le Tour’s start in 1903.

Women’s racing got an astounding publicity boost while she was on the Continent. Isabel Best, in Queens of Pain: Legends & Rebels of Cycling, cites that women’s road racing was only beginning. Countries were recovering at different rates from the destruction inflicted in World War II. England survived the 1940 German Air Force bombardment but rationed food and gasoline for fifteen years; in the absence of sugar, tea drinkers substituted the artificial sweetener saccharin. Only a few national federations held road race championships.

In July 1955, during the Tour de France in cycling-mad France, a three-day road race for women called the Circuit Lyonnais-Auvergne got underway, the first French stage race ever for women. It was unofficially touted as the Tour de France Féminine.

Eileen Gray shepherded a six-rider national team in jerseys emblazoned with the Union Jack flag on the front. Millie Robinson, a soft-spoken thirty-one-year-old truck driver from the Isle of Man, won three forty-four-mile stages for overall victory. Three teammates finished in the top nine. They crushed the favoured French team.

When Baranet prepared to return to Detroit, she heard talk of another French stage race the next July. She gave back her Claud Butler frame to Gray and said she wanted in. Baranet also joined Gray in writing letters to UCI officials in Geneva, Switzerland asking them to add women’s racing to the world’s program.

Baranet flew home intending to race in the ABLA national championships in New York City. Portuesi suggested she rest from the strain of her overseas racing and international travel. But she was determined to pursue her third title for a hat trick.

The nationals took place around a flat asphalt half-mile track. State flags hanging on poles along the finishing straight represented the states of contestants. The three women’s events turned into a two-rider race, recalled Alice Springer Disney of the Wolverine Sports Club and runner-up to Baranet the previous year.

“Nancy and Jeanne were battling one another,” said Springer, now living in Discovery Bay, California. Jeanne Omelenchuck edged Baranet for the crown. Springer finished third—completing the second consecutive sweep by Detroit women.

Baranet had to wait another year to try for her third title.

Road to Roanne

In 1956 as Elvis rocked the world with hits like “Heartbreak Hotel” and “Don’t Be Cruel,” Baranet received an airmail letter in March from France. Marcel Leotot, director of the eight-day Criterium Cycliste Féminin Lyonaise-Auvergne in July, sent her an invitation.

“The limited activity in the United States and boredom of previous easy wins urged me to try my hand at road racing,” she said. “I telephoned my coach with the fantastic idea and assured him I would comply with every detail on any program he might fashion, thereby committing myself to the most gruelling, most rewarding experience of my career in racing.”

Baranet flew Air France in late June to Orly International Airport outside Paris. Portuesi arranged for a representative of Rochet Cycles, one of France’s oldest marques, to have a state-of-the-art ten-speed road bike waiting for her. Nevertheless, she took spring-steel toe clips to fit her small feet and her comfortable old leather Brooks racing saddle.

A train took her 250 miles southeast to Roanne, the size of Ann Arbor, Michigan, although Roanne sits in a mountain range. Her race started in two weeks in Roanne, the hometown of race director Leotot, the city’s utility manager. He booked her a room in the Hotel de France, lodging all teams. He hosted her to dinner with his wife and three young daughters.

“What amazed me was that while his front yard had huge piles of commercial coal, which had been unloaded from inland freighters for use in local industry and residences, his house was spotless,” she said.

Leotot was medium height, clean-shaven, with blue eyes and dark hair. He smoked Gauloises like they were his sixth finger. “He had an outgoing personality, very kind and caring, which I found charming.”

He took her and a group of other women riders on a drive to check out the towns and countryside of four of the eight stages. Many roads winding through the hills were barely wide enough for a single car. Baranet realised she had to ride in the first half of the pack to reduce her chances of crashing. She had a couple of weeks of training rides to break in her new bike, negotiate tough climbs and descents, and steel her mind to hang on every day.

One Friday morning, a mechanic told her that Stage 9 of Le Tour would pass eighteen miles outside Roanne. She pedalled her bike while he drove his motorscooter to a spot on a hillside providing a panorama. The early entourage that passed them involved an hour of cars and trucks advertising wine, toothpaste, and soap. Some trucks carried dancing girls and musicians.

An announcing truck whizzed by, a siren screaming, a light flashing. Fifty feet behind streaked Roger Hassenforder, a Frenchman hunched over and hammering his pedals to a solo stage victory. Two minutes later, more than 100 riders snaked past, followed by car upon car carrying managers, trainers, spare bikes, and equipment.

“The actual bike riders came and went like a puff of smoke,” she said.

She returned to Roanne for lunch, then accompanied Leotot to welcome Eileen Gray and a dozen British riders at the train station. Baranet greeted Gray and many friends she had raced against at Herne Hill.

On Saturday, July 14, Bastille Day, a national holiday, Leotot called everyone into the hotel lounge to brief them on the rules of the eight-day race starting the next day. Every stage commenced at 3 p.m., except the individual time trial, which began at 8:45 a.m. There were prizes for winning sprints into each town, signalled by a man standing by the side of the road waving a red flag to signal the finish line 200 yards ahead. The Queen of the Mountains award was based on points to the first five riders up small mountains and ten riders up big mountains.

An experience to never forget

Sunday, July 15, dawned humid and sunny. That afternoon Baranet pinned No. 14 to her white silk jersey, bands of red and blue circling her torso, USA printed front and back. She stood holding her bicycle in historic St. Germain-Laval for Stage 1, forty-six miles to St. Etienne.

Her name boomed in French over the loudspeakers: Non-cee Nee-mon, Ouuu-ess-ah (USA), sounding like no one she knew. She joined the biggest field of her career for her first road race. Publicity trucks drove up the road as the contestants stood for the French National Anthem, La Marseillais. Then race director Leotot, in shorts and sunglasses, sat on the back of a small motorcycle on the side of the road. His driver blew a whistle to start the action.

“That first stage separated the do-hards from the die-hards,” Baranet said. “When we hit the hills, we broke into smaller groups. Did I ever suffer! I had absolutely no experience in road racing and mountain climbing. At the base of the climbs, I started at the front of the pack and then lost places as we went. The longer the hill, the more I lost on the leaders.”

She crossed the finish line in St. Etienne in twenty-second place, seven minutes down on the stage winner and new race leader, Lyli Herse, small and slender. Herse had arms as thin as a Degas ballerina, diverting attention from powerful legs and a fierce drive. She was twenty-seven and embarking on a decade reign as French national road champion. Herse earned the Queen of the Mountains jersey and kept it to the finish.

When talking of Herse, Baranet’s voice softened: “Lyli had a sweet, charming personality.”

Barnet’s legs felt like rubber balls on yo-yo strings. She dug her luggage from the bus and headed to the shower in a school. “I was unable to close my hands to grasp tight and had to put my bag on the bike and walk it to the shower. The shower was like a gift from God.”

The second stage, forty-four miles, went from St. Etienne to Montbrison, popular for blue cheese. Approaching every hill, she moved up to the top three positions, then sacrificed places to stay in the cocoon of the pack. She recovered on the flat run into Montbrison and sprinted to finish fifth—behind Herse and English ace Millie Robinson. Baranet rose in general classification based on total elapsed time to sixteenth place.

Stage 3 went forty miles from Montbrison to Thiers, the knife capital of France. On the road, Baranet struck up a friendship with Millie Robinson. “Millie was fantastically built, with legs showing fine definition, a trim torso, and powerful arms. You merely had to look at her to know you’d better move yourself down another notch in the final place standings. She looked like an angel with a clear complexion, naturally curled hair, and a soft voice.”

Baranet had sweat running down her face, arms, and legs when her rear tire blew. She swerved from the pack, braked to stop, jumped off her bike, flipped her Campagnolo quick release, and pulled the wheel from the frame. A mechanic came to her aid, helped her mount a spare tire, filled it with a compression cartridge, and clamped the wheel back in the frame. Baranet time-trialled on her own. She dropped to seventeenth place overall.

Luxembourg’s curly-haired Elsy Jacobs had crashed and suffered deep road rash on arms, legs, and torso. Riders were billeted in a high school with a huge room filled with cots and mats. “All night long poor Elsy cried, moaned, and rambled,” Baranet said. “We took turns taking her to the toilet area—concrete pads in the round cement hole in the floor. We gave her enough aspirin to kill a mule. The next morning, she was at the starting line, all bandaged.”

Jacobs’s fall shredded her red-white-and-blue jersey and damaged her bike. Eileen Gray loaned her an English team jersey and a spare bicycle.

Stage 4’s fifty-mile course from Thiers over undulating roads finished in Riom, founded in the tenth century. Baranet misjudged her sprint too early and stayed the same in overall standings.

Stage 5 was the individual time trial of twenty-five miles from Riom to Randan. Riders arranged themselves in their starting order—beginning in reverse order of overall standings, and they went off in one-minute intervals.

Director Leotot pulled up on his motor scooter and singled out Baranet, Switzerland’s Mary-Louise Vonaraburg, and France’s Pirette Soupizet aside for wearing silk jerseys. International rules prohibited silk jerseys in time trials, based on their reduced wind resistance compared with wool jerseys. Eileen handed them green-and-white Women’s Cycling Association wool jerseys.

Baranet took off during a light rain. She overtook three riders, but the final three miles veered uphill, and she strained at her limit to pedal through the last two miles. When she crossed the finish line, she was too tired to get out of the rain and sat at the curb, panting while steam rose from her jersey.

The time trial scrambled overall standings. Three English women emerged as the top three overall, including Beryl French, a dark horse, as the new leader, Millie Robinson in second. Herse held fourth. Baranet stood seventeenth among sixty riders remaining.

Stage 6 went forty-five miles through a chilly rain, fog, and mist from Randan over mountains back to Thiers. To stay warm, Baranet pulled her jersey over a sweat shirt and inserted a newspaper sheet between them to block the wind. Her legs felt a little stronger. She finished thirteenth, holding seventeenth place among forty riders.

Stage 7 was the longest, fifty miles from Thiers back to Roanne on a sunny warm day. Baranet stayed near the front of the peloton. Spectators lined the roads from the outskirts of Roanne. With 200 yards to the finish banner spanning the road, Baranet blasted into the lead, but Robinson whipped around her in the last fifteen yards, leaving Baranet in second.

“I felt I had credibly represented the U.S.A., she said.”

Stage 8 involved a hilly forty-seven-mile circuit starting in Le Coteau, on a bank of the Loire River opposite Roanne and finished in front of Leotot’s house on Quai du Bassin. Crowds lined Roanne’s streets and cheered. Baranet sprinted to ninth place. She completed the event in fourteenth place, ahead of Elsy Jacobs.

Millie Robinson abandoned in the final miles when her rear derailleur broke apart. Her teammate Beryl French won overall, with Lyli Herse in second.

Baranet called the race a wonderful adventure. “Getting to the finish with the lead riders was an experience I will never forget.”

That, however, was not the end of the French adventure. Jeanne Robinson Omelenchuck flew in to join Baranet in Roanne. Leotot arranged for them and most of the finishers of his event to race in a series of criteriums. In the Paris suburb of Châtillon, in a thirty-four miler of twenty-five laps, Baranet whipped around Elsy Jacobs and French sprinter Pirette Soupizet for first place—making her the first American woman to win a French criterium.

Baranet returned to Detroit. Later, at the ABLA nationals in Orlando, Florida she duelled against Jean Omelenchuck to win her third national championship. In 1957 Baranet won her fourth crown in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

She became engaged to her weight coach, Nicholas Baranet, Jr. They married in May 1958. She retired from racing after finishing third in the 1958 nationals in Newark, New Jersey.

In August 1958 the UCI introduced its women’s world road racing championship in Reims, famous for its champagne. Elsy Jacobs charged over the finish line to win by two minutes.

Baranet was inducted into the U.S. Bicycling Hall of Fame in 1992.

Sheila Young Ochowicz, another Detroit cyclist and winner of three world match-sprint championships, credits Baranet as an advocate and voice for women’s cycling. “That was profound and worth recognition and respect. She had a great impact on the sport in helping develop opportunities for women in cycling.”

Please consider subscribing to Cyclingnews to support our women's content