Young people. New citizens. The fed-up. Trump campaign listed them as ‘deadbeats’ in 2016

Teresa is a 60-year-old Bolivian immigrant who works at a logistics company and raised two children.

But in the eyes of Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign she was a “deadbeat.”

That’s how the campaign categorized people who voted infrequently and didn’t have strong political views, according to internal data exclusively obtained by the U.K.’s Channel 4 News and shared with the Miami Herald.

Roughly 75,000 potential voters in Miami-Dade County — 5% of the people in Trump’s data — were classified as deadbeats, a Herald analysis found. It’s not clear how the campaign’s algorithm decided to label people. It used data points that included voter records from the Republican National Committee, political donor lists, and commercial databases that include things like where someone was born, what magazines they subscribe to and what kind of car they drive.

The Herald analysis found that “deadbeats” tended to be younger, perhaps reflecting a limited history of voting or a tendency to move from state to state, and were also more likely to be Hispanic or Asian than Black or White.

Some, like Teresa, who didn’t want her last name used, were newly minted citizens. Others were just fed up with politics.

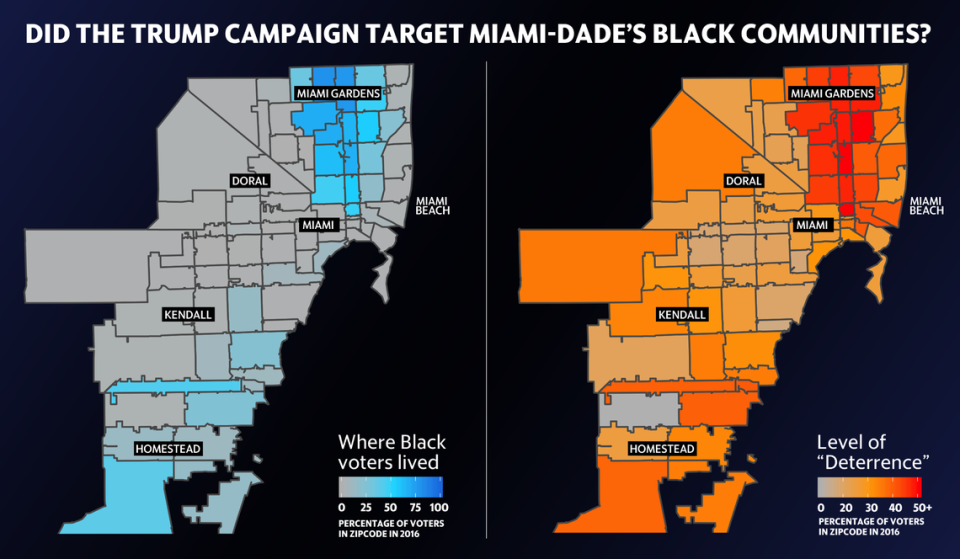

These deadbeat voters, the campaign decided, were not worth the time and money necessary to micro-target them with online advertisements to persuade them to vote for Trump — or to sour them so much on Hillary Clinton using negative ads and disinformation that they decided not to cast a ballot at all. (The campaign called that latter category “deterrence.” Although all presidential campaigns collect and organize big data to segment voters and allocate resources, critics said the “deterrence” category suggested voter suppression, especially because it disproportionately affected Black people.)

For this investigation, the Miami Herald partnered with the U.K.'s Channel 4 News, which exclusively obtained a 2016 Trump campaign/Republican National Committee voter database. See Channel 4 News' reporting on "Deterring Democracy."

The 2016 election was Teresa’s first time casting a ballot as an American.

She ended up voting for Trump and will do the same in 2020

It’s not that she likes him very much but, she believes, “he’s the [only] one that’s going to stop all these socialists and dictators.”

Susan MacManus, a professor emeritus of political science at the University of South Florida, said the term deadbeat reflected “cynicism” about voters who weren’t regulars at the polls.

“It’s very unbecoming to the political process, but it permeates society as well. Just spend two minutes on Twitter,” MacManus said. “There are so many people that are alienated from politics because of it.”

And it reminded her of the infamous moment when Hillary Clinton said many Trump supporters belonged to a “basket of deplorables.”

“There is equal opportunity for being crass,” MacManus said.

Alicia Batista was understandably defensive when a Herald reporter told her she had been labeled a deadbeat.

“No way,” said Batista, who was born in Cuba and gained American citizenship in 2015. “I’ve voted [every time] since I became a citizen.”

But the Trump campaign was generally right that deadbeats would vote at low rates.

Just 45.5% of Miami-Dade voters categorized as deadbeats went to the polls in 2016, compared to an overall county turnout rate of 67% for voters in the campaign’s database. Only voters labeled as “disengaged” Clinton supporters had a lower turnout than deadbeats.

“Deadbeat are people who don’t vote or have an opinion,” Trump’s chief data scientist Matthew Oczkowski said at a data conference in 2017 as he explained the campaign’s terminology. The crowd responded with laughter.

Oczkowski is working for Trump again in 2020.

Tim Murtaugh, a campaign spokesman, did not respond to a request for comment when asked if the president’s team was again categorizing voters as deadbeats.

In 2016, the campaign worked with the controversial British data firm Cambridge Analytica, now defunct, to divide voters into categories like “persuasion,” “deterrence,” “core Trump,” “core Clinton,” and “deadbeats.”

‘Pick your poison’

The deadbeats skewed young.

More than 7% of Miami-Dade voters under 35 were labeled deadbeats, compared to 2.4% of voters 75 and older.

Millennial Javier Acevedo, 31, has never voted in his life.

2020 won’t change that.

“Right now the majority of the ads are about Donald Trump being racist, which I agree, and Joe Biden ruining the economy, which I agree,“ Acevedo said. “It’s like, pick your poison. So I’d rather not pick either.”

Roughly 7% of Asians and Hispanics were categorized as deadbeats. Black voters were the least likely to be placed in that category; one-in-two Black voters were instead selected for deterrence.

While deterrence was heavily concentrated in Black communities, deadbeats were more evenly spread out across the county.

People the Trump campaign thought were Puerto Rican were more likely to be listed as deadbeats than Cuban Americans, a crucial GOP constituency.

Venezuelan Americans and Uruguayan Americans were the most likely Hispanics to be categorized as deadbeats. More than 10% of Uruguayans and Venezuelans were categorized as deadbeats.

The Trump campaign’s data generally labeled Miami-Dade Hispanics as Cuban, Puerto Rican, or Mexican, but it got many of those assessments wrong.

The Herald was able to determine the real place of birth of nearly 156,000 people in the data using voter registration records compiled by Dan Smith, a political scientist at the University of Florida.

New voters

Deadbeats were more active voters in 2016 than they had been four years earlier.

In 2016, a higher proportion of voters categorized as deadbeats voted than in 2012, the Herald analysis found. Their participation rose by 3.6 percentage points.

The only group that saw a bigger rise in participation compared to 2012 were voters labeled as “disengaged” Trump supporters — apparently not so disengaged after all. Turnout remained flat overall for voters in the campaign’s data.

Despite being called a deadbeat, Nicholas Acosta cast a ballot in 2016. He doesn’t remember for sure who he voted for but thinks it was Libertarian candidate Gary Johnson.

Acosta still hasn’t made up his mind for 2020..

The 25-year-old tuned into the most recent presidential debate. The squabbling turned him off.

“It was like watching kids in high school arguing,” Acosta said.

Miami Herald staff writers Christina Saint Louis and Ana Claudia Chacin and McClatchy DC staff writer Shirsho Dasgupta contributed to this report.

This story was researched and written using a 2016 Trump campaign/Republican National Committee voter dataset obtained by Channel 4 News in Great Britain and shared with the Miami Herald. The two news organizations consulted with each other and shared information but produced their own reports.