Why Ice Climbers and Skiers Do Not Experience The Same Avalanche Risk

This article originally appeared on Climbing

Years ago, in October, three keen ice climbers made the long approach to the Lowe Route (V WI 4+) on the north face of The Sphinx, in Montana. The long ice route appeared to be formed, the winter snowpack had only begun to build, and the climbers didn't think they would have to contend with any avalanches that day. No one packed a shovel, beacon, or probe.

Near the start of the gully, one person paused to tie his boot while the others continued higher, breaking a deep trail. Deep into the gully, the pair triggered a small slab avalanche that swept them off their feet; not enough to bury them, but enough to hurtle them down the snow slope. The third person, tucked off to the side while tying his boot, watched in horror as his friends tumbled down a sizable cliff. Neither of them survived.

"If you look at the statistics in the Canadian Rockies, ice climbing is way riskier than skiing with respect to avalanche hazard," said Grant Statham, avalanche forecaster and search and rescue technician for Banff, Yoho, and Kootenay National Parks in Canada.

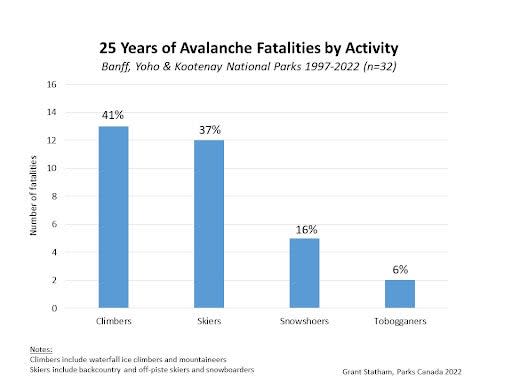

For the last 25 years Statham has kept track of avalanche-fatality statistics within these parks: 37% of avalanche deaths were skiers, while 41% were climbers. But, frighteningly, Statham estimated that there were at least 10 times less climbers than skiers recreating during this period, most of whom were killed by overhead, naturally occurring avalanches. As these statistics suggest, the way skiers and ice climbers experience avalanches are "Like two different worlds," Statham said.

These different experiences begin at the planning stage: Statham points out that ice climbers will always have fewer terrain choices than skiers because they must vie for a limited number of frozen drips. Skiers, in contrast, can make turns on nearly any aspect covered in snow. (Skiers can certainly be fixated on a line but they often have the option of bailing to a laundry list of Plan B's if their hoped-for conditions don't pan out.) "But with climbing, usually, when you decide you don't like it, you have to bail," Statham said. "It's not like you can [ice climb] all over the place."

This scarcity makes the "route selection" stage of planning incredibly important. Once climbers have decided to go for it, they are locked into that route for hours. Their precarity is further heightened by the fact that ice climbs often form in gullies, the very definition of a terrain trap. If an avalanche occurs it will likely bury any ice climbers recreating below.

Because of the terrain-trap nature of many ice climbs, small avalanches are far more deadly to ice climbers than they are to skiers. If an ice climber is traveling unroped between technical pitches, for example, a small slide can be enough to knock the climber off their feet and down a cliff. A slab avalanche can be as small as "your kitchen table" to have dire consequences, according to Doug Chabot, director of the Gallatin National Forest Avalanche Center.

"Ice climbers aren't dying because they got buried and we couldn't find them," said Chabot. "Ice climbers are dying because they whip a few hundred feet off a climb." Chabot said these avalanches do hit unroped climbers at inopportune moments, but they also have the strength to completely flush roped-and-anchored climbers down their route. Roping up, he said, is not an avalanche-mitigation catch all: ice climbers must be aware of avalanche risk in their planning stage and adapt accordingly.

Skiers have another advantage ice climbers do not: the ability to assess snow conditions as they ascend a slope. They gather data about storm and wind slabs with their poles, feel for whumping snow underfoot, and dig snow profiles to evaluate the cohesion of various layers in the snowpack. Skiers get to learn how the snowpack changes based on the elevation and aspect, and, critically, can make many of these observations from a lower-consequence zone.

Climbers, meanwhile, can leave their vehicle and in mere minutes be climbing beneath incredibly complex alpine terrain. In this scenario, according to the professional climber and ACMG alpine guide Sarah Hueniken, climbers are making an "educated guess" of whether or not a natural avalanche will bury their route that day.

Avalanche conditions typically vary depending on elevation, and for this reason, "it's important to look at all three of the levels [in the avalanche forecast], even if you're only climbing [below] treeline," said Hueniken. It is easy to feel safe in a thickly forested gully, but there could be a vast snowfield looming in the alpine.

Hueniken, and many other avalanche professionals, acknowledge that obtaining information about snow conditions far above you is guess work at best. And as your climbing day goes on those once-timely predictions can change: strong overhead winds can redistribute snow without any warning signs from within your protected cleft. Making the decision to continue climbing or bail while staring at the crux pitch above you, listening to the wind, is "like pure avalanche forecasting," Statham said.

Statham tackles this problem by simplifying it. He only climbs in big avalanche paths when the danger is moderate or low. But if he is mid-route and the wind starts blowing or heavy snowfall begins, Statham bails, regardless of how mild the avalanche forecast was for that day.

View this post on Instagram

"I think for climbers you almost have to simplify it a little bit, because it's really difficult to forecast natural avalanches from 2,000 feet above your head," Statham said.

Statham recommends gathering as much weather data as possible before going on the climb, and synthesizing this with the avalanche forecast. For example, if the avalanche problem is wind slabs, monitoring the weather station nearest to the ice climb for wind forecasts will be key. Hueniken also emphasized understanding what the terrain looks like above the ice climb as a part of avalanche risk analysis.

"For skiers we're always telling them to dig down and test, and for climbers [we suggest looking] up and look at the weather station, to try and figure out what's going on way above your head," said Statham.

Just as skiers do, Chabot advises turning around at any sign of instability, such as snow cracking on the approach, recent avalanche activity, or wind slabs that have not adhered well to the snow layers below. He also recommends carrying the basic safety equipment used in ski-touring culture: beacon, shovel, and probe.

Climbing with avalanche gear is not as uncommon as it used to be but, historically, taking a beacon, shovel, and probe up ice climbs was not in our culture. "I think the big difference is that we are so focused on going light and not wanting to carry anything extra with us," said Statham. Statham himself did not always take avalanche gear with him when he was a young ice climber. But after becoming a rescuer and working on avalanche accidents where the victims were not carrying avalanche gear, Statham changed his perspective.

"This [not carrying avalanche gear] really struck me as wrong and very hard on us as rescuers and the family members who want their loved ones back," said Statham.

Statham admits that it is more logistically challenging to carry all the avalanche equipment as an ice climber. You already have a backpack filled with climbing gear and belay clothing, and carrying a shovel and probe while leading the crux pitch is not ideal. Statham compromises by always wearing a beacon and ensuring it is out of the way while climbing; he keeps it tucked under his left arm in a chest harness or in a zippered pocket on the chest of his base layers. He will bring the rest of his avalanche equipment on a case-by-case basis.

"I look at that equipment much like you would look at the rack," Statham said. "So I like to have the conversation about what to bring and what not to bring with the partner every time."

For example, if there is a steep, snowy approach to reach the route, Statham and his partner would each carry a shovel, beacon, and probe to the base. If they plan to climb and rappel the route, they might leave the gear clipped to an anchor at the base. Or if he is climbing a route that includes walking on avalanche-prone slopes between pitches, he and his partner could have one set of avalanche gear between them and the second person would carry it, as it is more likely for the first person to trigger an avalanche. But every situation is different, Statham stressed, and the goal is to be light without sacrificing the correct gear.

Chabot keeps a beacon in his pants pocket and carries a lightweight shovel and snow saw that he only uses ice climbing. The snow saw allows him to dig a pit and make a few quick assessments about the snowpack on the way up. And if there is avalanche danger while climbing, Chabot wears a tiny backpack while leading that contains the lightweight shovel and probe. His whole kit weighs under two pounds.

***

A note from Sarah Hueniken: Over the last three years, myself and Grant Statham have worked with Avalanche Canada to improve their educational resources for ice climbers. We recently created the Ice Climbing Avalanche Atlas; an in-depth look at many classic ice routes in the Canadian Rockies that are located in avalanche terrain. Through surveying the public for their observations, and mapping the terrain above these climbs with high-resolution overhead images, ice climbers now have a historical and visual perspective of the avalanche hazard for these climbs. The current survey and finished Atlas can be found here: www.avalanche.ca/resources/ice-climbing/atlas

Keely Dickes is a freelancer writer based in Glenwood Springs, Colorado.

Also read:

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.