Whose NBA career is better? Patrick Ewing vs. David Robinson

Victors are determined decisively on the court, but one great joy of fandom outside the lines has no clear winner. We love to weigh the merits of our favorite players against each other, and yet a taproom full of basketball fans can never unanimously agree on the GOAT. In this series, we attempt to settle scores of NBA undercard debates — or at least give you fodder for your next “Who is better?” argument.

[Previously: Dwyane Wade vs. Dirk Nowitzki • Carmelo Anthony vs. Vince Carter • Kobe Bryant vs. Tim Duncan • Chris Paul vs. Isiah Thomas • Pau Gasol vs. Manu Ginobili]

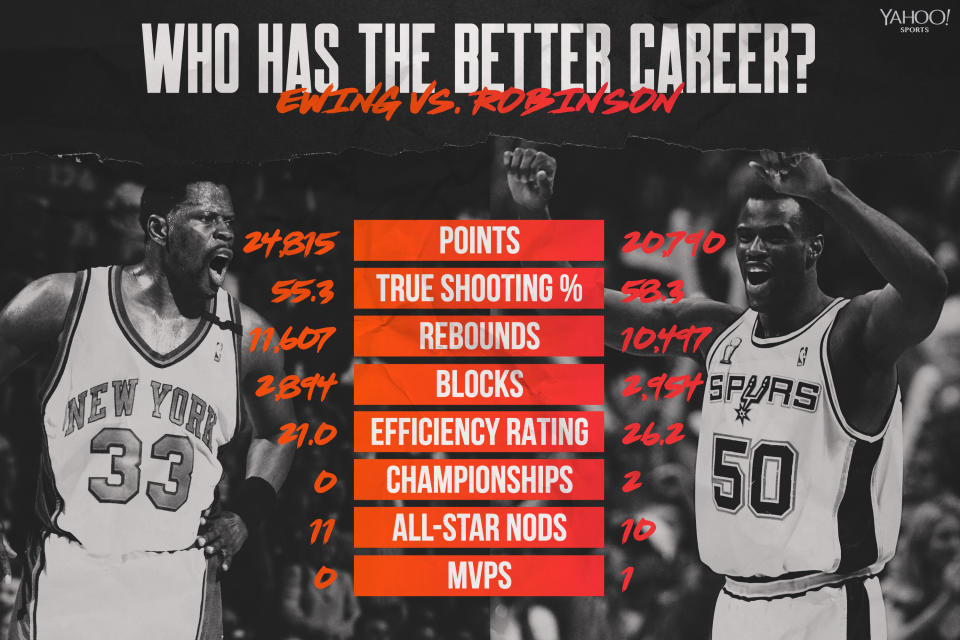

THE MATCHUP: Patrick Ewing vs. David Robinson

Prime numbers

Following a legendary four-year career at Georgetown that included an NCAA title and national player of the year honors, Ewing joined the New York Knicks as the No. 1 overall pick in the 1985 NBA draft (via a frozen envelope conspiracy theory?). He made an instant impact. Ewing participated in the All-Star Game as a rookie and proceeded to average 20-plus points every season until he turned 36 years old.

It was then, at the tail end of the last great Knicks team’s run, that due to wrist and Achilles injuries his career entered its precipitous decline, which infamously featured stops on the Seattle SuperSonics and Orlando Magic. For the first 13 years of his career — what we’ll call his prime — Ewing averaged 23.5 points (51.3 FG%, 74.4 FT%), 10.4 rebounds, 2.7 blocks, 2.1 assists and 1.1 steals per game.

In 13 prime seasons, Ewing made 11 All-Star and 11 playoff appearances, including a trip to the NBA Finals, another to the Eastern Conference finals, seven second-round showings and a pair of first-round exits. Knicks teammates Mark Jackson, Charles Oakley and John Starks each made one All-Star appearance in that span.

The height of Ewing’s career coincided with Hakeem Olajuwon’s prime and much of Robinson’s. Ewing was the First Team All-NBA center just once in that time — over Olajuwon on the Second Team and Robinson on the Third Team in 1990. He made the Second Team another six times (four times behind Olajuwon and twice behind Robinson). There was no Third Team All-NBA for the first three years of his career.

Robinson’s prime is harder to define. His numbers started to decline in 1998-99, two years after his back and foot cost him all but six games, but that slide can be attributed to the arrival of Tim Duncan (via those same injuries). Robinson earned Third Team All-NBA honors in 2000 and 2001, before his production fell far enough for the West All-Stars to carry only one true center (Shaq) for the first time in forever.

By this measure, from his rookie season to his final All-Star campaign, Robinson’s prime spanned 12 years, when he averaged 22.8 points (52 FG%, 73.9 FT%), 11.1 rebounds, 3.2 blocks, 2.7 assists and 1.5 steals from 1989-2001. The Spurs made the playoffs every season but the one completely derailed by injuries, including his first of two titles, two more West finals appearances and four second-round exits.

Robinson’s prime coincided with teammate Sean Elliott’s two All-Star bids and the first three of Duncan’s career. Robinson made 10 All-NBA rosters (finishing behind Ewing only twice in the 1990s), and he was the First Team All-NBA center on two occasions, including his 1995 MVP campaign. He finished top-eight in MVP voting on eight occasions to Ewing’s seven. Robinson also consistently finished ahead of Ewing in Defensive Player of the Year voting when both were in their primes.

Advantage: Robinson

Career high

Robinson’s peak is easier to nail down. Coming off a scoring title, when his season-ending 71 points nudged him ahead of Shaquille O’Neal, Robinson submitted his individual opus in 1994-95, capturing MVP honors as the lone All-Star on a 62-win team that succumbed to Olajuwon’s Houston Rockets in the conference finals.

At 29 years old, Robinson averaged 27.6 points on career bests of 53 percent shooting from the field and 77.4 percent shooting from the free-throw line. He added 10.8 rebounds, 4.9 combined blocks and steals, and 2.9 assists in 38 minutes per game. He also served as the First Team All-Defensive center that year.

The Spurs rode Robinson in the playoffs until their season ended in a six-game West finals loss to the Rockets. Although his shooting efficiency dipped, Robinson’s stats stayed fairly consistent throughout the playoffs and in that series, yet his line was still dwarfed by Olajuwon’s 35-13-5 with 5.5 combined blocks and steals.

Ewing has two peak seasons to choose from — individually as a 27-year-old in 1989-90 and as the best player on a 57-win team that took Olajuwon’s Rockets to seven games in the 1994 Finals. Ewing placed fifth in MVP voting both seasons.

Ewing captured his lone First Team All-NBA honor in 1989-90, averaging a career-high 28.6 points on career-best shooting numbers (55.1 FG%, 77.5 FT%). He added 10.9 rebounds, four blocks and 2.2 assists in 38.6 minutes per game. That team, featuring Oakley as its next-best player, won 45 games and lost the best-of-seven conference semis in five games to the eventual champion Detroit Pistons.

His true peak likely came four years later, when his production and efficiency slightly dipped across the board, but he anchored a Knicks team that came closer to winning a title than any other since 1973. He too got outclassed by Olajuwon, although less so, and we might remember Ewing’s playoff résumé differently if Starks had not gone 0-for-11 from 3-point range in Game 7 of those 1994 Finals.

Advantage: Robinson

Clutch gene

That’s the thing about Ewing: He is labeled a playoff failure. There’s an entire theory named after his postseason shortcomings. His teams made two trips to the Finals, the second of which came after Ewing suffered a season-ending Achilles injury in Game 2 of a 1999 Eastern Conference semifinals that the Knicks won in six games.

That team could have used Ewing opposite Duncan and Robinson in a five-game Finals loss, even if the 37-year-old’s double-doubles were hollower at that point. Robinson averaged 16.6 points (42.4 FG%, 68.8 FT%) and 11.1 rebounds in 37.1 minutes per game with Marcus Camby and Chris Dudley in the 1999 Finals.

Game 7 of the 1994 Finals marked the biggest night of Ewing’s NBA career. His 17 points on 17 shots, 10 rebounds and two blocks in 44 minutes made for a relatively underwhelming performance in a 90-84 loss made worse by Starks’ effort.

That Game 7 followed two more in the conference semifinals and finals, when Ewing posted monster numbers in narrow wins over the Michael Jordan-less Chicago Bulls and Reggie Miller’s Indiana Pacers. His 24 points, 22 rebounds, seven assists and five blocks in Game 7 of the 1994 East finals are all but forgotten.

In addition to the Starks debacle, there was the Charles Smith game, in which the power forward missed four straight chances to put the Knicks ahead in the final seconds of Game 5 in a deadlocked East finals. Ewing finished with a game-high 33 points, nine boards, three assists and (to be fair) six costly missed free throws.

In its place, we remember Ewing’s missed wide-open layup that would have sent Game 7 of the 1995 East semis into overtime against those same Pacers. (That erased Ewing’s stat line of 29 points, 14 rebounds, five assists and four blocks.)

For the most part, Ewing was the same beast in series-deciding games as he was throughout much of his career. In nine career Game 7’s (or series-ending Game 5’s), Ewing averaged 24.4 points (49.2 FG%, 71.4 FT%), 13.1 rebounds, 3.8 assists and 2.2 blocks. The Knicks finished 5-4 in those games, losing only to Jordan’s Bulls, Olajuwon’s Rockets, Miller’s Pacers and the Tim Hardaway-Alonzo Mourning Heat.

Ewing’s career playoff numbers compared to Robinson’s are fairly similar:

Ewing: 20.2 points (46.9 FG%, 71.8 FT%), 10.3 rebounds, 3.1 combined blocks/steals and two assists in 37.5 minutes over 139 career playoff games.

Robinson: 18.1 points (47.9 FG%, 71.8 FT%), 10.6 rebounds, 3.7 combined blocks/steals and 2.3 assists in 34.3 minutes over 123 career playoff games.

Robinson played a single Game 7 in his career — in his rookie year. He totaled 20 points on 21 shots, 16 rebounds and three blocks over 41 minutes in a 108-105 second-round loss to Clyde Drexler’s and Terry Porter’s Blazers in the 1989 playoffs.

Prior to Duncan’s arrival, Robinson’s playoff series record was 5-7. (Ewing’s career playoff series record was 16-13.) In his lone Duncan-less playoff series beyond the second round, Robinson also underwhelmed, bookending the conference finals loss to Olajuwon’s Rockets with 5-for-17 and 6-for-17 shooting efforts in defeat. He was stamped as too tentative on both ends in a potentially legacy-defining series.

The rings changed that. In two trips to the Finals with Duncan, Robinson averaged a solid 13.5 points (49.5 FG%, 69.2 FT%), 9.4 rebounds, 2.4 blocks and 1.5 assists in 31.5 minutes per game in a pair of decisive series victories. Still, it is hard to imagine, had one of the 10 greatest players ever joined the Knicks in 1994, when Ewing was entering his age 32 season, that he too would not have a ring or two.

Advantage: Ewing

Hardware

• Ewing: Eleven-time All-Star; seven-time All-NBA selection (1990 First Team, 6x Second Team); three-time All-Defensive Second Team selection; 1986 Rookie of the Year; 1985 National College Player of the Year; 1984 NCAA champion (Final Four Most Outstanding Player); two-time Olympic gold medalist

• Robinson: Two-time champion; 1995 MVP; 1992 Defensive Player of the Year; 10-time All-Star; 10-time All-NBA selection (4x First Team, 2x Second Team, 4x Third Team); eight-time All-Defensive selection (4x First Team, 4x Second Team); 1994 scoring champion; 1992 blocks leader; 1991 rebounds leader; 1990 Rookie of the Year; 1987 National College Player of the Year; 1986 USA Basketball Male Athlete of the Year; three-time Olympic medalist (2x gold, 1x bronze)

Even if we were to forget the rings on Robinson’s fingers, he would own a decisive edge in this category. His trophy case features an MVP award and Defensive Player of the Year honor where Ewing has neither. Same goes for Robinson’s scoring, rebounding and block titles. He appeared on nearly twice as many All-NBA rosters as Ewing, including four times as many First Team nods. It’s not really all that close.

Then, throw in the Larry O’Brien Trophies, and it’s a landslide. No amount of explaining how he got there can take those away from Robinson. It’s too bad Ewing didn’t land as Shaquille O’Neal’s backup on the Los Angeles Lakers in the 2000 four-team trade that sent him to the Seattle SuperSonics and Horace Grant to L.A.

Advantage: Robinson

For the culture

Both Ewing and Robinson were members of the 1992 Olympic Dream Team, a fact too often lost to the attention paid to Jordan, Magic Johnson and Larry Bird. The two centers went at each other in practice and alternated starts on that team. Ewing was fortunate enough to be on Jordan’s team in the blue-white scrimmage.

What I remember most about Robinson is his nickname, The Admiral, and the fact that he is the lone Naval Academy graduate to play in the NBA. He required a waiver to enlist at 6-foot-8 and grew another five inches. And he fulfilled his active-duty service before joining the Spurs two years after they drafted him No. 1 in 1987.

Robinson is perhaps one of the most underrated players in NBA history. His chiseled frame and the grace with which he moved made him appear invincible. Overshadowed by his complementary role on the first two of San Antonio’s five title teams is his assault on statistical norms prior to Duncan’s arrival. His career-high averages of 29.8 points, 13 rebounds, 4.8 assists and 4.5 blocks are all remarkable, and to be the best player on a team that won 60-plus games is no small feat, either.

But Ewing was larger than life upon entering the NBA as the No. 1 pick in 1985 in a way that Robinson was not. He had led Georgetown to three NCAA title games in four seasons, when that meant a whole lot more than it does now, playing in a trio of the most memorable games in college basketball history — losing to Jordan in 1982, beating Olajuwon in 1984 and upset by Villanova in 1985.

And he joined the Knicks in basketball-crazed New York, where they were desperate for a contender after a decade of mediocrity during the heydays of Bird’s Celtics, Magic’s Lakers and Dr. J’s 76ers. He was billed as the savior in the NBA’s biggest market, and while he failed to deliver a title, he headlined the rough-and-tumble era that was Pat Riley’s Knicks — a team built to make life hell on Jordan.

The 1990s Knicks were ultimately a foil, but they were a lovable one, and Ewing consistently found himself at the center of some of the game’s most historic battles.

Advantage: Ewing

THE DAGGER: David Robinson is better.

If you have an idea for a matchup you would like to see in this series, let us know.

– – – – – – –

Ben Rohrbach is a staff writer for Yahoo Sports. Have a tip? Email him at rohrbach_ben@yahoo.com or follow him on Twitter! Follow @brohrbach

More from Yahoo Sports: