'We're going through a death': Ex-ballplayers coming to terms with life after baseball

I was introduced to Ryan Kalish this winter at a place in Santa Monica, California, known for decent burgers and cold beer. I recalled he’d had more than a little promise as a player. I also hadn’t heard much of him for a while.

He was staying in the area with friends and he nodded toward a table where a handful of men and women were choosing chairs and hanging their coats. He said he wasn’t playing ball anymore and that he was teaching pilates and had a stake in a startup company called Birdman Bats. He seemed excited about both, and we agreed that a story about the bats, an enterprise that had begun with a single lathe in a garage in Northern California, would be worthwhile. His buddy, Lars Anderson, was a co-founder, he said, and for the second time that night I was struck by a name and career I knew existed but couldn’t quite place. He said Lars had played overseas in recent years but had retired as well, and that I’d like Lars, who was intelligent and funny and had an interesting way of looking at things.

The place was getting louder, my burger colder, my beer warmer, and we shook hands, promising to stay in touch. My 26-year-old son, sitting beside me, said, “Who was that?” A guy who used to play ball, I told him. “Used to?” he said. “How old is he?” I tapped at my phone. Thirty. I tapped again. Lars was 31.

Several months later, this time at a Thai place in an El Segundo, California, strip mall, Ryan recalled that night in Santa Monica and said, “Man, I was so rattled then.”

He looked at Lars, who smiled.

“Tell him about your routine,” Lars said.

“My routine?” Ryan said. “Oh, yeah. Wake up, cry, pilates, cry, cook, cry. It was like every day. Every single day. Listening to these songs that I, I actually wanted to flush it. You know, I knew it was happening. So I put on these songs that would kind of trigger it, just let it out. You know?”

It wasn’t exactly the baseball running out of him, but perhaps the since gone vision of who he’d be in baseball, what he would do in baseball, how the two of them -- the talented young man and the game, his game -- would have grown at least a little older together. Surely, by now, he’d have done great things, created greater moments, stood in body and soul with the player he’d always imagined.

Instead, a little more than a year ago, he’d talked himself into the spring training lineup of the independent New Britain Bees, asked his useless knee to hold for a few more minutes, flared a single, breathed that in and surrendered. The bat didn’t make it.

“Broken,” he said, “just like me.”

They were drafted by the Boston Red Sox in 2006, Lars nine rounds after Ryan. Lars was from Northern California. Ryan from New Jersey. They became friends late in that same summer in Fort Myers, Florida, and in the coming summers were road roomies and bus mates. Ryan reached the big leagues in July 2010, Lars about a month later. They were 22. The game they had played since they could hardly remember, since Christmas mornings meant toy bats and balls, since they’d begun to see they were maybe just a little better than the other kids, was only just beginning. Staying was the hard part, everyone said. Getting there, though, that was something, too.

Over parts of four seasons spread over seven summers, Ryan played in 153 major league games. If his swing and arm and foot speed and instincts were willing, and they were, his body was not. His knees, his shoulder and his neck took turns sending him to doctors and trainers and, eventually, a reality that his career would be those 153 games, and those would be surrounded by the sorts of experiences that has a man schedule into his day a good cry.

Lars played in 30 games over three seasons, all with the Red Sox. His first career hit -- a single against the Tampa Bay Rays at Fenway Park -- also saw the runner ahead of him turn recklessly at second base, get back-picked from right field and tagged out. So Lars stood at first base in the moment he’d worked his young life to experience while a full house booed Bill Hall. He’d get seven more big-league hits, then nearly a decade later strike out on a baseball field in Germany, pack his gear bag one more time and head home for good.

“I don’t have sadness or depression over my career as a baseball player,” Lars said. “I think I have more anxiety about what lies ahead. I’m not mourning not being able to play. I don’t even think about playing baseball. I played enough. I miss batting practice. For me, the sadness and the terror and the anxiety and the fear is more based on maybe the loss of identity. Just feeling like you’ve all of a sudden slipped into anonymity. You’re not relevant anymore. It’s like a certain death of this projection that you have of yourself. How people identify with you. Which is not necessarily healthy. ... I’ll get over that.

“But, I guess for me, the thing is, I’ve had one job my whole life. I’m sure some things will start to emerge. I’m interested in a lot of things. ... But this is a death. We’re going through a death. You don’t know what happens when you die. I’m in that period where it’s like, ‘Oh damn, I don’t know what’s coming.’ And that’s really scary.”

‘Twice as harder than hell’ to stay in the majors

Approximately 60 percent of players who log one day in the major leagues do not reach the service time required (about three years) for salary arbitration, according to Steve Rogers, the former major league pitcher who heads the Major League Baseball Players Association’s career transition program. The average major league career for those players, he said, is about 1 ½ years. Of the rest, the 40 percent who do play long enough to secure the financial gains of salary arbitration and beyond, the average career is 7 ½ years. Based on the union’s research, Rogers said, the average major league career is about four years.

Given minor-league salaries barely cover food and grooming products, and the major league minimum salary is less than $600,000, and most players do not finish college if they start it at all, the fresh-out-of-work ballplayer would seem particularly vulnerable in a job market that generally requires education, experience and, well, skills beyond hitting or throwing a fastball. The presumed path, perhaps, is a minor-league coaching job, if the game still runs deep enough and options are few. To that end, an entry level, A-ball hitting coach could expect an annual salary of about $50,000, and there’ll be plenty of competition for it, and that kind of money might be just enough to get a coach to his offseason job.

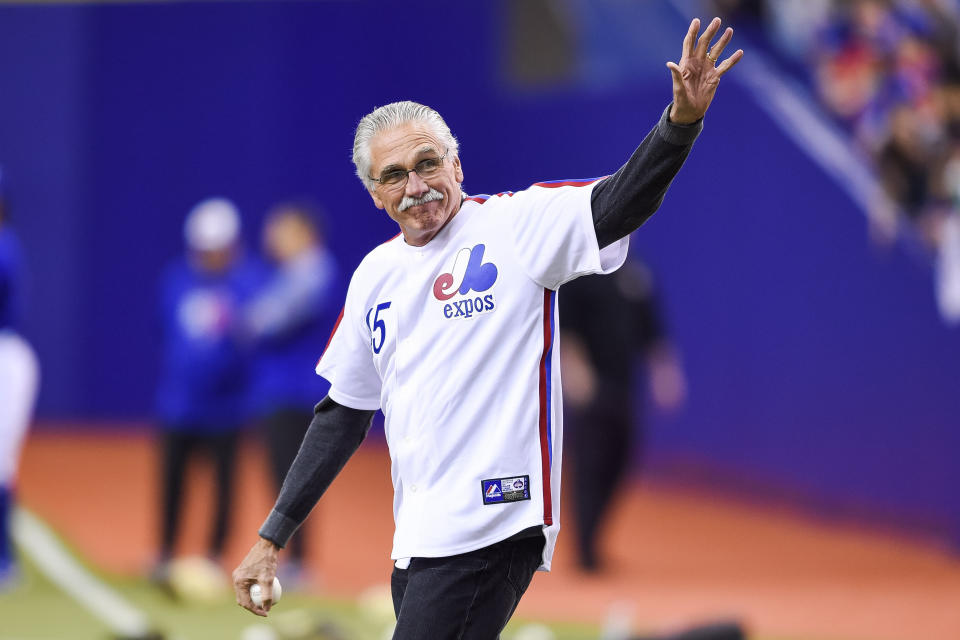

Steve Rogers retired in 1985, the end of a career in which he’d won 158 games and been an All-Star five times for the Montreal Expos. He had a petroleum engineering degree from the University of Tulsa and had plans to go into the oil industry. In the first nine months of his post-baseball life, the cost of a barrel of oil fell from $70 to $10. He went to work for the Players Association.

Fifteen years later, he began work with others on a pilot program that would assist players -- some active, others retired -- in career transition. A new iteration of that program formed in 2008, near the final days of Don Fehr’s leadership and the beginning of Michael Weiner’s, and the current multi-phased program took shape about six years ago.

The program is partnered with the Ayers Group, a division of Kelly Services. Approximately 100 players have taken the first step in that process, which is to meet with and undergo an evaluation by a career coach and design a path forward, usually continuing -- or restarting -- their education. (MLB funds the Continuing Education Program, which financially assists retired players as well, and many drafted high school players have college tuition written into their contracts.) The first phase is provided for free by the union and the Major League Baseball Alumni Association.

At the end of last week, Rogers was in Miami, where he distributed program information to the New York Mets and Miami Marlins. The week before, he said, three players, all recently retired, contacted him.

“It isn’t rocket science,” he said. “The truth of the matter is, it’s harder than hell to get to the major leagues. And it’s twice as harder than hell to stay there. So the entire focus is on getting there and staying there and ‘I’ll deal with the rest later.’ And ‘the rest’ hits just about everyone. And ‘the rest’ lasts longer. … It’s understandable. It’s not a negative. It’s the nature of the beast.”

So he goes clubhouse to clubhouse and leaves folders for players who believe the life-changing money is coming and the baseball will never end and possess neither the time nor the head space to consider the alternatives. And he monitors a program designed to explain what could be next, in English and Spanish, when the most pressing question in those clubhouses is -- and has to be -- what’s now. The rest, well, that’d be somebody else’s problem, until it isn’t.

‘I liked performing for the world’

Almost before that last hit fell, Ryan Kalish was on the phone with John Baker, a friend and former teammate and, today, a coordinator in the mental skills program for the Chicago Cubs. Though his body ached and his baseball was unaffiliated and he’d left his twenties behind, and though he’d had an idea this day was coming, Ryan knew he was in for a difficult ride.

“I really wanted it,” Ryan said. “I put myself through a lot of pain to try and play. This guy” -- he nodded to Lars -- “can attest to some of the surgeries that I had, the rehabs, the shoulder, the knees. The knees were the worst of it. Having neck surgeries, two of them. A lot of pain. And proving, fast, that I could play at the highest level. So it was hard for me to accept, wow, I’m really not going to get to prove what I think I could show everyone I could be. Everyone. As in the world, man.”

He laughed in spite of himself and continued, “I liked performing for the world. I liked to be on the stage. I wanted to do cool things. And eventually, I wanted to become an inspiration, too. I guess in some ways I am. But it would have been bigger on a bigger stage. I liked that. Inspiration just for a fight. Just to try. Like in whatever it is that you want to do just keep trying. Like, if you want something bad enough keep going. I don’t know. I really pushed the limits of how far I could go.

“Listen, I know people have had it worse. Ryan Westmoreland, that guy, I always think about him. I roomed with him during his brain surgeries and all that. So I know I don’t have it the worst. But I took it pretty far. I had it pretty bad in the injury department. So that was really hard to accept, that I’m not going to play anymore. I never got that chance. That was what was hard for me.”

Baker was raised in Northern California, played baseball at Cal, was drafted in the fourth round in 2002 by the Oakland A’s and played seven major league seasons as a catcher. He went home at 35.

“It’s like being thrown out of a helicopter into an ocean that is the real world,” Baker said. “Before that, you’re in perpetual Peter Pan-hood. You get to be a child. You live in a locker room. You’re around people who aren’t all that advanced from high school.”

Those are all good things. Good enough, anyway, that hardly anyone wants to leave, to go to a place where the game changes, where you make the schedule, where what’s next is a mystery and probably not all too comfortable.

“He called me from the dugout,” Baker said. “After the hit. He said he was done. The first thing, I wanted to make sure he was certain. Man, when he was healthy, he wasn’t just a good baseball player, he was one of the best baseball players in the world, a really special talent with a body that couldn’t withstand what a body could do.”

Ryan’s plan was to go to Europe for a while, watch Lars play in Germany, then bounce around, see the world and put some distance between himself and the previous 13 years. After that, he’d move back to New Jersey, start over there. He signed a one-year lease on an apartment in his hometown, broke that in two months, got in his car and headed west until he reached Gilbert, Arizona. John and Meghan Baker’s house. They shared a group hug at the front door and started the rebuild.

When the baseball goes, Baker said, three things go with it. First, the former player no longer has an obvious skill to master.

“Hitting is probably the most addictive thing in the world,” he said. “You get a hit and there’s a chemical release. You’re so happy. And then it’s the driving force to get up the next day.”

Second, he said, there is no more collaborative goal. No more team. No more scoreboard.

“When I first went home I was destroying my 3-year-old in tic-tac-toe,” he said. “That gets old.”

Then, he said, the ex-player has nowhere to put his mind.

“The amount of stress they endure when playing, 50,000 people screaming, a giant picture of your face, your stupid face, next to your crappy record,” he said. “We miss being under stress.”

So there was Ryan Kalish. Adrift. Scheduling cries. Refusing eye contact. Asking for help. For all Baker knew, Lars would be driving up any minute. He didn’t. He could’ve.

“Ryan was searching,” Baker said.

‘Whatever happened to that Lars guy?’

Lars Anderson sat this spring on a green knoll behind a backstop at Camelback Ranch outside Phoenix, where the Los Angeles Dodgers train. He’d kicked his shoes into the grass in front of him. He watched batting practice, the part of baseball he missed, and he watched a Dodgers coach flick ground balls with a Birdman Bat fungo.

From a ways back, he’d seen afternoons like this one coming. Maybe from the first time his name made the waiver wire here, or when he was released, or maybe from Japan or Australia or standing at first base as a Solingen Alligator of Germany’s Bundesliga. The breeze, the clack-clack-clack of BP, the music from the nearby ballpark, a case of new bats at his side, he said, those were enough. He was a salesman now, one of those buoyant souls who sets up a row of bats near the cage or outside the clubhouse and fights the earnest fight of the start-up.

He’d grown Birdman internationally. He’d assist in Birdman’s intentions to find a place among the corporate bat giants in the U.S. There was a long way to go and that was OK by Lars. He had the time. He had the interest. He had the game experience.

“I was not a guy who swung one bat,” he said. “I sampled all of them. I was very sanguine in my bat life, like a butterfly flying from branch to branch. So I got to know a lot about it just by accident.

“Sometimes you get a vibe about it. My dad, when he would take me to buy bats as a kid, he’d say, ‘Lars, when you pick it up it has to say ‘Yes’ in your hands.’ I kind of kept that with me throughout my career. The problem was a lot of bats said yes and then sometimes they would say yes for a month and then start to say no.”

The bat company, like their friendship, like their life paths, binds them. They went looking for an apartment recently, fairly certain Southern California would hold them for now. Ryan is gaining traction as a pilates instructor and part-time minor-league coach with the Dodgers. His brother, Jake, is a left-handed pitcher for the Kansas City Royals, pitching in Triple-A. Lars composes dance music and has written several first-person pieces for The Athletic. They still fret over their futures. They laugh about their pasts, the good parts and the not-so-good parts. They also have switched roles in recent weeks, Ryan now the settled one, fairly certain he’s on solid ground, Lars wondering what’s out there for him. Maybe a book about his travels in baseball. Maybe business school. And there’s still all those bats to sell. When I asked him who was most proud of the career he did have, he grinned and said his grandfather, who’d recently died.

“Any article about me, he’d print it out and you’d go to dinner with him and he’d hand the hostess that article,” Lars said. “I’m like, ‘She doesn’t care.’ He was just so stoked. He’d come to spring training, he’d come visit me during the season.

“But I was thinking, since he passed, all the people in the service industry are going to be like, ‘Whatever happened to that Lars guy? I haven’t got an update in a while.’ ”

He’s still working on that. So many of them are. What comes of those who made it, but didn’t quite make it? What happens when the last part is left undone? Where’s that sit in their heads? In their hearts? In their pockets?

“Once I knew there was a professional baseball, that you could do that for your job, that was what I wanted to do,” Lars said. “So, at 3 years old. I didn’t consciously choose my profession out of college or something. That’s what I’m doing now. But it was never even a choice. It was just, I’m doing it. Like it chose me. It wasn’t a 12-year career, it was a 31-year career. As soon as I could hit socks that my dad pitched me when he was folding them in the living room, that was it.”

Ryan grinned. Being an ex-ballplayer hasn’t been easy. Maybe it never will be. But it was inevitable. And it’s still better than the alternative.

“It always follows you, man,” he said.

“Yeah,” Lars said, “I don’t think that’ll ever go away, honestly.”

“It never goes anywhere,” Ryan said.

“I’m curious,” Lars said, “to see how that goes.”

More from Yahoo Sports: