The Future of Stadiums: How will America's sports venues be transformed by the pandemic?

The last time our nation lived through a cataclysm, it changed our sports forever. But 9/11 didn’t just change the way sports feel and sound, it also altered the places where our sports are played and watched. Stadiums added perimeters and several layers of security, the nationalism and militarism were dialed up, and the in-person experience was fundamentally different.

This coronavirus pandemic, likewise, will change our arenas and stadiums in ways both temporary and lasting. Because there are really two separate and distinct pieces to getting fans back into the venues: They have to be safe from the threat of a pandemic, and they have to feel safe. And it’s in the overlap between those two things that designers are seeking to find solutions to safeguard the stadiums of the future.

The short term

This pandemic will end. A vaccine will be made. Perhaps other pandemics will follow. Maybe we live in an age of pandemics now. Social distancing could come and go and come back again. But even if that is not the case, a new social awareness of the risks of large crowds will linger. That’s part of the equation in designing a stadium now, because it’s also in the calculus of buying a ticket to a game.

“Part of getting people to return is making sure that people feel safe and that all the things operators are doing are evident and communicated to their clientele,” says Bruce Miller, the managing director of Populous, a firm that has designed more than 1,300 sports venues, including 21 new or remodeled NFL stadiums. Fans won’t just want to hear what stadium operators are doing to keep the venue as clean as possible, they’ll want to see it too. The optics matter. And there will be some degree of theater involved in convincing the paying customer that their health is a priority.

Yet there’s a danger in overcommitting to the appearance of a safe environment. Gil Fried, chair of the sport management department at the University of New Haven, likens it to Israel’s airports. “If the average American is greeted by so much security, they think, ‘Hey, maybe this isn’t where I want to go,’” Fried says. “‘Maybe this isn’t safe.’”

“We don’t want our buildings to look like a hospital,” echoes Miller. “We still want people to feel comfortable, have a great time coming together around a sporting event.”

Managing a highly communicable disease in a large stadium is a complex process. To that end, Populous commissioned a study of touch-points, working out which surfaces in stadiums are touched the most by customers. “All of those touch-points can be changed and streamlined,” Miller says, “so that we minimize the touch-points that are required to attend an event.”

You can’t remove every surface that’s frequently touched. You can, however, clean them more often, and you can change the materials, switching to copper, which appears to be less hospitable to viruses than other metals.

Yet there’s only so much planning you can do for large crowds of sentient people, who tend to stand in clusters and move around a lot inside stadiums.

“We can draw on our computer screen a professional layout where everyone is social distanced,” says Nate Appleman, director of sports, recreation and entertainment at the HOK design firm, which designed the Atlanta Falcons’ Mercedes-Benz Stadium, among others. “And then the minute that you introduce humans into the equation it all goes completely haywire because there’s free will and choice. It’s really a challenging problem to solve. Without a vaccine, it’s only mitigation of risk; it’s not ‘safe.’”

Yet some teams are already drawing up elaborate plans for how to reopen, like the San Jose Sharks. Some states, like Texas, have already allowed the reopening of stadiums at 25 percent capacity but offer guidance no more specific than staying out of groups larger than 10, trying to keep 6 feet apart and wearing face masks. Other states, like Massachusetts, have said stadiums won’t reopen — at least not fully — until a vaccine is available. As in all other aspects of this pandemic, there is little national coordination.

Accelerating trends

The pandemic accelerated trends that were already in motion. The way we were designing and building stadiums was changing in significant ways.

“We’re in the middle of a time where I think we were already seeing fan expectations change for the live event before the pandemic actually occurred,” says Bill Johnson, the design principal at HOK, where he’s working on remodeling the Phoenix Suns’ arena right now, one of myriad arenas downsizing their capacity in favor of a more intimate feel. “A lot of these buildings were at a point where it was time to change them anyway. Now we’ve had to take a hard look at it. If we’re going to decrease capacity, how do we create that social experience when we’re trying to stay 6 feet away from each other?”

Some of those changes might actually be helpful in a pandemic scenario, like the growing prevalence of wearable tech in stadiums and arenas — which could be made to beep or vibrate when too many people occupy the same space, for instance. Stadium and arena apps that allow you to order food and drink from pickup spots seem tailor-made for this time as a sort of pedestrian curbside pickup.

On the other hand, trends like the reduction of suites in favor of more social spaces might have to be reconsidered.

But the big, universal tendency is for sports venues to reduce seating capacity. The last six Major League Baseball stadiums to open were all significantly smaller, capacity-wise, than their predecessors — all decreasing by a fifth or so.

The Texas Rangers went from 48,114 to 40,300.

The Miami Marlins from 47,662 — which was already capped in its gargantuan facility — to 36,742.

The Atlanta Braves downsized from 49,586 to 41,084.

The Minnesota Twins from 46,584 to 38,544.

Even the New York teams cut down significantly when they opened new stadiums opposite their old ones in 2009. The Mets went from 57,333 to 41,992; the Yankees from 56,936 to 47,309.

The Tampa Bay Rays’ Tropicana Field can hold 42,735 but tarps cover almost half of those seats to reduce them to just 25,000, the lowest in the league by 10,000.

Helpfully, while capacities are going down, the size of stadiums and arenas isn’t necessarily following suit. Because the space saved on those seats is often used on upgraded amenities, increasing food options and other forms of entertainment on the grounds. And many venues now have more flexibility than ever in moving seats around.

These facilities are, in other words, more suited to a pandemic than ever before. It’s hardly inconceivable that seats will be spaced out further and that the room this opens up will be used to ramp up the experience further with things like TV monitors to watch replays or mini-fridges, saving you the trip to the beer concourse.

In the NBA, the emphasis has been on getting the quality of the consumer experience right, even if it’s at the expense of quantity. In those arenas, some three-quarters of ticket revenue comes from the first 20 rows or so, according to the Sports Business Journal.

The younger generations of fans growing into enough disposable income to afford those premium seats don’t actually like to be tethered to them. “They like to get up and walk around and see the game from different perspectives,” Johnson says. “They like to capture and be in the moment when sports are happening and be able to broadcast that out.”

The trick is to create enough room for those roving fans not to bunch up, yet to feel like they’re having a social experience.

Spreading out

Like 9/11, the coronavirus will add crush points to sports venues as new layers of security are added on. Except this time around, the congestion is problematic in and of itself. Because long lines for temperature scans, for instance, have to be spaced out. As do potential queues for security, ticket-scanning, concessions and bathrooms. Footprints of stadiums may have to increase.

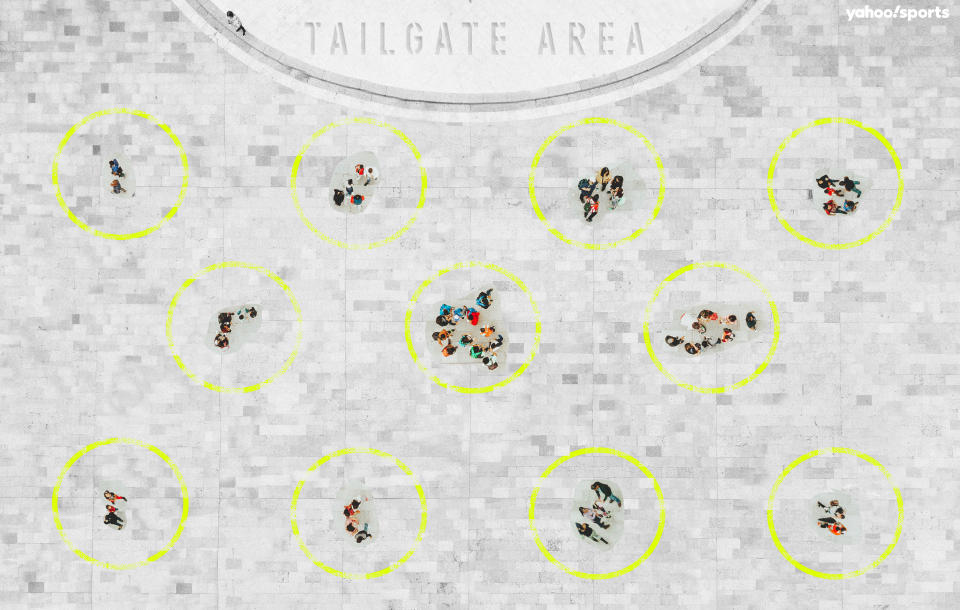

But here, too, an existing development might help. Fewer people are driving to stadiums and parking there. Between rideshares and improved public transportation alternatives— when the latter become safe again— parking lots can be reduced. Some form of tailgating will likely survive as a means of gathering with friends before the doors open, but it may not necessarily take place in parking lots anymore, but rather in areas designated for just that purpose.

The evolution of virtual reality may also reduce the physical crush of people in stadiums. VR has grown so sophisticated that it can place fans inside the stadium from their couch and has excited stadium designers for some time.

Only a fraction of most major teams’ fans actually regularly go to games in person, for reasons that are usually financial or geographical. Trying to create an experience for those fans that makes them feel like they’re there, in person, is the next frontier for the sports industry — and potentially fertile ground for new revenue. It also softens the blow of not being able to be there personally while still allowing for the existing business model to survive.

“You could physically sell one of those 60,000 seats,” says Mark Williams, business development director and sports principal of HKS, which designs sports venues around the world, including SoFi Stadium, the new NFL stadium under construction in Los Angeles. “And you may have another 100 people paying to have access to the offerings in that same seat that somebody is actually sitting in. They would see that perspective, look around, see the event. That’s limitless.”

In other words, if our new normal forces us to build 20,000-seat stadiums instead of 80,000 ones, putting people in the stadiums virtually can perhaps salvage the lost revenue and save the product we’ve grown accustomed to.

The money issue

The revenue model in big-time sports was already changing from maximizing capacity to improving the experience and extracting more dollars out of fewer fans.

Because sports broadcasts have become so sophisticated and accessible — pay enough and you can see any pro team and just about any Division I college team from anywhere in the world — it takes more to get fans to shell out for tickets, sit in traffic, park and push through the throngs of people to watch a game in person.

“That’s been the battle for the last 20 years,” Appleman says. “How do we create an experience beyond just having the players on the field or court, that lures people out to come to the venues?”

Should caps on attendance be imposed on teams in existing facilities, financing issues will follow. When fewer people come through the door, you have to make up that revenue someplace else in order to service whatever debt you took on to build the place. Stadiums are designed to be full — as are the neighborhood developments that tend to follow. And the plan to pay for those stadiums, and whatever surrounds them, needs seats to be filled too. To avoid defaulting on payments, making the most money from the people that do come, as well as monetizing tech, will become ever more important.

But, as Fried points out, that will only worsen the gentrification in our sports stadiums. In a nation where almost half the population reportedly can’t cope with a $400 emergency, the cost of taking a family to a professional game is often prohibitive.

“Will this provide a different dynamic for facilities moving forward? I would think so,” Fried says. “I think we already have the haves and the have-nots in sports. A lot of the Average Joes have been priced out. With the quality of the broadcast, going is just too expensive. This pandemic is just moving that along.”

Even if the pool of people who can afford to go gets even smaller — and the onset of a deep recession doesn’t help any — the stadiums will eventually reopen and people will return. Stadiums and arenas form part of the social nucleus of our cities, going back to the Roman Coliseum, and leave an outsized footprint on our imagination.

It’s just that when they do, those buildings will have changed as much as the times have. And soon, they’ll change further still.

Leander Schaerlaeckens is a Yahoo Sports soccer columnist and a sports communication lecturer at Marist College. Follow him on Twitter @LeanderAlphabet.

More from Yahoo Sports: