The ballad of a contact hitter: How Mets All-Star Jeff McNeil became a hitting machine

ARROYO GRANDE, Calif. — In a roadside joint a long way from where the New York Mets tried again to herd their season toward something presentable, their leadoff hitter, Jeff McNeil, appeared simultaneously on three cellphone screens. He was in a batter’s box in Philadelphia that afternoon, set low into his back leg, the bat laid near his left ear.

Their boy. It could only be their boy.

“Home run,” his mom said.

“Home run?” his dad responded. “Home run.”

“Yep,” his brother said. “Shoulda had one yesterday.”

“Dead center, looked to me,” his dad said.

“No, it was left-center,” his brother said.

“Looked like something offspeed,” his dad said.

“I mean, he was an inch away yesterday,” his brother said.

“Curveball,” his dad said.

“You’re welcome,” his brother said, smiling. “You’re welcome. I’ve thrown him a lot of hangers, so …”

“Kinda surreal,” his dad said.

“It’s pretty cool,” his mom said.

Jeff McNeil is from down the road, in the town of Nipomo, which is famous for, among other things, Jocko’s, a rustic steakhouse where Jeff McNeil waits hours for a table like everybody else. Nipomo also is home to the golf club — Monarch Dunes — that this winter counted among its cart boys the future National League All-Star for the Mets. It was an unpaid position, as McNeil took in trade lunch and a few rounds of golf. He was, by accounts, mildly disappointed not to win the Christmas party raffle. It was a nice TV.

The baseball in Nipomo looks like the baseball anywhere, hot and dusty and earnest and ultimately a way to kill time before adulthood, though there was that one season when the high school team had two future professional ballplayers, both by the name of McNeil, one a pitcher with a heavy fastball and the other a shortstop with the most dog-gone knack for putting a bat on a ball around here since Robin Ventura.

Today that McNeil — Jeff — leads Major League Baseball in batting, is a .340 hitter over 500 major league at-bats (only Wade Boggs and Joe DiMaggio had more hits than McNeil’s 170 in their first 500 at-bats) and is wholly content with the basic swing mechanics that were good enough at a place called Batty’s, in a backyard Wiffle Ball duel against his brother, on summer ball fields and at Long Beach State and in Cape Cod and wherever big ol’ smug pitchers tried to throw fastballs past narrow-shouldered and fungo-slim guys who wouldn’t have it.

He also has hit 10 home runs across those 500 at-bats, which is about right for a 6-foot-1, 190-pound guy in plenty of eras other than this one. But Jeff McNeil has always hit. Always. He has always deplored strikeouts, which, again, is a standard from another time and place. He still remembers the umpire who rung him up in a Little League game when he was 12, because it was his first strikeout in four years. And also because the umpire was Jim McCann, who is Chicago White Sox catcher James McCann’s father.

“In Little League, I could count on one hand the amount of times I struck out in a year,” Jeff said this week. “It was always about putting the ball in play, getting on base. I guess I haven’t really changed my game a lot.”

He laughed a little, the way you do when admitting that what was an experiment became a habit, then an obsession, then a life’s course.

Steve McNeil and his son were regulars at Batty’s Batting Cage, where a token would get you 20 cuts. The guy behind the counter would give the McNeils a deal on 25 tokens. Steve would stack the tokens on the metal box with the switches and lights, close the chain-link door, sit on the bench behind the cage, open his book and see what the latest James Patterson story was all about.

Jeff McNeil was hardly any bigger than the gray aluminum bat in his hands. The helmet on his head wobbled when the wind gusted. He wore baseball pants. He always wore baseball pants. He was 4.

A year before, Steve had started Jeff in the softball cage, which a single token determined was maddeningly easy. Steve had shrugged and guided Jeff to the cage where the machine looped 35-mph fastballs. The first one had hit Jeff in the helmet. He’d inched away from the plate. The second one he’d struck square on the bat barrel. On contact, his little arms had recoiled and the bat followed, circling his body like a tetherball until it clunked into the back of his helmet. Steve had looked up, then down again, to see what the latest David Baldacci story was all about. Jeff had already raised his bat for the next one.

Jeff swung a bat left-handed, just as he did a plastic golf club, and his parents — Steve and Rebecca — figured he was left-handed, except he came to do everything else right-handed, including throwing a baseball. Any confusion was lost in the routine of those 25 tokens, of those 500 pitches, of those 500 swings, of those father-son afternoons near the beach in Santa Barbara. And there were 500 swings. Always. If the machine was going to shoot 500 baseballs, then Jeff was not going to waste its time or his by watching a single one fly by. Or bounce by. Or skip by.

No, Jeff McNeil came to hit.

On a recent weekday afternoon, minutes before the evening East Coast baseball games started, Steve, Rebecca and Ryan McNeil met in a local joint here known for its beer, burgers and big televisions. Rebecca had a Chardonnay. According to the live streams on each of their cellphones, the Mets were in Philadelphia. Jeff McNeil was batting leadoff, playing right field.

By the end of the coming weekend, Jeff would be batting .349, best in the major leagues. He would be an All-Star. At 27, and 136 games into a big-league career not yet a full year along, his is the story of the late bloomer from California’s Central Coast who didn’t play high school baseball until his senior year, who needed a nudge to play college ball, who was drafted 356th overall in 2013, who spent five full seasons in the minor leagues, who then hit .337 in 11 months against the best pitchers in the world. The story is told as if he walked in from a corn field, when in reality he didn’t come out of nowhere, but from a family that encouraged him — and his younger brother, Ryan, and their older sister, Emily — to join and play what they wanted, when they wanted, and how they wanted. The only rule was once they were in, they were in. McNeils didn’t quit.

Rather than cling to a single sport, Jeff played golf. He played soccer. He played basketball. He dunked tokens into pitching machines, played backyard Wiffle Ball against his brother to exhaustion and played all the baseball that would have him around his other pursuits, then was overlooked by many of the standard methods of evaluation and projection, and still grew up to be the guy on mom and dad’s phones when the chicken fingers and giant pretzel arrived.

“Nobody’s ever known who Jeff McNeil was,” his brother said. “We do.”

“He’s finally getting credit for everything he’s done,” his mom said.

“Everything he’s done his whole life is coming to a point,” his brother said, then added, “Jocko’s is bigger than Jeff McNeil. I promise you that. Ask anybody in here if they know Jeff McNeil and ask them if they know Jocko’s.”

“When Jeff McNeil is bigger than Jocko’s, then you’ll know he really made it,” his mom said.

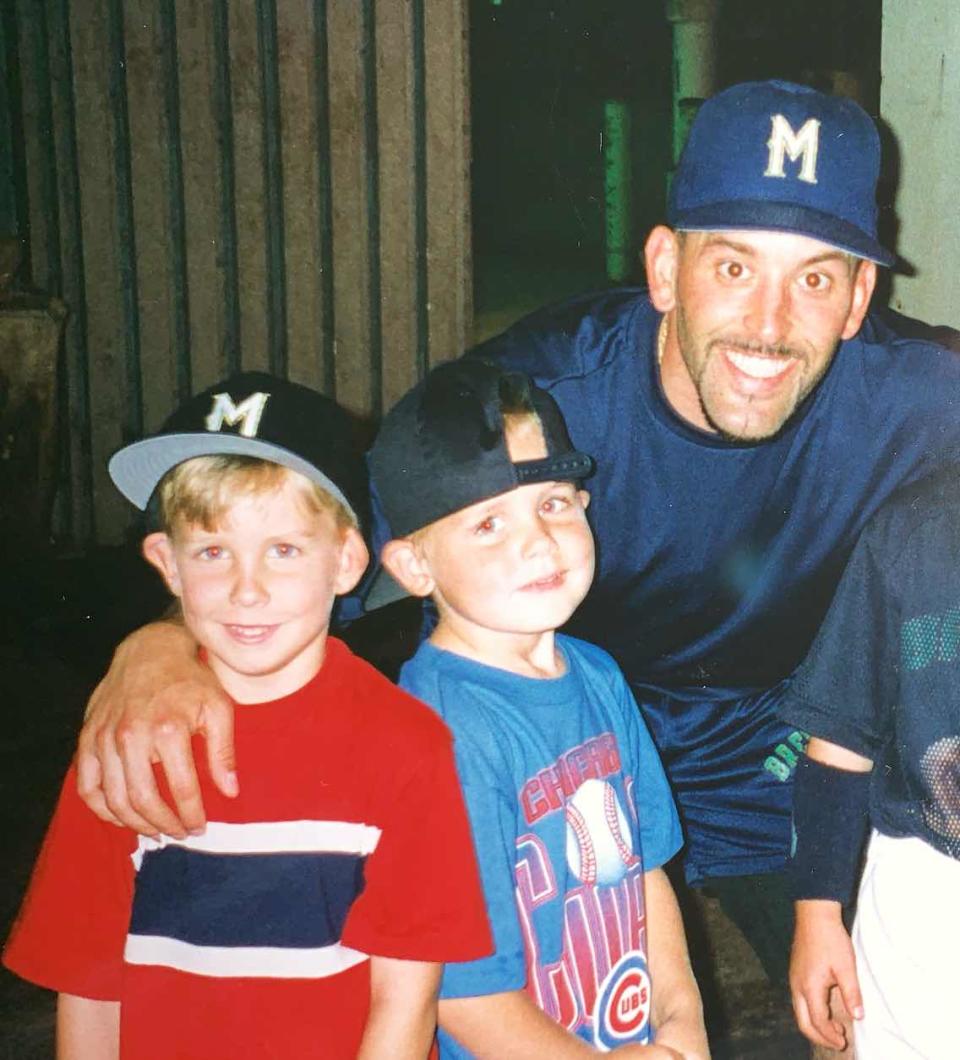

Steve is a firefighter. That thing about McNeils not quitting? He became a firefighter at 40. Rebecca is a bookkeeper. Ryan is a pitcher. Or was a pitcher. Or will be a pitcher. He was a third-round draft pick of the Chicago Cubs in 2012. He had a big fastball and, for a high schooler, uncommon command. He also had Tommy John and hip surgeries in the years after the draft, was slow to recover from both, and last July 4 was released. He’d reached Double-A. Every couple days, he plucks baseballs from a bucket and fires them into a net, seeking to heal his body and return to the game.

Nipomo is farm country, a few exits along U.S. Route 101 about 70 miles north of Santa Barbara. Steve’s truck has 250,000 miles on it. Rebecca’s Dodge Charger has 394,000 miles. That’s a lot of parenting.

Steve has a brush cut, blue eyes and the chest and arms of a guy who hauls hoses for a living. Rebecca laughs with ease and is the first to introduce herself. Steve played Little League baseball until he was 13. She’d been a dancer. They began their family in Santa Barbara, where Steve owned and operated several small businesses, including restaurants and a men’s clothing shop, where, among other services, he’d take in James McCann’s oversized chest protectors. When the boys became consumed by sports, and baseball in particular, Steve and Rebecca had gone along, doing the driving, replacing the backyard fence with a gate so they could fetch the home run balls, organizing the fundraisers, slicing the oranges.

They are hopelessly proud. They finish each other’s sentences and remain freshly amused by family stories that often end happily (and with something glued back together) and are not the least bit surprised, frankly, that the hyper-competitive kid who had to be playing something — and winning at it — is still at it. And if you were to ask, say, who Jeff’s favorite player was growing up, that would be about the first moment of silence across the table.

“Jeff was probably Jeff’s favorite player, if I had to guess,” Ryan said.

“Yes. Yeah. I absolutely agree,” Rebecca said.

“‘Cause he knows he’s good,” Ryan said.

“Because he could always do it,” Steve said.

“Yeah, he’s an interesting kid. He’s a middle child, if that helps,” Rebecca said.

Steve grinned and held up his hand, because if you wanted to know what drives Jeff McNeil, what has always driven Jeff McNeil, and what will drive him well past a couple New York summers, well, he had a story for that. And Rebecca and Ryan smiled, too, probably because they knew what was coming.

“He was, I want to say 5 years old. Maybe 6. Kindergarten. And I took him to the little golf course. First hole, tees up his ball. Stands back. He’s got his driver out. It’s 90 yards, but he’s got his driver, right? And he’s taking practice swings. Well, he used to take his practice swing, he’d get real close to his ball. I say, ‘Dude, back up a little.’ He doesn’t. Takes two more practice swings. Well, he hits the ball. Goes 45 degrees, breaks the light on the outside of some guy’s condo. So I’m sitting here trying not to laugh. But I’m looking at him, going, ‘What happens? Fight or flight? Does he run? Does he cry? What is he going to do?’ He looks up and he says, ‘Does that count?’ Didn’t care that he broke a light. He needs to know if he’s hitting three off the tee or does he still have his one. All about the scorecard,” Steve said.

So, perhaps, if you have to know where the next generation of contact hitters is coming from, assuming there’ll be any left by then, it could be from a quiet place like here, from lovely people like these, from a spot in the draft like that, from a soul that won’t believe it can’t.

“Double,” Rebecca said.

“Double? Double,” Steve said.

Another hit. Imagine that. Another day doing what he always did.

“Well, it’s definitely kind of unbelievable,” Jeff said. “But I knew it was possible.”

Their boy. It could only be their boy.

More from Yahoo Sports: