How 'The Tackle' sparked a friendship between Kevin Dyson and Mike Jones

Not long after he fell a yard shy of Super Bowl glory, Kevin Dyson’s disappointment began to evolve into an unhealthy obsession.

All the Tennessee Titans receiver thought about was that he had let down his teammates, that he could have done more on the game’s decisive play to avoid being tackled an arm’s length short of the goal line.

Dyson believed he was on the verge of scoring a last-gasp, game-tying touchdown when he snagged a pass across the middle in the dying seconds of Super Bowl XXXIV. St. Louis Rams linebacker Mike Jones instead made a game-saving tackle from a difficult angle, securing a championship for his team and sending Dyson spiraling.

For weeks, Dyson picked at his food during meals, sequestered himself from friends and family, and restlessly tossed and turned in his bed at night. He even made an emergency visit to his dentist when his stress triggered an outbreak of lesions in his mouth.

[Ditch the pen and paper on football’s biggest day. Go digital with Squares Pick’em!]

“I had like 20-something canker sores and they were so painful that tears were coming to my eyes,” Dyson said. “The dentist felt so bad for me. He told people afterward he had never seen so many canker sores in somebody’s mouth at one time before.”

Nineteen years to the day after his Super Bowl setback, Dyson no longer torments himself for not reaching the end zone. He doesn’t dread the annual media requests he receives to relive his biggest football disappointment anymore, nor does he cringe anymore when he sees replays of himself futilely stretching for the goal line.

As Atlanta prepares to host its first Super Bowl since that Rams-Titans masterpiece in 2000, Dyson is at peace with his enduring fame for being on the wrong end of one of the NFL’s most iconic plays. It’s a shift in mindset he attributes in part to the influence of an unlikely friend – the man who tackled him.

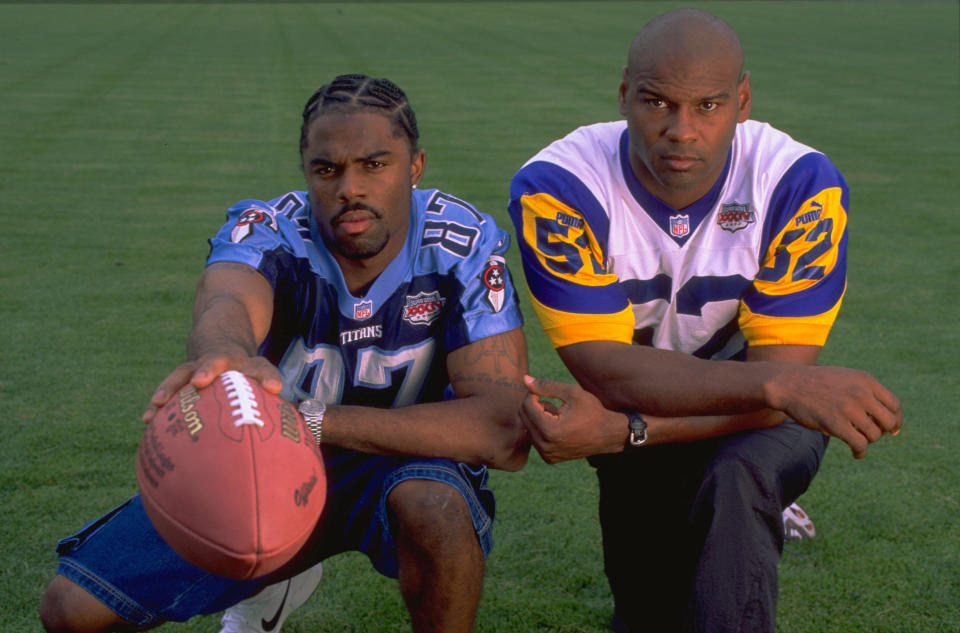

Dyson first formally met Jones before an August 2000 preseason game between the Rams and Titans in Nashville. ESPN invited both men to watch the dramatic play together on camera and to share their perspectives of it with one another.

Reliving the intricacies of the play with Jones proved cathartic for Dyson, easing his stress level and enabling him to heal. The Rams linebacker modestly downplayed his own accomplishment, describing the sequence as just “a good football play” in which both he and Dyson did what they were taught to do.

“He wasn’t pounding his chest like he made the greatest play in history,” Dyson said. “He was more like, ‘Shoot, I just made a play, but it could have gone either way.’

“He ended up giving me a whole new outlook. I was able to be at peace with what happened and release it instead of holding onto it. Up until then, it kind of hovered over me.”

Subsequent conversations with Jones further reinforced that Dyson had no reason to feel shame or remorse. The two ex-players typically make public appearances together every couple years and keep up with each another via sporadic text messages.

What has further strengthened their bond is that both have pursued similar careers since retiring from the NFL. Both are helping kids, Jones as a football coach in St. Louis and Dyson as a coach and assistant principal at a high school in the Nashville suburbs.

“It’s pretty cool that all this has led to a friendship,” Jones said. “Every time I see him or talk to him, he’s always in good spirits. He knows that play didn’t make him as a player. He had a whole lot more good than bad. He just came up short on one play on a big stage.”

While Dyson and Jones work in similar realms now, their paths to professional football were entirely different.

One was a first-round pick whose NFL career lasted only six years because of a rash of injuries that robbed him of his physical gifts. The other was a former undrafted free agent who had to defy the odds and learn a new position to carve out a 12-year NFL career.

The Titans made Dyson the first receiver taken in the 1998 NFL draft, five spots ahead of future Hall of Fame inductee Randy Moss. They liked what the sure-handed University of Utah standout flashed against fellow NFL prospects at the Senior Bowl that year and they viewed him as a safer choice than the talented but volatile Moss.

By that time, Jones was an established veteran seven years removed from not hearing his name called during the 1991 NFL draft. The record-setting University of Missouri running back gained a foothold in the NFL only because the Raiders believed he had the ability to transition to linebacker, a position he hadn’t played since high school.

There was little reason to believe the careers of Dyson and Jones would converge during Super Bowl XXXIV before the 1999 NFL season began. Neither the Titans nor Rams were projected to contend for division titles, let alone dethrone the Broncos as Super Bowl champions.

A miracle backup QB, and a miracle play

The truly unfathomable long shot was a Rams team that at the time had the NFL’s worst record in the 1990s and was coming off a 4-12 season. ESPN’s preseason power rankings pegged the Rams 25th out of 31 teams even though they made several key moves aimed at energizing a lackluster offense, signing quarterback Trent Green and guard Adam Timmerman, trading for running back Marshall Faulk and drafting receiver Torry Holt.

There was optimism in St. Louis as a result of the new additions until Green suffered a season-ending knee injury during the preseason. That meant Rams coach Dick Vermeil had to entrust his starting quarterback job to a former Arena League player just a few years removed from stocking shelves at the grocery store.

“When Coach Vermeil said we’re going to win with Kurt Warner, you could hear a pin drop in the meeting room,” Jones said with a chuckle. “We didn’t know what we had. In the back of our heads, we were thinking, ‘Oh man, we’re in trouble.’ ”

Turns out Warner did OK as the Rams’ starter. More than OK, in fact.

All he did was pilot a prolific offense that earned the nickname the Greatest Show on Turf. Aided by the presence of Faulk and a deep, talented receiving corps, Warner threw for 4,353 yards and 41 touchdown passes, leading the Rams to a 13-3 regular-season record and the franchise’s second Super Bowl appearance.

Tennessee’s run to the AFC title was also unforeseen by NFL prognosticators. Not only were the Titans coming off back-to-back-to-back 8-8 seasons under Jeff Fisher, the biggest changes they made in the offseason were a new team name, new uniforms and a new stadium.

Behind the rushing of Eddie George, the strong arm of Steve McNair and the emergence of rookie pass rush specialist Jevon Kearse, Tennessee won over its new market and rid itself of the negative Oilers image. The Titans went 13-3 in the regular season and then won three playoff games, the first in truly remarkable fashion.

When Tennessee surrendered a go-ahead field goal at Buffalo with 16 seconds left in a wild-card game, the Titans’ lone silver lining was that they had a trick kickoff return play ready for such a scenario. The only problem was the two primary return men who had practiced “Homerun Throwback” both suffered injuries earlier in the game.

Forced to search for someone with a background returning kicks in high school and college, Fisher turned to Dyson.

“They were calling my name, and I was all discombobulated,” Dyson said. “I had never been on the field when we practiced the play. I’d never paid much attention to it. You see it run. You get the gist of it. But like most guys who weren’t part of it, I was one foot out the door, trying to get home or to the plane, thinking, ‘We’re never going to run this.’ ”

Fortunately for Dyson, his role in what’s now known as the Music City Miracle wasn’t all that complicated. When tight end Frank Wycheck threw a lateral pass across the field to him, all he had to do was sprint down the sideline untouched for a 75-yard, game-winning touchdown that sparked the Titans’ Super Bowl run.

Life after the catch, tackle

The Super Bowl matchup between the favored Rams and underdog Titans appealed to both teams for different reasons.

The Titans were quietly confident because they had edged the Rams 24-21 in Nashville earlier that season. The Rams were eager for a chance to avenge one of their only two regular-season losses in which their starters participated.

“If there was any team we wanted to play, it was Tennessee,” Jones said.

Warner’s 73-yard touchdown strike to Isaac Bruce gave St. Louis a 23-16 lead with less than two minutes to go in the fourth quarter, but the Rams weren’t in as strong a position as it initially seemed. Their defense was exhausted, having been on the field for most of the second half.

McNair took advantage, spearheading an efficient two-minute drill with his strong arm and elusive feet. The Titans took their final timeout with the ball on the Rams’ 10-yard line and enough time to run one more play.

Fisher called a play designed to beat the zone defense he expected the Rams to deploy. All McNair had to do was watch what Jones did in pass coverage from his right-side linebacker spot and make the appropriate read.

If Jones let Wycheck run free on a corner route, McNair would know his Pro Bowl tight end had 1-on-1 coverage against a smaller defensive back. If Jones turned his back and ran with Wycheck, McNair would have Dyson free on a shallow route across the middle with room to run after the catch.

The Titans got the look they were expecting from the Rams, but Jones defended the play perfectly. His eyes remained trained on Dyson even as he ran with Wycheck, enabling him to leave the tight end as soon as he saw the receiver angle his route toward the vacant middle of the field.

“I still was able to make the catch and turn up field, but his determination and will allowed him to get his arms around me so I couldn’t extend,” Dyson said. “That was the difference in that play. Even if he gets a hold of me with just his right arm, I’d still have been able to run through the tackle or extend and get those last 3 feet.”

As Dyson reached for the end zone in vain, Jones glanced at the referee spotting the ball short of the goal line before raising his arms in victory. It was all the celebrating he had energy to do after that gut-churning finish to an already draining second half.

Hailed as the Rams’ unlikely hero, the unheralded linebacker who bailed out the Greatest Show on Turf, Jones made the rounds on the New York talk show circuit after the Super Bowl before signing autographs and posing for pictures when he returned home. All the attention was uncomfortable for the veteran linebacker because he didn’t think it was warranted.

“It wasn’t a one-handed interception,” Jones said. “I didn’t beat an offensive tackle to get a sack or force a fumble. It was something I did every single day. I made sure I was in good position to make a tackle. It just happened that the tackle I made was on the last play of the Super Bowl.”

Jones played three more seasons in the NFL before trading his helmet and cleats for a whistle and clipboard. He won a state title in his first season as head coach at Hazelwood East High School in St. Louis in 2008 and just finished his first season coaching St. Louis University High School.

While Jones’ players and their parents will occasionally ask about his Super Bowl-clinching tackle, the former Rams linebacker almost never brings it up himself. He has no photos or memorabilia from the Super Bowl in his office nor his house.

“I wear my ring around more than I used to,” Jones said. “That’s probably the only thing I do.”

Dyson thought he, too, would pursue coaching after injuries cut short his playing career, but opportunities were more scarce than he expected. NFL and college coaches offered only internships and grad assistant positions, preferring that he prove he wasn’t one of those former athletes who viewed coaching as a cushy gig and wouldn’t put the hours in to be successful.

Undaunted, Dyson transitioned to the field of education and embarked on a new challenge. He now has two master’s degrees and a doctorate in education, leadership and professional practice, massive achievements for a man who once was content doing the bare minimum in high school and college to stay eligible to play sports.

“Sports were my passion,” Dyson said. “There was nothing in my life that suggested I was going to have two degrees and a doctorate. If you’d told me when I was 15 years old that I was going to be Dr. So-and-So, I’d have laughed in your face. I say that to explain why I am so proud of that accomplishment. I did not think I was capable of accomplishing that.”

Though Dyson wants to be defined by more than football, he also enjoys answering questions about his role in a couple of iconic NFL plays. Even the one that left him crying in pain in a dentist’s chair 19 years ago.

“I don’t bring it up myself but I don’t run from it,” Dyson said. “If you get to the biggest stage and you come up short, it’s a tough pill to swallow, but at the same time, to still be talked about 19 years later is something I appreciate. I was a role player, not a Hall of Famer, so to still have something that keeps you relevant, I don’t take that for granted.”

More from Yahoo Sports:

• Report: Trump to make a play on Super Bowl Sunday

• Lonzo not interested in playing for Pelicans

• ‘Madden’ predicts winner of Super Bowl LIII

• Wetzel: Comics try, mostly fail, to make Bill Belichick laugh