'Scranton v Park Avenue' is Biden's best campaign issue – not the supreme court

With the death of the US supreme court justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg last Friday, the stakes of November’s election are more obvious than ever. If Trump retains control of the presidency, most likely through a win in the electoral college but loss in the popular vote, that will cement minority Republican rule for a generation. Abortion rights, healthcare legislation, labor protections and voting rights will all be directly impacted.

Democratic partisans are acutely aware of this fact. ActBlue, the party’s most important fundraiser, raised more than $100m from 1.5 million individuals since Ginsburg’s passing. For some, like the New Yorker’s Jeffrey Toobin, Ginsburg’s death means that Democrats need to ratchet up their rhetoric about the courts and foreground their plans for significant institutional reform. If Democrats can take the Senate, Toobin suggests, then the filibuster must be abolished, Washington DC and Puerto Rico granted statehood, the number of lower-court federal judges expanded, and the supreme court be packed with three more judges. On the latter point, at least, the Senate minority leader, Chuck Schumer, agrees, saying that “everything is on the table”.

Related: The US supreme court has become a threat to democracy. Here's how we fix it | Sabeel Rahman

Many of the same commentators and strategists getting on board with plans like court-packing think that Biden should be trying to appeal to moderate Republican suburban voters. But there is an unacknowledged tension here: Ginsburg’s passing will likely limit defections from the small cadre of Republicans who find Trump distasteful enough to contemplate a Biden vote. Many of these voters may think a conservative court is worth the embarrassment of being associated with another Trump term.

The problem with treating the election as a referendum on the supreme court is that, as Anne Applebaum recently argued, it “organizes the electorate along two fronts of a culture war, and forces people to make stark ideological choices. Instead of focusing voters on the president’s failure to control Covid-19 or the consequent economic collapse, the culture war makes voters think only of their deepest tribal identities.” But whether Applebaum wants it to be the case or not, the courts will be the forefront of the minds of many regular voters. Recent events, then, should call into question the entire Biden premise of building a campaign around current or former Republican voters in affluent suburbs.

Another strategy – instead of chasing suburban voters uncomfortable with Trump’s conduct – is to offer bread-and-butter issues to lower propensity young and working-class voters, who Bernie Sanders had tried to mobilize in his primary run to varying levels of success. (Perhaps easier accomplished in a general election rather than in closed party primaries.) While the culture war might divide much of the existing electorate, this new electorate can be potentially reached through appeals for widely popular progressive policies such as universal healthcare and a federal jobs program. In a time where millions of Americans are living paycheck to paycheck – and many are experiencing unemployment and an uncertain future – offering more security and support is a message that can win an election.

Though they obviously overlap, the 64% of Americans who think the rich should pay more in taxes to support public programs are a firmer basis to build a political coalition than the quarter of Americans who identify as “liberal”, or, for that matter, the probably tiny number of former Trump voters who can be won over to Biden by outrage at the president’s behavior. Rather than talking about “packing the courts”, Biden would be wise to appear credible on this bread-and-butter agenda and then use his mandate to “do whatever it takes” in the way of structural reform to accomplish it.

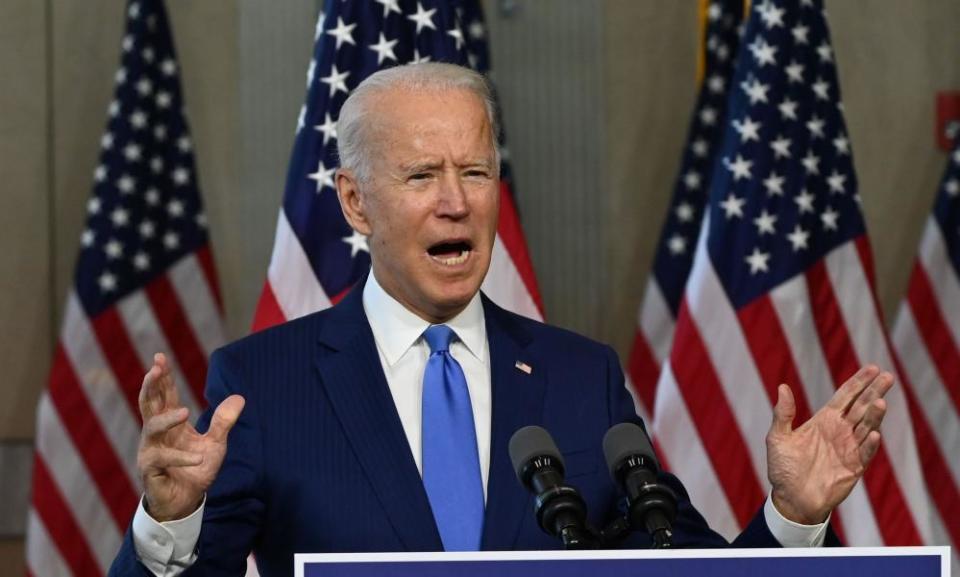

The former vice-president has been making some populist noises lately, such as when he recently framed the election as a choice between the interests of “Scranton” and “Park Avenue”. (This sparked the ire of the liberal MSNBC crowd, who, in an incredible encapsulation of their own irrelevance and privilege, attacked Biden’s framing for being divisive and Trump-like.) But he’s not always consistent in this messaging.

There is still time for Biden to embrace a populist message more resolutely, and speak to the millions of Americans looking for a strong, progressive leader who can help them weather this economic storm – much like FDR did during the Great Depression. The question isn’t whether Biden should pursue this path, but whether he will – and whether people should believe him if he finally does.

Bhaskar Sunkara is the founding editor of Jacobin magazine and a Guardian US columnist. He is the author of The Socialist Manifesto: The Case for Radical Politics in an Era of Extreme Inequality