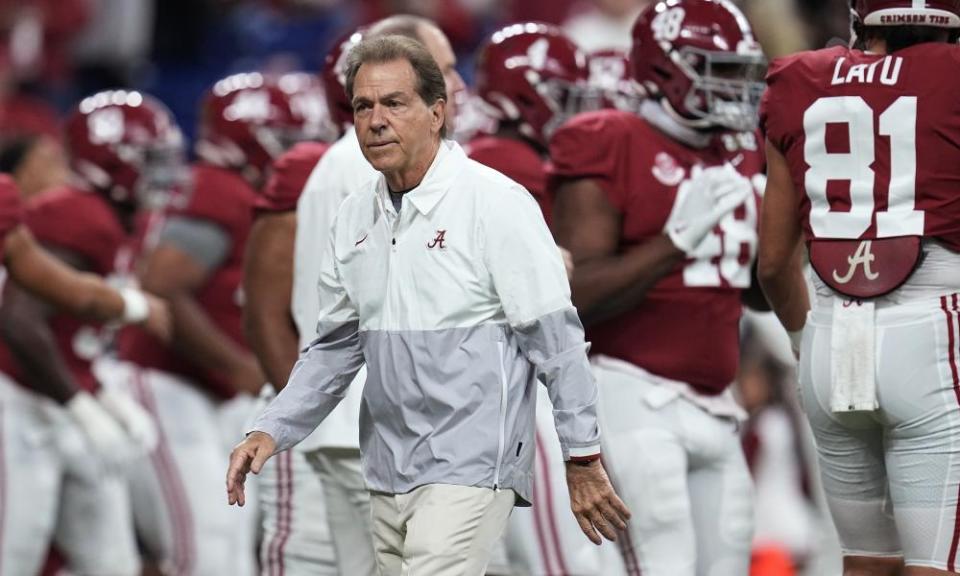

‘Saban is a narcissist’: why two star college football coaches are at war

The biggest feud in US sports right now is not between two rival teams or young-and-hungry athletes, but between a pair of head coaches who qualify for AARP membership. If you guessed that we’re about to discuss college football, you are correct. Last week, Alabama’s Nick Saban and Texas A&M’s Jimbo Fisher traded insults, suggesting that nobody is quite sure how the new era of college football, in which players can now make money from sponsorship deals, is supposed to operate.

Saban shot first. After Texas A&M were named as having this year’s No 1 recruiting class, Saban went on the offensive. “We were second in recruiting last year,” he said, “A&M was first. A&M bought every player on their team. Made a deal for name, image and likeness [NIL]. We didn’t buy one player.”

To be more specific, Saban was accusing Fisher of luring players by promising them NIL perks. Before last year’s rule change, the NCAA didn’t allow players to capitalize on their fame through endorsements or paid public appearances. It’s still uncertain how these changes will be monitored by the NCAA, but Saban seemed convinced that the Aggies head coach was doing something unethical while amplifying rumors that boosters connected to the program had directly or indirectly promised upwards of $30m to this year’s recruits.

Related: Race, money and exploitation: why college sport is still the ‘new plantation’

During a very lengthy public response, Fisher first defended his players (and, of course, himself). “We never bought anybody,” the coach said last Thursday. “No rules are broken. Nothing was done wrong. It’s a shame that you’ve got to sit here and defend 17-year-old kids and families and Texas A&M.”

All of that was well and good. Fisher, who happened to be Saban’s offensive coordinator at LSU for a spell, deserved the right to respond to serious accusations. However, where he went next took this from a petty squabble to all out war.

After labeling Saban a “narcissist,” Fisher painted his former boss as a near Satanic force in the sport. “We build him up to be the czar of football. Go dig into his past, or anybody’s that’s ever coached with him. You can find out anything you want to find out, what he does and how he does it. It’s despicable,” said Fisher.

Fisher has one thing on his side: Saban is uniquely hated among college football fans, in a similar way to New England Patriots head coach Bill Belichick’s standing with NFL fans. The antipathy directed at both men is due to a combination of their ridiculous levels of success, blunt personalities and the impression that their teams benefit from borderline illegal practices. Fisher is almost assuredly correct when he says that others around football feel the same way, especially opponents who have watched Saban win seven national championships, six with Alabama.

However, Fisher both responded too harshly and left himself vulnerable to counterattacks. After Fisher left Florida State University, plenty of stories emerged that depicted him establishing a culture of entitlement, particularly with star quarterback Jameis Winston. While fans may enjoy him tearing into the wildly despised Saban, this feels like an Alien v Predator situation: whoever wins, we lose.

The public potshots may be the result of veteran coaches adjusting to a shift in the power dynamics of college sports. NIL deals allow so-called “student-athletes” to make money from their fame and on-field success (which are typically, but not always, connected).

NIL wasn’t a move that the NCAA made willingly: it took a Supreme Court decision to force the organization’s hand. It’s a decision that has threatened the sport’s old guard, which is not used to players having any economic leverage whatsoever. And players with economic leverage are less willing to do everything their coach tells them, particularly if they feel they can find a better deal at another college.

Saban, after all, did not limit his attacks to Fisher’s program. Indeed he also called out Jackson State and the University of Miami, clearly concerned that the old way of doing things is on its way out. After claiming that his program didn’t “buy” a single player, Saban railed against how things have changed, “I don’t know if we’re going to be able to sustain that in the future, because more and more people are doing it. It’s tough.” He also conceded that his own players are making money – $3m total was his estimate – but that they are “doing it the right way.”

This is all an attempt to establish a moral high ground in an industry – and college football is very much an industry – where ethics are often sorely lacking. In practice, college football the “law” usually means whatever you can get away with. If Saban sounds unusually rattled, it’s because he’s no longer exactly sure what the rules are.

Saban has long had the advantage of selling recruits on what playing for Alabama mreans: they have a realistic shot at winning a championship every year and possibly even of making it to the NFL. It’s an advantage that programs like Texas A&M don’t have, so it’s easy to understand why the Aggies would seek out alternate ways to entice players – and it’s also easy to understand why Saban would feel threatened.

What schools can get away with is now changing in real time and, with different states having different rules governing NIL rights, the waters are more muddied than ever. It’s also possible that even elite head coaches are worried that power is starting to shift towards the players.

They need not worry on that front. No matter how much players’ newfound revenue changes the dynamics in college sports, the industry remains centered around the coaches that run teams like their own private kingdoms. After all, unlike in professional sports, players can only remain in college for so long and even star quarterbacks like Winston remain cogs – albeit crucial ones – in much larger systems. Maybe that will change one day, but chances are that it will be long after Saban and Fisher have moved on.