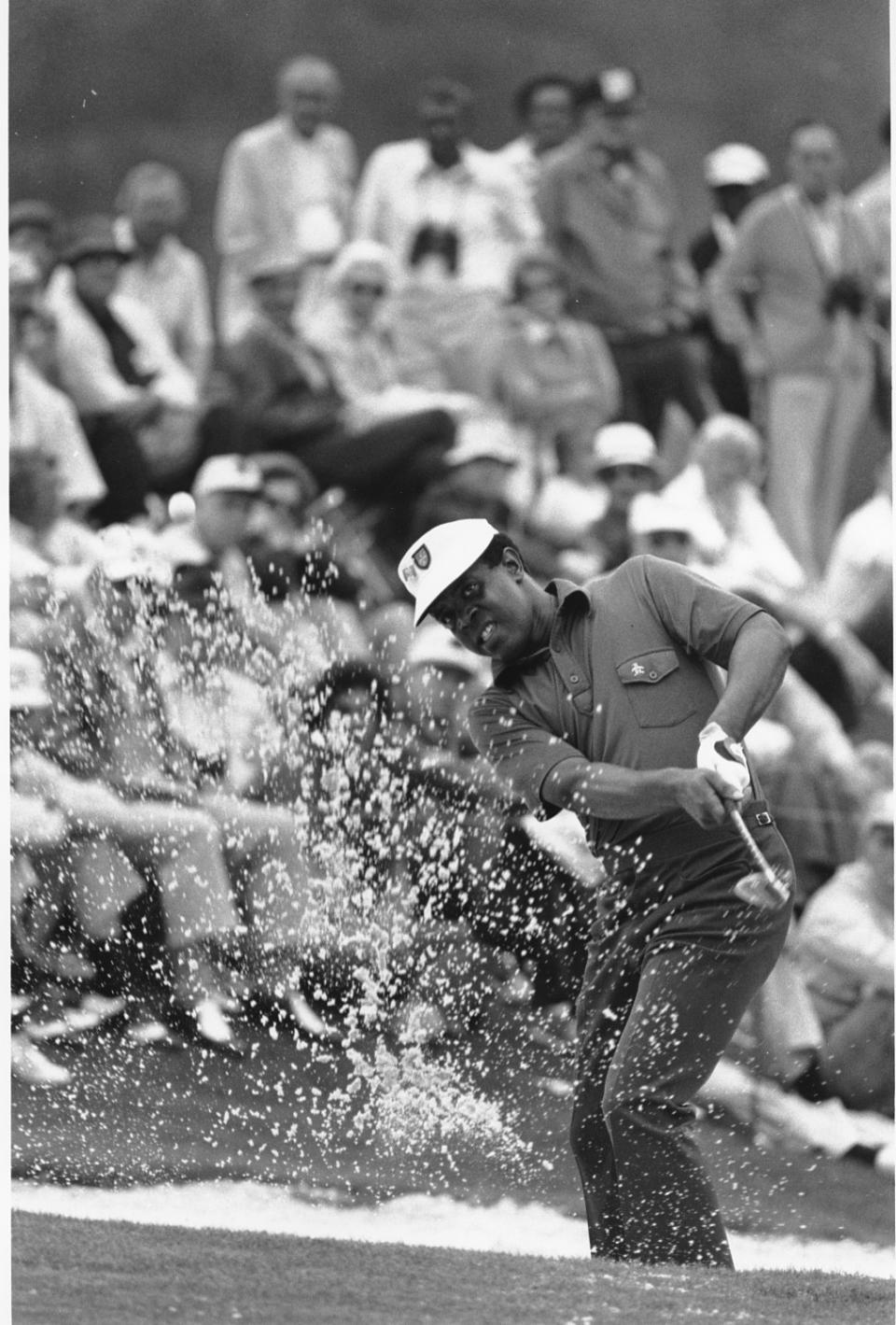

Lee Elder, who broke the color barrier, honored during Masters ceremonial tee shot

He marched on Washington for the “I Have a Dream” speech. He once searched in vain for his golf ball in Memphis after a spectator absconded with it. He strode briskly down the middle of a Florida fairway with an armed guard next to him and death threats rattling in his head.

Lee Elder will take part in a different walk Thursday. With dawn breaking and the sun peeking over the Georgia pines, he will step onto the first tee at Augusta National and — along with legendary golfers Jack Nicklaus and Gary Player — hit one of the ceremonial drives to open the most prestigious tournament in golf.

“I’m surely going to be nervous, there’s no doubt about that,” said Elder, 86, who broke the color barrier in 1975, becoming the first Black golfer to play in the Masters. “If someone says they’re not going to be nervous in the presence of Jack Nicklaus and Gary Player, with all these people watching, you have to be. I just want to make sure that first shot of mine goes straight.”

Elder, who lives in a senior community in Escondido, doesn’t have the combined nine green jackets of Nicklaus and Player — his best finish was a tie for 17th in 1979 — but his contribution to golf history is monumental. Friends and family from all over the country will ring the tee box to watch the shot.

“He’s hit millions of golf balls, but this one swing is one that’s really taking away the walls of division for people all over the world,” said Dave Scott, among his closest friends. “That’s the beauty of this.”

A few miles from Augusta National, at a public course that’s a favorite of the Black caddies who used to work the Masters, Elder’s impact is felt in a profound way.

“I’ll be in front of the TV,” said Curtis Smith, standing in the parking lot of the Augusta Municipal Golf Course, a place known affectionately as the Patch. “I won’t be playing no golf at the time. It’s very meaningful. To see him play the Masters, and now for him to be hitting a ball in that ceremony … that’s the top of my list right there.”

Elder was known for driving the ball laser straight, yet his path to prominence was anything but direct. It’s difficult enough to make it as a professional golfer. This was the late 1960s and early ’70s, and, because of the color of his skin, Elder had all sorts of other obstacles placed in his path.

“When I won at Pensacola, they had received calls that if I won the tournament I would never get out of there alive,” he said during a recent two-hour interview with the Los Angeles Times at his apartment complex north of San Diego. “So when I made the putt to win and I was going out to join my friends, Jim Vickers and Harry Toscano, they had beers in their hands ready for me. Jack Tuthill, who was then the tour supervisor, grabbed me and said, 'Hey, you can’t go out there.’ I said, 'Why can’t I?’ He said for me to get in the car so they could drive me back to the clubhouse. In the car, he told me about the threats.

“The ceremony was given inside the clubhouse. We couldn’t do it outside. That was the decision of the people there. I was ready to get my trophy and my check and get out of there.”

There were more threats. Once, on a par-five at Colonial Country Club in Memphis, a spectator ran onto the fairway, picked up his ball and threw it into the road.

“When I called for a ruling, they came down and people were heckling,” Elder recalled. “Everything about, 'What’choo doing? You’re giving that … a free drop?’ talking to the supervisor.”

Terry Dill, who along with Tommy Aaron was playing in the threesome, spoke up.

“Terry said, 'The ball was approximately here. We watched it from the tee and knew that it was in the fairway,’” recalled Elder, who eventually got a drop. “The next day, I had to play with a police armed guard. My friends came with me and had to walk in the fairway with me.”

Despite those memories of ugliness, Elder is warm, gregarious, and beloved by his fellow golfers. He’s not consumed by bitterness but overwhelmed by gratitude.

“I’m very excited about it, there’s no doubt,” he said of the ceremony. “To be able to walk up and take the place of the great Arnold Palmer [who died in 2016], to go up and step in his shoes — well, not step in his shoes because that could never happen — but just to be present, to be on the tee with these two giants, is going to be very exciting for me."

It was in November, at the Masters that had been postponed because of the COVID-19 pandemic, that Augusta National Chairman Fred Ridley announced the club would be honoring Elder for his trailblazing and courageous contributions to the game.

“He's had a rough ride,” Player said. “When you live the kind of lives that we've had and you think of the rough ride that he had, it was most appropriate to be asking him to do it.”

The club endowed two scholarships at Augusta’s Paine College in Elder’s name and pledged to cover all costs of the school’s men’s and fledgling women’s golf programs.

“We hope this is a time for celebration, and a time that will be a legacy, create a legacy, not only for Lee but for us that will last forever,” Ridley said at the time.

Elder did not attend Paine, a historically Black college, but feels a deep connection to it. When he made his Masters debut in 1975, he and a group of friends who had accompanied him from Washington, D.C., were denied service at an Augusta restaurant, ostensibly because of their race. Upon hearing that, Dr. Julius Scott, then Paine president, told the golfer and his friends that chefs from the school would be preparing them meals for the rest of the week.

“When I finished my first round, everybody that was not out on the course was lined up all along the clubhouse area to say, 'Thank you for coming, Mr. Elder.’ That was fantastic. ... I had to shed a few tears."

Lee Elder, on his reception after his first round at the Masters

That courtesy was among the spectacular memories for Elder that week. There were other poignant gestures of kindness.

Car dealer Jack Pohanka, who sponsored Elder, had 2,000 badges made and handed them out to Masters spectators, known as patrons. The pins featured a picture of Elder with the words, “Welcome to Augusta, Lee Elder. Good luck.” They were gone in hours.

“Everywhere you looked around in the gallery, on each and every fairway, you saw people with those buttons on,” said Elder, who repeatedly got standing ovations as he walked down the fairways.

Most moving to him was the reception when he finished his first day.

“It wasn’t from the patrons, it was from the workers,” he said. “When I finished my first round, everybody that was not out on the course was lined up all along the clubhouse area to say, 'Thank you for coming, Mr. Elder.’ That was fantastic.

“Here I was coming off after my first round and being greeted by a lot of the friends, a lot of the well-wishers. The line was so long. I was walking along, and all of a sudden I see all these people out there. I had to shed a few tears.”

Idyllic as that sounds, Elder still rented two houses in Augusta because of security concerns, so people wouldn’t know exactly where he was staying. He had qualified for the Masters with a tournament victory at Pensacola, on a course that once denied him entry to the clubhouse and made him use the parking lot to change into his golf shoes.

“I feel that several players should have been at the Masters before me,” he said. “You go back and look at Pete Brown, who won the Waco Turner Open in 1965. He was not invited. In 1967, Charlie Sifford won the Sammy Davis Jr. Greater Hartford Open. He was not invited.”

Sifford would win the L.A. Open in 1969. Brown won the Andy Williams San Diego Open in 1970. Still no invitations. So it was important to Elder to receive their blessing when he finally garnered a Masters invitation in 1975.

Although Sifford was standoffish, scarred by the repeated snubs, Brown warmly congratulated Elder, as did many other pros.

There was a push, led by New York Congressman Herman Badillo, to secure a spot in the Masters for Elder even before he won at Pensacola, but in the end the golfer himself didn’t want that.

“They asked me if I would accept it, and I said no,” Elder said. “The only way I wanted to go to the Masters and participate was by virtue of winning and qualifying to go the correct way. Not a special invitation because of my color, because I had a lot of friends that happened to be white that had a record equal to mine if not better. So how do you think they would feel? You think they would continue to be my friend if I accepted something like that?”

Elder and Player have been close friends for most of their lives. In 1969, they made an audacious trip to South Africa, Player’s home country, which was ravaged by racial division.

“He was put under a lot of pressure by certain groups here, and I was called a traitor,” Player said. “So he came down there, and must have been very nervous, and he had the courage to accept the invitation and come down there knowing what a great deed he would be doing. It was very influential because at that stage no Black visitors or people of any color were visiting South Africa.

“At that stage we still had a lot of young Black potential golfers, but they didn't have a hero, so to speak, and to have Lee Elder come down there was remarkable, and it went off extremely well.”

Elder had the official designation of goodwill ambassador by the U.S. government on the trip, and the two made stops in Liberia, Ghana, Uganda, Nigeria and Kenya before arriving in South Africa.

“I told the South African prime minister that I wasn’t coming to play before a segregated audience,” Elder said. “I said, 'If I’m coming to South Africa, I’m going to come play before a mixed audience.’ Also, the Blacks who didn’t have enough money to pay the fees to come in, they’re going to have to be able to come in for free, which they granted me.”

He regards it as one of the most gratifying trips of his life. And Thursday will be another — and one that has sparked a bit of that old competitive fire.

“The vice chairman called me the other day and said, 'How do you think you’re going to fare?’ ” he said. Then, with that playful laugh: “I said, 'Man, I’m going to out-hit both those guys by at least a hundred yards.’ ”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.