The Raptors Won a Championship and the Rest of the NBA Is in Chaos

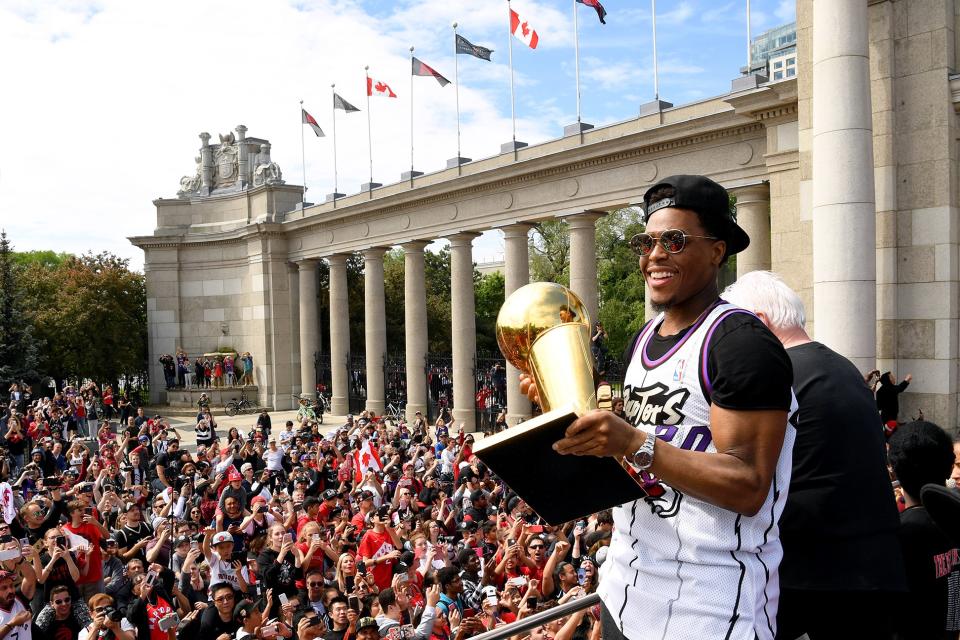

At least in Toronto, things are all right. Yesterday, thousands of Raptors fans and Canadian nationalists lined the city’s downtown to watch a parade for a championship that still seems like a dream. This title wasn’t supposed to happen, in the sense that it was neither predictable nor so magical that it felt prophetic and inevitable. Nor did it go to a team, or a city, known for outsized confidence and bravura, which would have helped it sink in. Nor does it help that the Raptors benefited from the injuries to Kevin Durant and Klay Thompson, or that they closed out Game 6 (and the series!) on a technicality. But there’s no wrong way to win it all— certainly, no player is wringing their hands over how they got a chip—and no matter how many times Toronto fans pinch themselves from here on out, this day will never disappear.

Things may be all right in Toronto (except the shooting that marred the parade), but the rest of the NBA is badly and inextricably out of joint. Darkness and chaos are not the same thing, and certain world religions, strains of self-help, and message board cults would have you believe that they are opposites. But there’s a difference between uncertainty, which can be exhilarating and fraught with possibility, and the sickening feel, plus attendant anxiety, that comes when things start to come apart at the seams. The bottom has fallen out, the hull has been breached, and you have to be pretty fucking thick to not be able to tell the difference between flying and drowning, even if on paper there are some similarities between the two. Chaos is liberating, maybe, but disorder cuts deeper. It unnerves us because it keeps us from ever feeling that things are all right.

When Kevin Durant’s Achilles injury was diagnosed, it sent proverbial shockwaves through the league, which is why nearly everyone paid to write about sports, or who aspires to be paid to write about sports, used exactly that phrase to describe the situation. Presumably, what they meant was that Durant was expected to be the major storyline of July’s free agency period, and that the de facto best player in the NBA would no longer potentially play a role in shifting the league’s balance of power. For at least a year, Durant’s offseason decision had been the most compelling narrative in the sport, as measured by the level of idle speculation, gossip-y rumor mongering, and athlete harassment, both online and in real life, that it prompted. What makes Durant’s injury so impactful, outside of just how heartbreaking it was, is the destabilizing effect it had on what we expected to see, and what resolution we hope to get out of the offseason. We have been gearing up for one thing, and instead of getting another, we have no idea what we will get instead.

1150409690

Ron Turenne/Getty ImagesDonald Rumsfeld, who was generally seen as a gruffy, cranky asshole when he helped set into motion a war that would kill hundreds of thousands of people, is now discussed in certain circles as a war criminal. The shift in perception from “the Bush administration were stupid” (a Bush-centric view) to “they were cynical and unfeeling” (the Cheney-centric, and correct, version) makes it easier to see Donald Rumsfeld as evil, or least evil in the way that it most frequently shows up outside of comics and true crime podcasts. The Iraq War and its endless aftermath were administered like cold-blooded corporatism, not the brain-dead nationalism many took it for at the time. But bad people can make important contributions to culture, which is why, whether or not he is a war criminal, Rumsfeld’s impromptu riff about “known knowns, unknown knowns, known unknowns, and unknown unknowns” is one of the most profound things anyone in the United States government has ever said, and feels far less icky when applied to sports than when used to frame up massive amounts of human suffering. “Unknown knowns” is the part of the equation so bizarre that you can get lost in it unless you default to the unconscious, which was probably not what Rumsfeld had in mind.

It’s “unknown unknowns,” though, that’s the most haunting, and gets right at what makes the NBA so eerie these days. We expected to see the Warriors phased out; this would actually open up the league and make it more interesting. Without Durant’s story off the table, though, it’s way less clear what we’re bracing ourselves for, and the degree to which the entire NBA is up for grabs is unsettling. There was some comfort in the authoritarian rule that the Warriors represented. We’re now facing a future that will feel incomplete, and indeterminate, until Durant returns—maybe even to the Warriors, which could in one year from now have us right back where we started from.

Even this weekend’s Anthony Davis trade, which had been telegraphed by LeBron James and Klutch Sports for so long that it was easy to forget that it hadn’t actually happened yet, opens up more questions than it answers, and throws things off in a way that’s more than a little bit uncomfortable. When James failed to make the playoffs this year with a young Lakers team that proved to be further away from legitimacy than was initially suspected, there was much hand-wringing over the changing of the guard, the end of an era, and the King have perhaps already started an inevitable, but still unfathomable, decline. Then, overnight, the entire Lakers roster was gone and replaced with one of the most dominant players in the league. If the franchise can land a marquee free agent this summer, they would likely be the favorites to win the first post-Warriors NBA title.

After one down year, James could once again find himself on top, and everything we thought we knew about his future could be replaced by an entirely different trajectory, not to mention one that obliterates all karmic payback for Lakers hubris and Klutch Sports’s less-than-savory presence in the Davis deal (anyone who has a problem with a player like James doing backroom dealings should examine their beliefs more closely). A lost season is very different than a season spent losing ground.

Maybe the Raptors’ title, too, is an indication that the NBA is not quite right at the moment and may not be again until 2019-20 wraps itself up in a satisfactory fashion. Whether or not Kawhi Leonard sticks around, Toronto is not expected to be repeat. That this team is currently the defending world champs isn’t a fluke—they did too much, too well, for too long to deny them credit—but as many people have already noted, this does feel like one of those one-off titles that often crop up in the wake of a dynasty, as with the Spurs’s 1999 ring that came in between the second Bulls’ three-peat and the Lakers’ Shaq/Kobe run, or Pistons’s 2003-04 win over a diminished version of the latter.

We’ve taken a break from the narrative and don’t know fully when it will pick up again. It may be incomplete, or unrecognizable, or take some time to come into focus. But we’ll get one soon enough. That we’re at a loss in the interim may not be the best thing. That we are wedded to narrative may incapacitate us in the short-term. But for better or worse, the NBA’s appeal depends on a certain amount of stability and constancy (as opposed to, say, March Madness, which revels in its lunacy). We want things to make a certain amount of sense.

Originally Appeared on GQ