One nerdy piece of good news about Omicron: We already have tests that spot signs of the variant

Because of the way the Omicron variant has mutated, some PCR lab tests can provide a good hint that it's around.

The clue is not definitive, but it can help scientists determine which tests to sequence, saving time.

It's possible that new PCR tests could be developed soon to more quickly screen for Omicron, without sequencing.

In the days and weeks before scientists in South Africa and Botswana found Omicron in early November, laboratory workers there started noticing something strange about many of the PCR lab tests being done to detect COVID-19.

Something was missing. One of the genes their tests typically targeted to find out whether a person had the virus was not present. The coronavirus's "S" gene was dropping out.

This didn't lead to any false negative tests, because there are two other gene targets that were still successfully lighting up. Still, scientists started to suspect maybe something strange was afoot.

"All of a sudden, this S gene fallout was just in basically every single sample," Vicky Baillie, a senior scientist at Wits Vaccines & Infectious Diseases Analytics Research Unit in South Africa, told Insider. "We then did the sequencing, and that's when we found this new variant."

It turns out that one of the standard laboratory tests that many scientists around the world use to screen for the coronavirus can provide an early hint that Omicron is around.

Knowing this gives disease-watchers worldwide a head-start, helping them decide which samples to put through the costly and time-consuming genetic sequencing process to confirm the new variant has arrived.

How one brand of PCR test detected Omicron

The fact that the S gene was missing from many South African lab tests wasn't a definitive sign that Omicron was there, but it was a kind of accidental early alert system.

It was detected through one of the common brands of PCR lab tests: the ThermoFischer TaqPath COVID-19 combo kit. Other PCR brands have tests that work in a very similar way, but they may target different gene combinations that are more well-preserved with the new variant. No authorized coronavirus test, so far, has been deemed unusable for Omicron, according to the US Food and Drug Administration.

"We believe high-volume polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and antigen (rapid) tests widely used in the US show low likelihood of being impacted and continue to work," the FDA said in a statement Tuesday.

But not all PCR tests can sound the alarm about Omicron, because "it's not what their job is," Scott Becker, CEO of the Association of Public Health Laboratories in the US, said on Tuesday during a media briefing. PCR tests are designed to diagnose any and all COVID-19, not to tell people exactly which variant they have.

Still, PCR is faster, cheaper, and easier than whole genome sequencing, making it a potentially great tool for large scale variant screening. It's a shortcut that can, in turn, improve how nimbly policymakers, pharmaceutical companies, and scientists respond to new disease threats.

US labs are racing to stock up on the same PCR test used in South Africa

ThermoFischer's test is such a useful tool for hunting down this variant that the bulk of public health labs all across the US are all racing to use it "for the next two weeks, just to have this heightened screening while we look for Omicron in the US," Kelly Wroblewski, the director of infectious diseases for the APHL said during the briefing.

Of the 68 public health labs in the country, 56 are capable of using this specific test. This will be "really really helpful" for US Omicron surveillance, Wroblewski said.

Because it takes roughly 24 to 48 hours to sequence a coronavirus sample after testing it, having an earlier indication of which tests might potentially be Omicron positive is a nice perk. But it's definitely not a perfect shortcut. At least not yet.

"This is a fairly common mutation," Wroblewski added, explaining why these PCR tests on their own can't be used as "a definitive tool."

The same kind of S gene dropout happened previously with the B.1.1.7 variant, aka Alpha, and it has with other, less significant coronavirus variants too.

"It just helps guide you that you might have something of interest that you want to interrogate a bit further," Wroblewski said.

Scientists can build more specific PCR tests — and they could be ready in 6 weeks

Dr. Charity Dean, a former top public health official in California who was one of the first people sounding the COVID-19 alarm to the White House, calls the S gene dropout "an early signal of where we think Omicron is in the world."

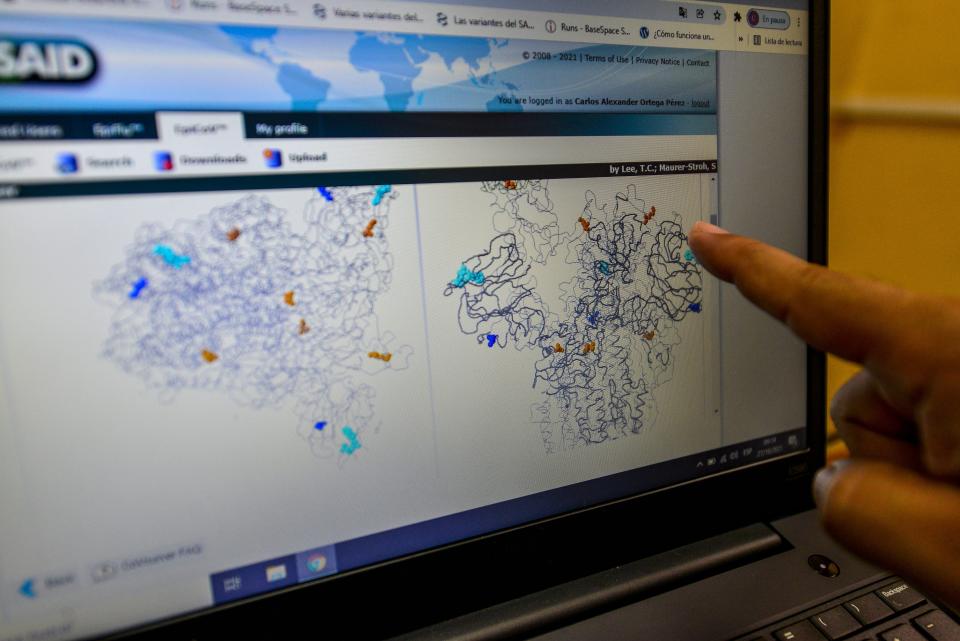

"But really, you need to do whole genome sequencing to confirm that, and that capability is limited just because of the cost and the investment it takes for a lab to do it," said Dean, whose new venture, The Public Health Company, runs a genetic sequencing lab to improve disease surveillance in the US. "It's not something they can just stand up overnight."

Though the PCR tests we have today can't definitively screen for Omicron, Dean said it's possible that because of the vast array of new mutations that Omicron exhibits, new tests could be designed to do that very soon.

"You can actually build a PCR test to target a specific variant," Dean said. "I would anticipate we'll have that for Omicron, probably in six weeks."

Until then, other countries can benefit from the same lucky break that South Africa did, by combining S gene-targeted PCR testing with top-notch sequencing work, to more quickly figure out if this variant is at hand.

"In comparison to a lot of other African countries, and even to a lot of first world countries, we do sequence a lot," Baillie said. "I think it also came down to the [PCR] assay that we happened to be using."

Read the original article on Business Insider