Nuclear bomb detectors sniff out another find — a new group of blue whales, study says

Dr. Emmanuelle Leroy of the University of New South Wales, Sydney, was analyzing nuclear bomb detector data for her work as a bioacoustician — people who study the relationship between animals and sounds they make and hear — when she noticed “an unusually strong signal” occurring in a strange pattern.

“At first, I noticed a lot of horizontal lines on the spectrogram,” Leroy said in a statement. “These lines at particular frequencies reflect a strong signal, so there was a lot of energy there.”

She tried solving the mysterious discovery by examining nearly two decades of underwater microphone data, available through The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization, which uses advanced microphones deep in the ocean to detect potential nuclear bomb tests and prevent development of more powerful explosives. Leroy studied the frequencies, tempos and structures to look for wider patterns that might reveal the source.

It turns out the “songs” were coming from an apparently elusive new group of pygmy blue whales — one of the largest animals in the world — never before seen in the middle of the Indian Ocean where their songs were detected.

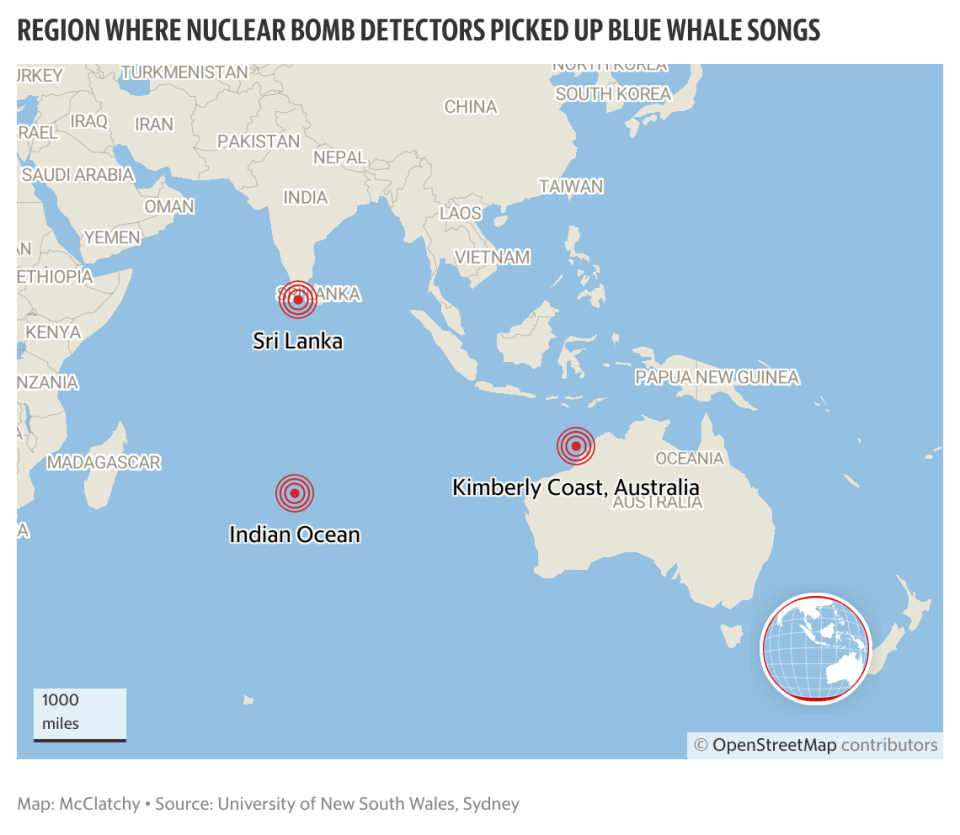

The beasts’ vocalizations were also detected “as far north as the Sri Lankan coastline and as far east in the Indian Ocean as the Kimberley coast in northern Western Australia,” Tracey Rogers, a marine ecologist at UNSW and senior author of the whale study, said in the statement.

“Thousands of these songs were being produced every year. They formed a major part of the ocean’s acoustic soundscape,” said Leroy, lead author of the study and former postdoctoral researcher at the university. “The songs couldn’t have just been coming from a couple of whales — they had to be from an entire population.”

Researchers compared the acoustic compositions of the songs with that of three other blue whale song-types that are heard in the Indian Ocean, as well as with four types of Omura’s whale melodies in the same region.

Evidence shows the music belonged to no other whale in the aquatic neighborhood, suggesting the group it came from is a new one that has managed to remain unseen, despite the species being about two standard buses long.

Although the discovery still needs to be confirmed with visual sightings, which researchers say can “be tricky and expensive to fund,” it’s a win for marine conservation.

Blue whales went nearly extinct after the whaling boom in the 20th century and haven’t been able to up their numbers unlike other whale species in the Southern Hemisphere. Researchers estimate that less than 0.15% of blue whales in this region survived whaling.

The new population, named “Chagos” after the group of islands their songs were detected near, would be just the Indian Ocean’s fifth group of pygmy blue whales if confirmed, according to the study published in April in the journal Scientific Reports.

“Blue whales in the Southern Hemisphere are difficult to study because they live offshore and don’t jump around — they’re not show-ponies like the humpback whales,” Rogers said. “Without these audio recordings, we’d have no idea there was this huge population of blue whales out in the middle of the equatorial Indian Ocean.”

Blue whale songs are like human slang

The songs of blue whales can travel anywhere between 125 to 310 miles underwater, yet they remain mostly inaudible to the human ear. Unlike humpback whales, for example, which are “like jazz singers” that change their songs all the time, blue whales like more structure, Rogers said.

Even so, different blue whale populations are known to diversify their melodies from time to time, “similar to generational slang between humans,” according to the UNSW release.

What’s more, these songs can teach scientists about the animals’ population, spatial distribution and migration patterns..

“We still don’t know whether they’re born with their songs or whether they’ve learnt it,” Rogers said. “But it’s fascinating that within the Indian Ocean you have animals intersecting with one another all the time but whales from different regions still retain their distinctive songs.

“Their songs are like a fingerprint that allows us to track them as they move over thousands of kilometres.”