‘We’re not gun nuts who make films’: who are Hollywood’s armourers?

Film and television armourer Rob Partridge is packing up his weapons after a day’s filming when I call him – a laborious process that he compares to moving house. “I get people who want to do this job because they think it’s a lot more exciting than it is,” he says.

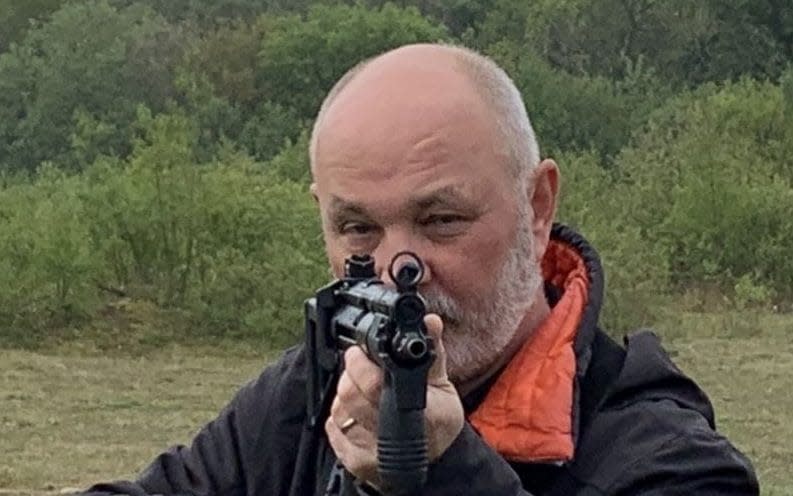

Rob Partridge is the director of Perdix armoury service and has worked on film and TV productions for more than 30 years – British productions that range from EastEnders to Skyfall. He namechecks his work on Gareth Evans’ Gangs of London more than once and is currently working on a major project over which he’s sworn to secrecy. (A cursory glance at IMDb reveals that it’s the Tom Hardy-starring Netflix actioner, Havoc.)

The role of working guns on film sets is being scrutinized following the death last week of cinematographer Halyna Hutchins. Hutchins, who was just 42, died during rehearsals of the Alec Baldwin western Rust, after Baldwin was handed a gun loaded with live ammunition.

Questions have been raised about the film’s head armourer, Hannah Gutierrez-Reed – who admitted she was “nervous” about becoming a head armourer – and the assistant director Dave Hall, who gave Baldwin the gun.

Authorities have revealed that the investigation seized various ammunition, including “two boxes of ammo”, “loose ammo and boxes”, and a “fanny pack with ammo”. Reports also say that crew members may have been using live ammunition to shoot beer cans just hours before the accident.

According to Rob Partridge, that sort of accident wouldn’t happen on a British production. “In the UK we don’t have live ammunition on set,” he says. “If you rang up an armourer and asked, ‘What live ammunition do you have?’ They’d say, ‘We don’t have any!’ We don’t keep it. We don’t need it.”

The only time live ammunition goes near an armourer’s gun is if the gun is new. They might shoot a few hundred rounds – at an empty range and with a license, Partridge adds – to “loosen” it up. “You wear it in and it gets rid of any bearing surfaces that are slightly abrasive,” he says.

Guns are then modified to fire blanks and sent to a proof house for approval.

There’s currently no official, legislated route to becoming a British armourer. Though it tends to follow a process of “apprentice-journeyman-master,” says Partridge. “You can’t just appear on a film set.”

It is common for armourers to have military or police backgrounds. Partridge served 20 years with the British Army Reserves and did tours of Kosovo, Sierra Leone, and Iraq. “What you get from the army or police is a discipline with weapons – an understanding of procedures,” he says.

Also useful are backgrounds in camera work. “We’re in the business of making films,” says Partridge. “We’re filmmakers who happen to have guns, not gun nuts who happen to make films.”

Partridge estimates that he’s been on 4,500 sets. Partridge references a recent production: “30,000 rounds, not a scratch”.

In 2005 he tried to set up a training course for official certification but couldn’t get the proper support. Armourers, he says, are at the centre of a venn diagram that includes the Home Office, the National Rifle Association, pre-vetting organisations, Health and Safety, the police, and the Royal Military College of Science.

“There are all these people that can touch us but no one who can take ownership,” he says. “I’ve said we need someone to give us authority. But there isn’t anyone – I suspect that might change.”

Partridge holds a Section 5 Firearms Licence – the licence required for armourers to have under British law. “You don’t get handed them as you’re walking out of the Job Centre,” he says.

Applicants must demonstrate to the Home Office that there’s a need to be issued a Section 5 – and there are stringent checks.

“Police and security services will look into whether you’re prone to blackmail, look at your health records, and your criminal record,” says Partridge. “You have to be like Caesar's wife. You won’t find someone with a Section 5 who’s been in prison for a length of time. It just doesn’t happen.” Other key criteria include the security of weapons themselves. “The Home Office has very specific prescribed ways of how they have to be stored,” says Partridge.

Since last week’s horrific accident, a recent interview with armourer Hannah Gutierrez-Reed has surfaced, in which she talked about her previous film, the Nicolas Cage western The Old Way – her first job as head armourer.

“You know, I was really, really nervous about it at first, and I almost didn’t take the job because I wasn’t sure if I was ready but, doing it, like, it went really smoothly,” she told the Voices of the West podcast.

Gutierrez-Reed graduated in cinematography and film production from Northern Arizona University just last year and considered an acting career before she followed in the footsteps of her father – the legendary armourer and stuntman Thell Reed. A source from the Rust production told The Daily Beast that she was “inexperienced and green”. The Actors’ Equity Association’s guidelines state that guns should be test-fired off set before each use – by the armourer or an experienced person under supervision.

In the UK, someone who was inexperienced would not be issued a Section 5, says Partridge, though they could potentially be employed by a license holder.

“In all fairness if you don’t worry every day, you shouldn’t be there,” he says. But he clarifies: “In order to do this job properly, we worry about everybody every day. That’s a world apart from not feeling up to it or not being competent.”

Actors are allowed to handle firearms under Section 12 of the firearms act. They can handle firearms for the production and the production only.

“For training at the beginning, for the movie bit – the shoot, for the want of a better word – and anything needed in post-production,” says Partridge. “Outside of that, you are not allowed to touch it – same gun, same person. You can’t go out to the range and say, ‘I fancy a few bangs with that!’ It’s not allowed.”

Another part of the Firearms Act – Section 21 – takes precedent. It disqualifies people who have received prison sentences of three years-plus from handling guns at all. “End of story,” says Partridge.

Like all filmmaking, working as an armourer is a collaborative process. Rob Partridge begins by reading a script three times: first for the story, second to iron out continuity issues – to “debug it” – and thirdly to match characters with their guns and ammunition. “I think, ‘What do I know about this guy? What sort of gun would he have?’” says Partridge. “I sit down with the director and designer to get the feel and look. You then have to get the right number and versions of guns.”

This could include rubber versions – of varying hardness, depending on the action needed (such as clobbering another actor over the head or leaping around gun in-hand) – and there could be multiple versions of a working gun.

“You might need one that fires a huge flash and one you can put next to someone’s temple and squeeze and nothing comes out,” says Partridge.

The term “prop gun” is perhaps a misnomer. Working guns – “practical guns” – are real but modified to fire blanks. There are also rubber ones and “air softs” – which are also capable of pumping out air and therefore a projectile too. “Practical guns go ‘bang’, non-practical guns don’t,” says Partridge. “Our weapons are like different golf clubs – you use different ones in different situations to create the right effects.”

Partridge is also keen to point out that rigorous training is put into place. “Everyone who touches one of my guns gets trained,” he says. “They might be trained already but they have to go through me to make sure I’m satisfied.”

In the wake of Halyna Hutchins’ death, actors have spoken out about guns on set – and how the atmosphere changes when a gun is brought out. “There’s no doubt,” says Partridge. “Because it’s so serious – everyone gets serious about it.”

The question now, in the wake of a very real tragedy, is why are real guns used at all? “There are a couple of reasons,” says Partridge. “They certainly generate within the artists a different performance. However good you are, standing around going ‘bang bang bang’ is very different to holding an assault rifle belting out 900 rounds a minute. It changes the performance. There’s no question of that. There’s a visual reason too – the front-end flash, the cases flying, the gas and smoke.”

Part of the armourer’s job is to help with the choreography of scenes and ensuring artists and crew are in safe positions – a collaboration with stunt coordinators, the director, assistant director, and camera grips. “We’re on set every day there’s a gun and we’re there the whole time,” he says.

Actors and crew are moved away from the field of discharging cases. Camera operators are protected by a polycarbonate housing around the camera. Cast and crew will also wear ear plugs. Scenes are rehearsed with rubber guns. “If at any time we’re not happy, we say no,” says Partridge. “Given we have guns, we can walk off set. But we don’t do that. We say, ‘No we can’t do this, but we can do this.’”

There is also a specific process of getting firearms from the armoury to the actors’ hands. “They come out of the armoury, they go into the vehicle – in a special locked box – that goes onto the set with us, and then it goes to the artist,” says Partridge.

Before the exchange to the actor’s hands, two armourers check the barrel. “Both of us will check in case any foreign bodies have got in there,” says Partridge. “What can happen is if there’s a lot of dust, fake snow or grit, stuff can get in the barrel – it might jam the gun or fire grit towards somebody. We go to the artist, show them the gun, show that it’s empty, and say, ‘Here’s the gun you’ve been practicing with all afternoon, we’re putting five rounds into it.’ By now this is not their first rodeo.”

On the set of Rust, first assistant director Dave Halls handed Alec Baldwin and shouted “cold gun” – indicating there were no live rounds.

“He’s supposed to be our last line of defence and he failed us,” a Rust source told The Daily Beast. “He’s the last person that’s supposed to look at that firearm.” Hall was reportedly fired from a 2019 production following another accident involving a gun.

Rob Partridge says the relationship between armourer and first assistant director is “a critical one” (“The director comes to me for artistic stuff, and the first assistant comes to me for the management of it”) but the assistant director wouldn’t handle working guns on UK productions.

“There’s a system,” says Partridge. “The first assistant director will say, ‘final check’. Costume and makeup make sure the artists are 100 per cent right. But there’s a second queue for the armourer. You’ll say ‘armourer’s in’, then ‘weapons hot’, then ‘turn over’. The action takes place – ‘bang!’ – then the magic word ‘cut’ happens. The next thing you’ll hear is ‘armourer’s in’ again. No one else will get anywhere near the artist. You might have had a jam, the gun might still be dangerous, i.e. there’s a live round in it. We go in and the next thing you’ll hear is ‘gun clear.’ The retrieval of the weapon – the checking after the take – is possibly the most dangerous time because everyone thinks it’s over and it isn’t.”

Even firing blanks is dangerous – debris collecting in the muzzle, or hot and sharp cases flying out of the gun. Partridge tests every type of blank in every calibre of gun by shooting it at a piece of paper, and moving back until it no longer leaves a mark on the paper. If the “safety distance” is 10 metres, they double it – any crew in potential firing range are moved 20 metres away. They also now use UTM cartridges where possible – a safer kind of blank for close ups and head shots.

Another danger is people getting tired. “Particularly on a night shoot,” says Partridge. “When it’s 4am, that’s when we earn our money. You need the moral courage to say ‘no this isn’t safe, we have to do it differently’ to 200 people who want to go home. As an armourer you need the ability to accept your own decisions and make unpopular decisions.”

Partridge counts Ciaran Hinds, Edward Woodward, and Jeremy Irons among his favourite stars to work with. He also worked with Davie Bowie on the 1999 indie film, Everybody Loves Sunshine. “David Bowie was fun,” he says. “He had to have a gun pointed to his head.” Though he points out it was a supporting artist, not him personally, holding a beretta held to Bowie’s head.

Armourers' roles and practices may change in the US – there have been calls to ban guns from Hollywood productions entirely. There is, as Partridge says, a “gun culture” there that we don't have. Though he still maintains there should be a recognised course put in place here.

“I think what there needs to be is some kind of training certification,” he says. “So you know there’s an element of basic training.”