Play-action gives Jets extra dimension

Also in this article:

Next Surveillance:

Colts

More NFL:

Editor's note: Yahoo! Sports will examine the biggest weakness from the 2009 season for every team and explain how the franchise can address the issue. The series continues with the New York Jets, who finished second in the AFC East (9-7).

Biggest problem in 2009: A one-dimensional offense unfit for shootouts

The strength of the Jets' rushing attack makes play-action all the more effective.

(Donald Miralle/Getty Images)

New York Jets first-year head coach Rex Ryan got his team to within 30 minutes of the Super Bowl by playing a type of football that his father, Buddy, would appreciate. Using a brutally effective running game behind a dominant offensive line and the best defense in the NFL, Ryan's Jets established a tough, swaggering identity that was very old school. The Jets led the NFL in regular-season rushing attempts (607) and ranked last in passing attempts (393). Rookie Mark Sanchez(notes) had the third-fewest passing attempts in the last decade among quarterbacks with at least 15 starts, and the team's pass-run ratio of 0.70 was the 10th-lowest since the advent of the 16-game schedule in 1978. The Jets ran the most of any team in situations you'd imagine, but they also ran 45 percent of the time (most in the league) when behind in the second half.

This one-sided play-calling led to a series of safe wins, but left the offense ill-equipped to deal with opponents capable of getting past that great Jets defense and scoring serious points. Including the AFC championship loss to the Colts, the Jets were 0-6 when allowing 20 or more points in a game. That's a scary number in an NFL that gets more passing-based and explosive every year, as the New Orleans Saints could tell them; they scored 24 points in a victory against the Jets last season. The eventual Super Bowl champions allowed 20 or more points 13 times through the postseason, and went 10-3 in those games. The Colts were 4-3 under the same circumstances.

The need for a more varied and dynamic offense was obvious, and the Jets did their best to address the issue in the offseason with a couple of big personnel hauls. Free-agent running back LaDainian Tomlinson(notes) still provides a valuable option in the screen game, and the trade for Pittsburgh Steelers receiver Santonio Holmes(notes) gives the Jets the kind of medium-to-deep production they had with Braylon Edwards(notes) last season, without all the drops. The scene is set for the Jets to be more balanced, and it all starts with the quarterback.

The 2010 solution: Use play-action for a seamless transition to the 21st century

Sanchez had a lot to learn in his first professional season, but one thing he had from the start was a preternatural ability to sell play-action. This had its roots in Sanchez's collegiate days on a pro-style offense at USC and blossomed with the Jets' strong rushing attack. With defenses understandably tilted to stop the run, fakes to the backs were going to be very effective. Many young quarterbacks can turn those seemingly simple mechanics into a debacle. Not Sanchez, who was always fluid and convincing with the fakes. The Jets went with play-action on 25 percent of their pass plays, fourth-highest in the NFL, and they averaged 6.4 yards per pass play or scramble when they used it, as opposed to 5.5 when they didn't.

Sanchez had 13 regular-season pass plays of 20 yards or more in play-action, and two of them went to receiver Jerricho Cotchery(notes) in a Week 2 victory against the New England Patriots. After going 3-of-5 for 15 yards in the first half (minus-2 if you include a 17-yard loss on a sack), Sanchez opened up and hit Cotchery for passes of 45 and 22 yards in the third quarter. The 45-yarder came on the first play of the second half, and set things in motion for the offense. The fake did what it was supposed to do, forcing Patriots middle linebacker Gary Guyton(notes) to hesitate for a split second, and though Guyton was dropping into coverage, that split second was all that Sanchez needed.

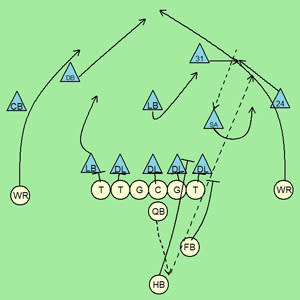

On the play, the Jets had first-and-10 at their own 44-yard line. Cotchery (89) was lined up wide right, and the Jets had an offset-I formation with a six-man line. This was another aspect to New York's successful use of play fakes – they'd frequently use run-action, firing their linemen out in run-blocking looks to add to the deception, and they did so on this play. The fake to halfback Thomas Jones(notes) behind the line of scrimmage gave Guyton pause, and Cotchery the free release at the second level to haul the ball in at the New England 38. That's about where safety Brandon Meriwether (31) and cornerback Jonathan Wilhite(notes) (24) crashed into each other as they converged on Cotchery, letting the receiver slip through and continue the play until Guyton finally brought him down at the 11. After a 2-yard Thomas Jones run, Sanchez used play-action again to find tight end Dustin Keller(notes) for a 9-yard touchdown.

The Jets' aerial attacks won't ever be mistaken for the Colts or Saints. That's not what they're good at, and it's not what they want to do. The 2010 Jets want to marry their smashmouth approach to a passing game a bit better than "just good enough," and putting Mark Sanchez in different play-action scenarios is key to making that happen.