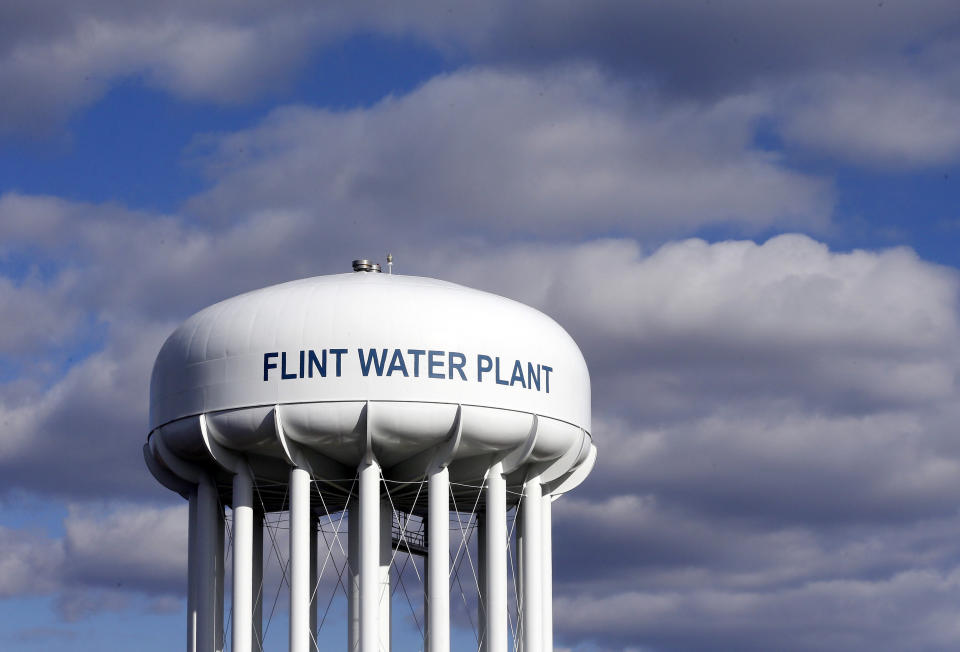

'Why won’t you come to Flint?' NFL's Demario Davis, Josh Norman respond to water crisis

Demario Davis had assumed it was over. So did Josh Norman.

But like so many in this country, both NFL players were shocked to learn that life in Flint, Michigan, still had not returned to normal.

The water crisis remains ongoing.

The first-hand accounts from local residents painted a potentially bleak picture for an impoverished community that has lost faith in its local government. Their stories were hauntingly similar — those of families still in need of assistance, still struggling to survive, still waiting in vain for clean tap water.

“The people have just given up,” Davis, a linebacker for the New Orleans Saints, said in an early morning telephone interview with Yahoo Sports. “They don’t even want to talk about water anymore. Because they’ve cried for so long about water that they’ve just learned to operate with bottled water.”

[Best bracket wins $1M: Enter our free contest now! | Printable bracket]

It’s a little past 7 a.m. Tuesday when Davis recounts the stories of the poor, the overburdened, the forgotten. Young children, pregnant women and old people unwittingly drinking contaminated water. There was even the tale of a heartbroken boy who had encouraged his sister to drink water instead of sugary juices, only to learn that he had been “poisoning” his younger sibling all along.

Davis detailed the dizzying array of issues plaguing a city that has been polluted by insidious corrosion in many forms.

“It’s almost like Russian roulette: Do I have lead in my water or not? They have no way of knowing,” said Davis, who arrived in Flint Monday morning with Norman, the Washington Redskins’ star cornerback, for their 48-hour mission.

The pair — which generated headlines last June when they flew to San Antonio to give out backpacks, books and toys to children who had been separated from their parents near the United States-Mexico border — partnered with the United Way in order to create a project fund to assist Flint’s 96,000 residents.

Told that one truck delivers 2,000 cases of water three times a week (on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays), Davis and Norman met with locals for two hours on Monday and loaded up a rented U-Haul truck with about eight pallets, each of which carried 50 cases of water.

In Flint, Michigan trying to provide aid to those in need. The water crisis continues. pic.twitter.com/4edZv4DJ3m

— Demario Davis #56 (@demario__davis) March 19, 2019

“We wanted to know what it was like to live in Flint,” Davis said Tuesday morning, before they visited local schools and delivered water to families and residents who are unable to drive to the truck sites on their own.

“You can assume something’s bad, but it’s even worse than you can imagine, knowing that this is going on in our country,” Davis said. “So we just wanted to figure out how can we mobilize? We just wanted to help out as much as we can. Our greater goal is to be able to use our platform to help their cry be heard across the country.”

It’s unclear when this nightmare will end for Flint residents, but one thing is clear, Norman stressed.

“This community here is strong,” the Redskins cornerback told Yahoo Sports in a separate interview Tuesday afternoon, just a few hours before he and Davis were set to board evening flights back to their respective homes. “And they help. And the way they help, it is big. Because in communities now, no one’s going to do it unless they do it. And that’s something to be proud of.”

A call to action

Davis and Norman are no strangers to community outreach.

As members of the Players Coalition — a task force comprised of 12 NFL players aiming to impact social justice and racial-equality reform at federal, state and local levels of government — both players routinely use their platforms and their resources in an effort to effect change in various communities.

That’s what led the pair to peruse the aisles of a San Antonio Walmart at 3 a.m. last summer. They spent those early morning hours filling up carts with toys and book bags they later donated to immigrant children who were separated at the border from their parents and later released from family detention centers. In response to President Donald Trump’s “zero-tolerance” immigration policy — which resulted in more than 2,500 migrant children being separated from their parents at the border — Davis and Norman felt compelled to act.

The feedback from that Texas trip was overwhelmingly positive, Davis said, but there was one message that routinely popped up on their Twitter timelines.

“‘Why won’t you come to Flint?’” Davis recalled. “And we were like, ‘That’s weird. I thought the water crisis was over.’”

“I thought it was over with too,” Norman said. “This is crazy.”

Flint’s water crisis began in 2014, but five years later, Michigan officials still can’t pinpoint the location of all the lead pipes throughout the city that need to be replaced with safer copper pipes. Compounding matters is the financial burden placed upon already-impoverished inhabitants. Residents pay some of the highest water rates in the country, yet the median household income in Flint was $26,330 between 2013-17, while an estimated 41.2 percent of residents live in poverty, according to U.S. Census data.

“Plus, people have been told for five years that the water is good. They’ve covered it up for so long, so none of the people trust them,” Davis said, referring to government officials. “So imagine not being able to wake up in the morning and brush your teeth because you can’t use the water. Imagine you can’t take a shower because you can’t use the water. You can’t get a cup of ice. You can’t — do anything. I think we take for granted how essential water is.”

“In a week’s time, a family of four needs about 18-20 cases of water. They’re operating on four to six cases,” Davis said, highlighting the fact that “the water is good” on the outskirts of the city. “Imagine having to tell your kid: Go take a bath, but you have three bottles of water apiece. You’ve gotta find a way to make it work. Imagine trying to cook a meal and you can’t use water. You can’t clean your vegetables. You can’t boil water because that makes the water worse. You have to use bottled water. To make a hot dog. Noodles.”

Davis’ $10 challenge

Their collective goals beyond the gridiron are clear.

To listen. To serve. To effect change.

But Davis’ objective for Flint is more precise.

“If a million people gave $10, that’s $10 million that’s going to go directly to people who are in need of bottles of water, filtration systems put in their houses — one of those is $3,000 — that can purify the water as a temporary solution,” said the Saints linebacker.

With the community relying on the charitable efforts of nonprofits, both players are hoping their voices will help keep focus on Flint.

“We want to do our little part first, but we also have a tremendous platform so we want to campaign for these people and advocate on their behalf and amplify their cries to make sure that they’re being heard,” Davis said. “It’s important for us, as people, to always rally around where there’s a need. We can always do something. That’s part of being human — we have the ability to empathize. So put yourself in someone else’s shoes. No, the problem won’t be solved in a day. But everybody can do a little something every day until that problem is gone.”

Unlike his Players Coalition partner, Norman said he doesn’t have a target in mind for monetary donations. Instead, he’s just anxious to see their efforts result in visible changes in the area.

“We can get trucks until the cows come home but it’s not going to fix the water,” Norman said. “The problem is the pipes. So we’ve teamed up with them so we can try to talk to city council members to see when they’re going to be placing these pipes back in the ground because it’s freezing right now. … And the fund that we do have is going directly to the community and aid in their efforts to fill in the pipe holes to where it can be a faster and more efficient process. This stuff was supposed to be finished two years ago and it’s still an issue.”

By 2:30 p.m. Tuesday, there was a line of cars stretching down the street from where Davis and Norman’s U-Haul was parked. Norman estimated there were at least 150 cars waiting.

“That’s how bad they don’t trust the water,” said the cornerback, who was at a loss for words when a man made two separate trips to collect 12 total cases of water from their truck. “Because they trusted it before and then they found out it was bad.

“It is crazy that it’s still a crisis.”

More from Yahoo Sports: