Once a Dodger, Mike Piazza cemented his Hall of Fame legacy as a Met

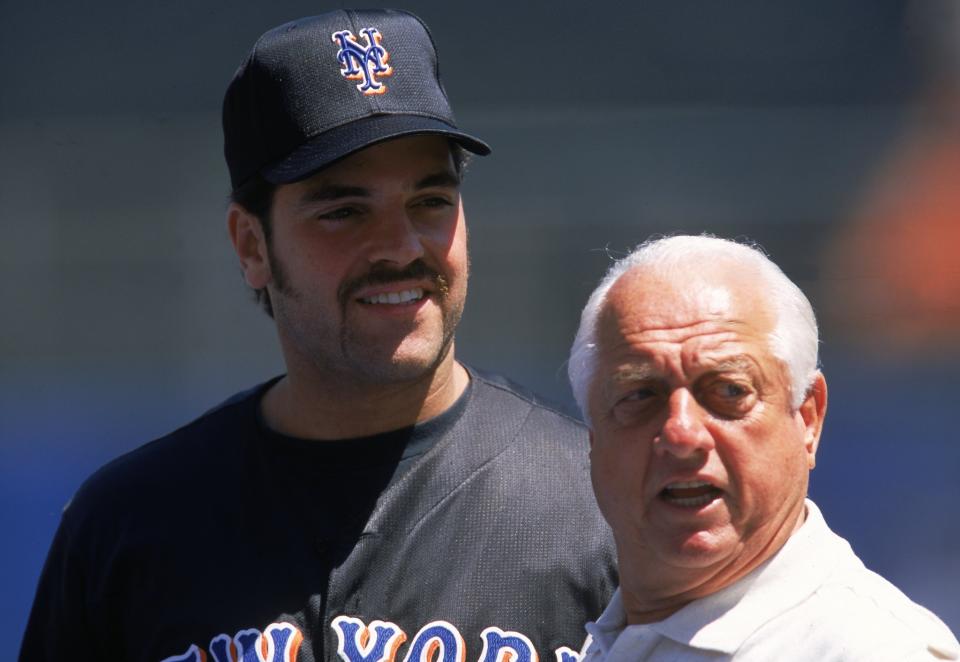

He called everybody dude. He already walked stiff, like his knees or hips or ankles didn’t bend right. He went along with all the stuff Tommy Lasorda said, the goings-on about the size of his forearms for one, and the stuff Tommy Lasorda did, like cuff him on the back of the head as though he were still a shaggy-headed 12-year-old. He signed a box of baseballs for an umpire in the trainer’s room at Shea Stadium one morning, and afterward he smirked and shrugged and said, “Whattami gonna do, say no?”

Mike Piazza was a star by 1996, this in a town that knew what stars looked like, that lived among them. He was 27 years old, making life-changing money for the first time, playing baseball on his bat barrel. He caught a staff known then as the International House of Pitchers — Hideo Nomo from Japan, Ismael Valdez from Mexico, Ramon Martinez and Pedro Astacio from the Dominican Republic, Chan Ho Park from Korea and Tom Candiotti from California, and hardly anybody griped. On a rainy night in Denver, on a mound so slick his pitcher opted to ditch his windup completely, he caught a no-hitter, and when he raced out to celebrate found the restrained Hideo Nomo would require some encouragement. Nomo finally raised a shy fist.

(Indeed, in the postgame news conference, Nomo’s stoicism was offset by a reporter — and countryman — who’d come to the states to cover him, and in the rear of the room loudly sniffed back tears of joy.)

The season ended with three games against the San Diego Padres, a tight NL West race to be decided over a weekend in L.A. The winner would enter the postseason as the division winner, the runner-up would go as the wild card, and there had been debate over which avenue would be more beneficial.

“Maybe,” Piazza sighed, “the winner can get a bowl of fruit or something.”

The Padres won the division, the Dodgers were the wild card, and neither won a game in the division series.

That was the year – 1996 — the Dodgers stopped being the Dodgers. Lasorda suffered a heart attack in late June and never managed another big-league game. When the season ended, the O’Malley family announced it intended to sell the team. Two years later, the Dodgers were the property of Rupert Murdoch and News Corp., Piazza was a Florida Marlin, and then a New York Met, the cap he wears this weekend in Cooperstown. A longtime Dodgers employee once grumbled over a few beers, “The biggest mistakes this franchise ever made was dumping two catchers named Mike.”

One — Mike Scioscia — became a more than capable manager down the road in Anaheim, in 2000. (Over the same period, the Dodgers have employed six managers.)

The other Mike went to the Hall of Fame.

He will be inducted Sunday, under another franchise’s banner, and the fans of the organization that took him 1,390th in the 1988 draft – out of 1,433 – will mourn the 250 home runs and seven All-Star appearances and millions of hardball moments that belong to someone else. They’ll mourn the decisions of grown men who couldn’t see that a player such as Mike Piazza comes along so rarely, that the pure luck of 1,390 out of 1,433 ought to be bled for a lifetime, that the temporary salve of Gary Sheffield, Charles Johnson, Jim Eisenreich and Bobby Bonilla would never be the equal of one forever Hall of Fame catcher, that the dollars saved that day would come due almost two decades later.

It is a strain to recall Piazza as a Dodger, though he was at his best as a Dodger. The uniform he wears says New York, where he stayed longer. The World Series home runs were in a different blue, under a darker cloud. The signature swings — quick and loose, the bat barrel clanging off his back at the finish, the ball crisp 2-irons in flight — came in a ratty ballpark in steady decay, for fans who hadn’t lived his thunderbolt arrival from a cornfield or wherever the 1,390th pick is summoned from.

Twenty-four years after his debut, 18 since he was traded away, Mike Piazza enters the Hall as a lot of things. As a catcher who could hit with Bench and Carter and Rodriguez and Fisk and Berra and Dickey and Cochrane, the best in history. As a slugger who wears the scars from an era of suspicion. As one of 55 to hit as many as 400 home runs. As a bright light from a day — 9/11 — that scared us all. As a New York Met, just as Tom Seaver, and only Tom Seaver, did before him.

Also, because this is the way an organization loses its bearings and can hardly find its way back, Mike Piazza enters the Hall as all of those things and more, and not as a Los Angeles Dodger.