What North Korea's Latest 450-Mile Missile Test Actually Means

The North Koreans have fired off yet another missile. As is "normal," the world is throwing itself into a tizzy trying to figure out what this means, what might happen next, and various details about the test-launch that might give them new insights-or at least provide them fuel for the next all too brief news cycle. You can safely ignore most of that.

Here is the bottom line: The NORK missile was fired from the northwest corner of the country. It traveled 120 miles up, and it came down somewhere around 450 miles away, in the Sea of Japan off the east coast of North Korea. The only significant new piece of data is that the missile did apparently successfully re-enter the atmosphere (the edge of space being 62 miles up) without tearing itself to shreds. That suggests the North Koreans have developed at least a moderate capability to craft a "reentry vehicle." Without that piece of the pie, any possible ICBM is essentially scrap metal.

Items in some dispute: Did it land roughly 60 miles from Russian territory (as the US claimed), or 180 miles out to sea from Russia, as the Russians claim? And how, if it went straight up, or at a slight angle, did it land 450 miles away? As for the first question, it does not really matter. But the second question is intriguing. Bear with me as I combine my physics-geek side with the historian in me.

First, we need to backtrack to a full 99 years ago, to the closing acts of the First World War. In the Spring of 1918, Imperial Germany and her allies launched a massive offensive on the Western Front. Using new tactics, and troops freed up by the collapse of Imperial Russia, they made larger gains than anyone had since the opening days of the war. It was a desperate last shot, trying to knock the Allies out before the full weight of American forces-then arriving by the tens of thousands per day-could be brought to bear. To do this, the Germans would try just about anything.

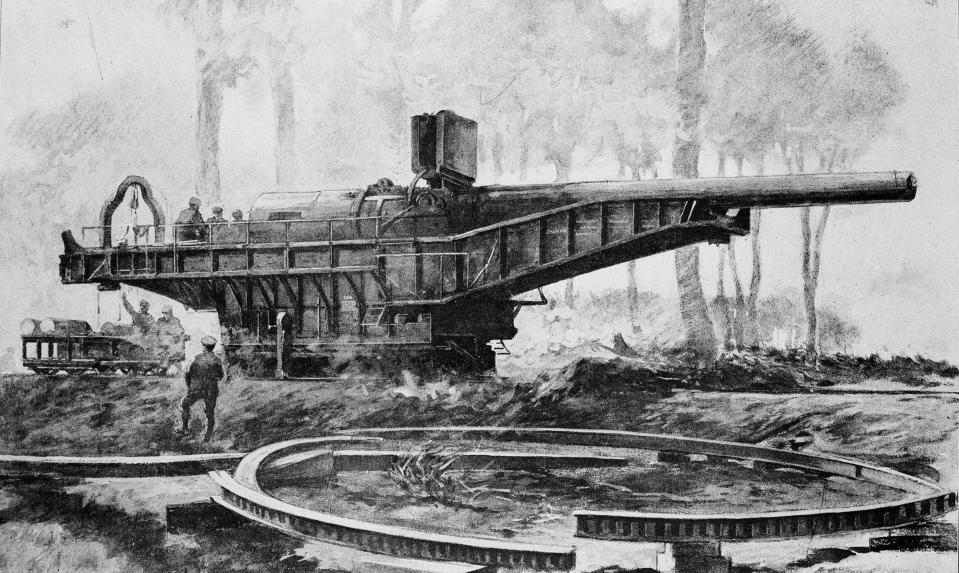

So it was that weapons, or at least munitions, first went into the stratosphere at the height of this offensive. Between March and August 1918, the Imperial German Army unleashed a massive weapon known as the Paris Gun. Somewhat obviously, it was aimed at Paris.

This thing was massive. The barrel of the artillery piece was more than 110 feet long. It was so huge it had to be assembled in place and mounted on a railway car (and custom made tracks) to move it in and out of cover. It fired a shell that weighed about 230 pounds out to a maximum of 81 miles, and downtown Paris was just a bit closer than that at the time. When that shell left the muzzle, it would not touch the earth again for about three minutes, and in that time it would go some 26 miles up. Those last two bits are what reminded me of the parallel.

See, to actually hit a target at that range, it was very helpful that the round actually left the thicker part of the atmosphere and spent some time in the stratosphere. Thinner air = less resistance. But there is another part of that equation. See, the time of flight meant that planet Earth actually rotated a measurable amount between when the shell was fired and when it came down. Since the Germans were firing from northeast to southwest towards Paris, that meant they had to aim their cannon slightly to the east of a true straight line. In other words, they had to aim not where Paris was, but where it would be in three minutes.

All of which more or less explains how it was that the NORKs fired a missile straight up, and it came down 450 miles east. Different news sources place the time-of-flight of the North Korean missile at between 23 minutes and "half an hour." The earth rotates at 1,000 miles an hour. That gives us about the longitudinal distance traveled by the missile between when it went up and when it came down. (Some of the difference may also be attributed to lateral pressure caused by the atmosphere on the way up and the way down, remembering that most of the atmosphere is moving along with the planet as it spins.)

And that, folks, is your geek science-history update for the day.

* Following our own Dear Leader's lead, I am taking Charlie's advice and have now opened a Twitter account. You can follow me, if you are a glutton for punishment, @RobertLBateman.

Robert Bateman is the son of a research physicist and an Art History major. His childhood hero was, literally, Richard Feynman. For him, The Big Bang Theory is not so much light entertainment as it is a documentary. As always he can be reached at R_Bateman_LTC@hotmail.com.

You Might Also Like