How Muhammad Ali’s ugliest fight paved the way for Mayweather-McGregor

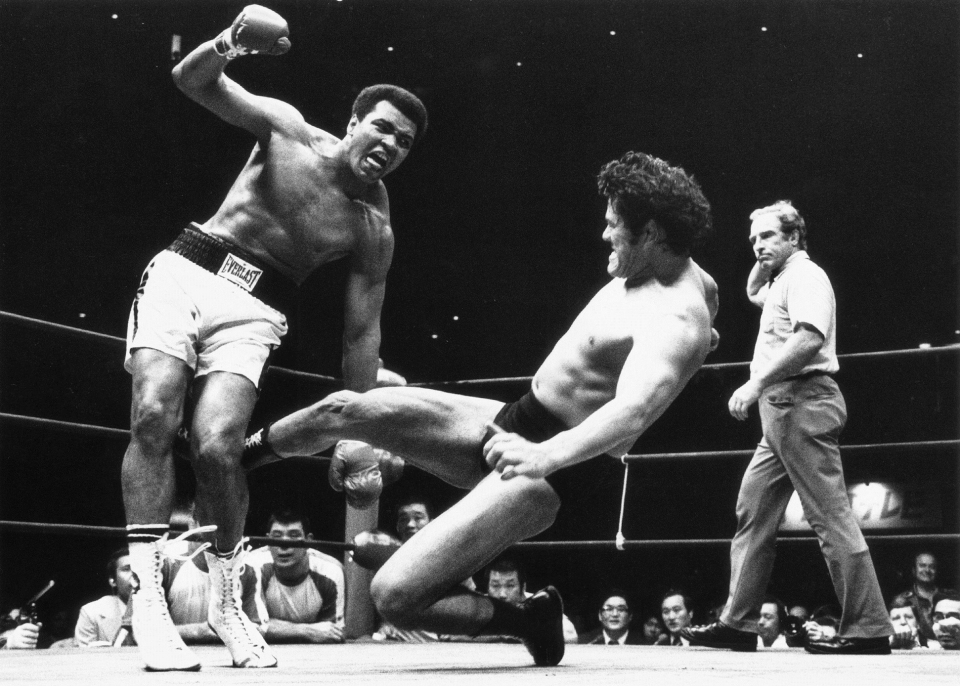

Muhammad Ali hoisted himself up on the top rope of the ring, bellowing over the referee’s head. The Greatest of All Time was fumbling his way through his ugliest fight ever. Below him, on the canvas, his opponent, Japanese wrestler Antonio Inoki, scuttled like a crab … a crab that was delivering kick after vicious kick to Ali’s legs. Ali, incensed, could do no more than yell at the empty air between him. Ali was fighting a completely unfamiliar opponent, and for the first time in the ring, he had absolutely no idea what to do.

When Floyd Mayweather Jr. steps into the ring against MMA legend-in-the-making Conor McGregor on Aug. 26, he won’t be breaking new combat-sports ground. For as long as there’s been boxing, there have been boxing champions who have wanted to challenge masters of other combat disciplines—none more celebrated than The Greatest himself.

Cast your mind back to the summer of 1976, an era when red-white-and-blue patriotism was running nearly as high as gas prices. Ali was at the absolute peak of his celebrity, if not his boxing prowess. He was less than a year removed from the Thrilla in Manila, where he and Joe Frazier literally nearly beat each other to death.

“In the summer of 1976, Muhammad Ali might [have been] the most famous man on the planet. He was clearly the most famous athlete in America,” said Josh Gross, author of the book “Ali vs. Inoki.” “Maybe the Pope was more known than Ali at this stage.”

Around this time, Japanese fight promoters came to Ali’s management team with an intriguing offer: $6.1 million—the equivalent of about $26 million today—to fight Antonio Inoki, one of Japan’s premier wrestlers. Japan would be putting up all the money, and Ali would simply show up and … well, those details would be worked out later.

Wrestling hadn’t yet achieved the headlock on public consciousness it would hold in the 1980s. The World Wrestling Federation was still in its infancy; in those days, wrestlers would still stomp the canvas at the same time as they threw a punch to sell the effect. Ali, a longtime wrestling mark and always a hyper-competitive fighter—plus a guy in need of money—threw himself into the Inoki idea with his typical style: arrogant bravado and challenge-the-planet lip.

Inoki, meanwhile, wasn’t quite as well-known globally as Ali, but in Japan, he’d already achieved legend status inside the ring. “He was The Rock, Hulk Hogan, and Stone Cold Steve Austin wrapped up in one,” Gross said. “Except while those guys were showmen—and I’m not saying they’re not tough guys—but [Inoki] was a genuinely skilled competitor … Inoki was very well versed in real fighting, real submissions. He knew how to tie someone up and strangle them.”

“I couldn’t figure how they were going to do this,” Bob Arum, at that time Ali’s promoter, told Yahoo Sports. “So I went to see Vince McMahon [Sr.], who I’d worked with previously on Evil Knievel Snake River Canyon jump.” The fact that Knievel’s attempt at jumping the Snake River ended in sputtering failure didn’t deter Arum or McMahon, who worked up a scenario for the “fight.”

As McMahon imagined it, Ali would pound on Inoki, who would carry a small razor blade into the ring and slice his own eyebrows. Blood would be everywhere, and Ali would plead with the referee to stop the fight. While Ali had his back to Inoki, the Japanese wrestler would leap on him, pin him, and the fight would be over. Ali would get to his feet and bellow, “This is just like Pearl Harbor!” and cash a fat check, political sensitivity be damned.

“Ali would play the good Samaritan with this guy’s blood pouring down from his face,” Arum said. “He would lose, but he would lose with honor. Ali was fine with that.”

Podcast: How Ali’s worst fight paved the way for Mayweather-McGregor

Subscribe to Grandstanding • iTunes • Stitcher • Soundcloud

To promote the bout, Ali began a series of promotions for the Inoki fight that put him in wrestling hotbeds. On June 1, 1976, Ali “just happened” to be ringside during a Pennsylvania wrestling match that featured the 400-pound Gorilla Monsoon. Ali and Monsoon exchanged words, and then Ali stripped out of his suit coat and shirt to climb into the ring.

It didn’t go well.

Monsoon grabbed Ali, hoisted him onto his shoulders like a toddler, and helicoptered Ali five times before throwing him to the canvas. Ali staggered back to his corner, then rolled out through the ropes, trying to maintain his dignity. It was all a work, a show to give Ali a cameo in the world of professional wrestling. But it ended up being a bad omen, one that everyone ignored.

Monsoon and Ali had practiced the moves backstage, with Monsoon showing Ali how to fall and land directly on his back to minimize the impact. But on his way down, Ali flinched, and landed on his hip. (You’d do at least that much if you’d been thrown from seven feet in the air.) So Ali wasn’t entirely faking when he staggered out of the ring.

“Oh Christ,” said longtime Ali confidant Gene Kilroy, seeing Ali grimace in pain, “we’re gonna ruin this thing.” And by “this thing,” he meant everything from Ali’s next fight to Ali’s career.

Soon afterward, Ali and crew flew over to Japan, and that’s where all the planning went off the rails. Inoki clearly wanted to use this fight as a venue to demonstrate the validity of wrestling as a discipline, not a show, so somewhere along the line, everyone decided that the script was out the window and a real fight was on. The question now: how to set up a fight between two combatants with completely different skill sets?

Negotiations took two weeks, lasting all the way up to the day of the fight. Since this kind of fight had never been held before, no one knew exactly what was, and wasn’t, allowable or desirable. No bites, obviously, and no groin punches. Ali’s people managed to get Inoki’s fabled grappling banned, a key concession that left Inoki griping that he’d been handcuffed.

(With that in mind, it’s worth noting that the Mayweather-McGregor fight is being held entirely on Mayweather’s turf, which is why Floyd is the overwhelming favorite. If McGregor was permitted to take Floyd to the ground, we’d see a whole different odds structure, but dancing to Mayweather’s tune means McGregor is all but doomed before the opening bell even rings.)

While negotiations dragged on, promotional hype spread. The fight was simulcast all over the country, most notably at Shea Stadium. There, 33,000 fans watched an “undercard” wrestler-boxer matchup: Andre the Giant vs. Chuck Wepner, a match where the Giant slung the boxer several rows deep into the seats. That match would become the inspiration for the Hulk Hogan-Rocky brawl in “Rocky III,” and it would be by far the most entertaining battle Shea Stadium would see that night.

Just hours before the fight, Ali’s boxing brain trust nailed down rules they assumed would ensure the most favorable possible outcome for their man. “They didn’t know about checking tape over there,” Kilroy told Yahoo Sports. “We could have put brass knuckles in there and they wouldn’t have known the difference.” (They didn’t put brass knuckles in Ali’s gloves, but they did use the lighter eight-ounce gloves—the same weight Mayweather and McGregor will be using—rather than the standard 10-ounce ones, meaning punches would land harder.)

But ignorance flowed both ways. When setting the rules for the fight, Ali’s team made a crucial mistake: they didn’t outlaw kicks. Ali’s trainer Angelo Dundee left kicking on the table, and Kilroy says he knew that was a mistake from the start.

“Angelo,” he recalls saying, “that was stupid.”

“Well, if [Inoki] goes to kick,” Dundee replied, “Ali will walk over and knock him out.”

It didn’t happen that way. As soon as the match began, Inoki dropped to the mat, flat on his back. There he stayed for the rest of the match, executing a cunning—if not particularly photogenic—strategy. And it came closer than anyone might have realized to working. Inoki’s back-flop, while graceless, kept him out of range of Ali’s punches … but Ali wasn’t out of range of Inoki’s boots.

“Get up, you yellow bastard!” Ali bellowed. “You’re fighting on the ground! You’re like a woman!” (Remember: this was 1976.)

But Inoki just pounded away on Ali’s legs, kicking Ali more than 100 times with wrestling boots. By the end of the fight, Ali’s left leg, his front in his fight stance, had swollen to nearly twice the size of his right. Not only that, a loose grommet loop on Inoki’s boot had cut Ali’s leg, shredding him with tiny slices.

Ali, enraged, began taking chances, thinking he was quick enough to elude Inoki’s reach. He wasn’t. In the sixth round, Ali dove inward, looking to pound Inoki. Instead, Inoki grasped him and wrapped him up in a clutch that could have spelled doom had Ali not thrown a leg over the rope, forcing the referee to separate the two men.

And there it went, on for the rest of the fight, Ali poking and prodding and Inoki scuttling and kicking. “It was cute for the first round,” Arum said, “but then every round was the same s—.”

The “fight,” such as it was, ended in a draw, with the two judges splitting on their verdicts and referee Gene LeBell scoring it an even 71-71. Not a real fight, not a satisfying scripted outcome, not a decisive winner … Ali-Inoki failed on all counts, and fans across the world were livid.

Even now, four decades later, Arum’s voice drips with disgust at the very idea of the fight. “It was a disaster. It was an embarrassment,” Arum said. “It was something not to be remembered fondly.”

The problem, as he saw it, was that the very idea of a fight across disciplines was flawed at its core. Ali and Inoki brought two completely different sets of skills to the ring, meaning showmanship—not competition—was the only option. When that was out, so too was any chance of an interesting spectacle. “There was no [expletive] way you could make it work unless both parties could rehearse,” he said. “You couldn’t do it with any semblance of reality as an actual contest.”

In the hours after the fight, Ali’s legs were so badly mauled that there was concern about him flying. He’d recover enough to fight Ken Norton for the third time later that year, but he was never the same.

“This was the fight where he lost his legs,” Gross says. “He would never knock anyone down for the rest of his career … This was a pivotal moment in his physical demise.” Ali would go on to fight for another five years; he died last year as one of the most important figures of the 20th century.

Ali and Inoki later became friends, and Inoki would attend one of Ali’s weddings. Inoki, for his part, parlayed his wrestling fame into political capital, serving in Japan’s House of Councilors over the course of several decades. He remains active in Japanese politics to this day.

History hasn’t been kind to the Ali-Inoki fight; those that remember it at all write it off as one of Ali’s worst, an Elvis-in-Vegas excess best forgotten. If anything, Ali-Inoki I-and-only might have lit fires under people who should have known better, football players like Too Tall Jones and Mark Gastineau who assumed their athleticism in one sport would translate easily to another.

“People who don’t realize the difference between [combat] sports are delusional,” Arum said. “It’s like taking LeBron James and putting him in a ring with [current heavyweight champion] Anthony Joshua. He’d get killed. Not because he’s not a great athlete, but he has no training at all in boxing.”

On the other hand, Gross contends that the fight, in a strange way, legitimized wrestling as both sport and entertainment, paving the way not only for the exponential growth of the WWF (later WWE), but in another decade, the birth and growth of MMA. The thrill of seeing two fighters with different skill sets didn’t fade, and MMA bouts standardized rules to let every combatant know what could be coming.

“Even in this terrible fight,” Gross said, “the fact that these two styles came together was inspirational enough for a lot of people to say, ‘this is intriguing. I want to know about this.’”

Plus, there’s this fascinating question: what if Inoki had won? What if his kicks had managed to fell Ali like a chopped redwood? What if Ali had dived at Inoki in the middle of the canvas and couldn’t reach the ropes? What if Inoki had carried through on the Japanese promoters’ threats to snap one of Ali’s limbs? What then?

“I think MMA would have burst onto the scene much more quickly than it did,” Gross said. “I think Ali’s public persona would have taken a hit; I think boxing would have taken a hit. It’s one of the reasons why boxing people really despised this contest, because they saw some risk …. [If Inoki had won] I think you would have seen a lot of fighters gravitate more toward mixed-style fighting and away from boxing.”

Which brings us to one notable figure intrigued by the what-if angle: Conor McGregor. He noted after a public early-August workout that he’s spent time studying the Ali-Inoki fight, the same way he’s studied combat across decades. Neither man played the other’s game, McGregor noted, but that sixth round, when Inoki had hold of Ali, gave us a hint of what could have been.

“If that moment in time was let go for five more seconds, 10 seconds,” McGregor said, “Inoki would have wrapped around his neck or his arm or a limb, and the whole face of the combat world would have changed right there and then.”

You can see why that idea might appeal to McGregor. One twist, one miss, and the farce becomes legend.

____

Jay Busbee is a writer for Yahoo Sports and the author of EARNHARDT NATION, on sale now at Amazon or wherever books are sold. Contact him at jay.busbee@yahoo.com or find him on Twitter or on Facebook.

More Mayweather-McGregor coverage from Yahoo Sports:

• A more measured Mayweather regrets gay slur

• Mayweather vows to make McGregor pay for racist remarks

• How 5 years, fate led to Mayweather-McGregor superfight

• How Mayweather-McGregor could be a betting ‘disaster’