The man behind a most improbable Heisman Trophy story

Vince Passas was on his front steps chatting on the phone with a real estate client last January when his wife rushed outside and interrupted the conversation.

“Tua’s going into the game!” Glenda Passas yelled. “Tua’s going into the game!”

“For real?” Vince replied.

“Sorry,” Vince said into his phone, “I’ve got to go.”

Nick Saban left many viewers perplexed when he benched his starting quarterback at halftime of college football’s national title game, but Vince Passas wasn’t one of them. The quarterback guru understood why Saban would entrust Tua Tagovailoa with Alabama’s title hopes because he knew the unproven freshman’s history better than anyone.

Tagovailoa first started showing up to Passas’ weekly quarterback clinics in Honolulu at age 9, never bothering to measure himself against kids his own age. He’d jump in line with the high school quarterbacks during drills and try to outperform them, prompting Passas to playfully taunt them, “Why does a 10-year-old throw it better than you?”

By the time once-skinny Tagovailoa entered high school at the Honolulu private school where Passas coaches, he stood 6-foot-1, 210 pounds with a rocket arm, pinpoint accuracy and the strength and elusiveness to evade would-be tacklers. In 2014, Tagovailoa beat out a returning all-state quarterback to earn the chance to start as a sophomore. Two years later, he led the Saint Louis School to a state championship, shattered a slew of passing records and accepted an invitation to play for college football’s premier program.

[National Signing Day: Sign up for a Rivals subscription, get $99 worth of free team gear]

Having watched Tagovailoa display poise under pressure often during high school, Passas had confidence the quarterback wouldn’t be flustered taking his first meaningful snaps at Alabama on college football’s biggest stage. He wasn’t surprised when Tagovailoa exposed a Georgia defense geared to stop the run, throwing a pair of second-half touchdowns to force overtime. And when Tua uncorked the championship-clinching 41-yard touchdown bomb in overtime, Passas wasn’t shocked by that, either.

“As soon as it left his hand, I knew it was six,” Passas said. “We must have run that play at least 10 to 15 times a day at practice. He could have run it with his eyes closed.”

The quarterback whisperer

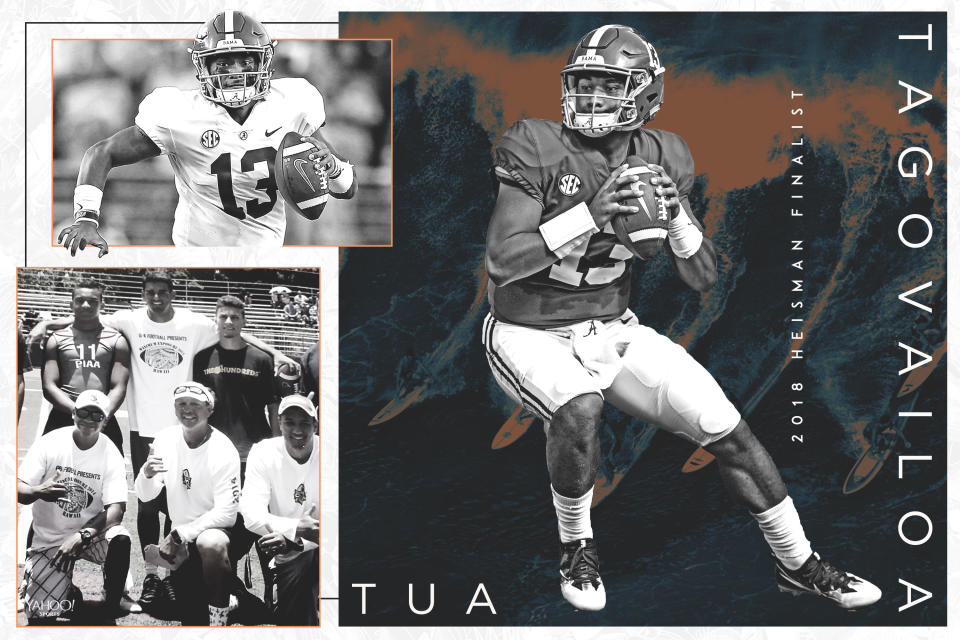

Less than a year after bursting onto the scene with a walk-off touchdown pass for the ages, Tagovailoa is now well known enough to be referred to by just his first name. He’s followed up his breakthrough title game by leading top-ranked Alabama to a 13-0 record this season, raising the possibility that he could become the second Heisman Trophy winning quarterback in four years to train with Passas and hail from the Saint Louis School.

In 2014, Marcus Mariota became Saint Louis School’s first Heisman winner after guiding Oregon to an appearance in the College Football Playoff. Tagovailoa could follow Mariota on Saturday if he secures more votes than fellow Heisman finalists Kyler Murray of Oklahoma and Dwayne Haskins of Ohio State in what is expected to be a very tight race.

Only two high schools have ever produced multiple Heisman winners: Onetime Texas power Woodrow Wilson with Davey O’Brien (1938) and Tim Brown (1987) and Southern California juggernaut Mater Dei with John Huarte (1964) and Matt Leinart (2004). Fork Union Military Academy can also claim a pair of Heisman winners because Vinny Testaverde (1986) and Eddie George (1995) both spent a postgraduate year at the Virginia school.

“There’s no one better than Vinny Passas. Everything I know about quarterback play started with Vinnie.” — Timmy Chang

Saint Louis would be by far the most improbable member of that list given that it’s not located in a state teeming with football prospects, nor does it have a massive student population. The all-boys Catholic school overlooking Waikiki Beach has an enrollment of roughly 800 students from kindergarten to 12th grade.

That Saint Louis could produce two Heisman-winning quarterbacks in four years only adds to the unlikeliness. Hawaii has long churned out imposing linemen because so many players hail from big, thick Samoan and Tongan heritage, but the state had never been known for producing skill position talent until Saint Louis quarterbacks began challenging that stereotype.

On fall Saturdays in 2000, three former Saint Louis quarterbacks started for Division I colleges – Timmy Chang at Hawaii, Darnell Arceneaux at Utah and Jason Gesser at Washington State. Since then, Saint Louis has sent six more quarterbacks to Division I programs and a few others to lower-division colleges, from Mariota and Jeremiah Masoli at Oregon, to Chevan Cordeiro and Jeremy Higgins at Hawaii, to Tagovailoa at Alabama.

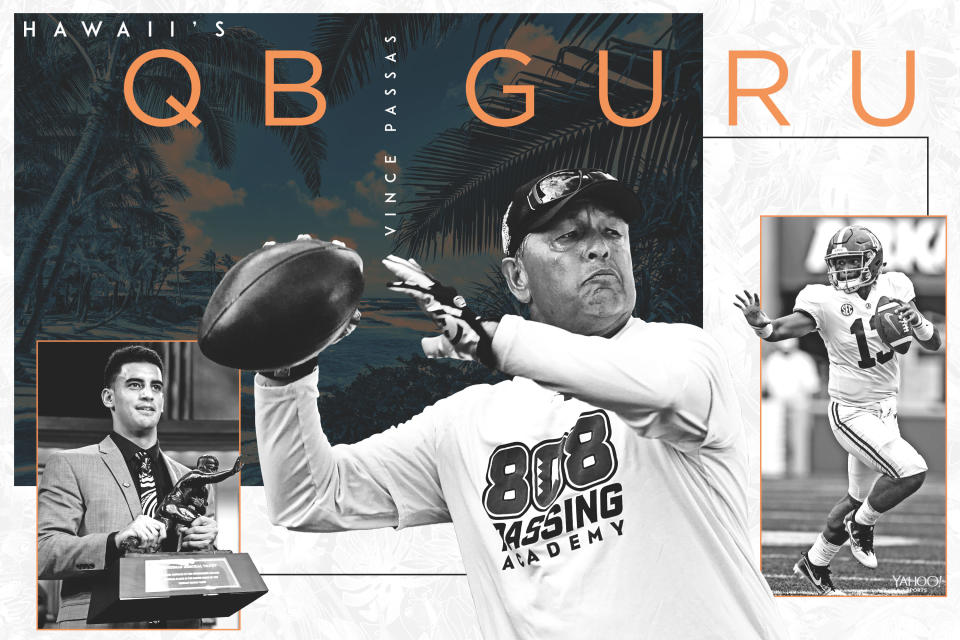

The common thread among the elite passers that Saint Louis has produced is Passas, who has coached the school’s quarterbacks for the past three decades. The quarterback guru coaxes the best out of his pupils with his firm grasp of proper passing mechanics, his emphasis on leading by example on and off the field and his knack for making complex ideas easily digestible for high school kids.

“There’s no one better than Vinny Passas,” said Chang, the former Hawaii standout who still ranks second among Division I quarterbacks in career passing yards. “Everything I know about quarterback play started with Vinny. He’s the best at his craft, and then his heart makes him truly unbelievable.”

Whereas Passas’ sphere of influence was once mostly limited to the Saint Louis School, that has changed drastically over the past 10 to 15 years as Hawaiian kids have shown more interest in playing quarterback.

It started when June Jones installed the run-and-shoot offense at the University of Hawaii and qualified for six bowl games in nine years, from 1999 to 2007, leading some of the state’s many run-first high school programs to adopt a more pass-happy approach. The success of Chang, Mariota and now Tagovailoa also showed young Polynesians that anything’s possible — that Hawaii can produce more than just warriors in the trenches.

Now kids from across Oahu and the outer islands flock to Passas’ camps or seek out private lessons in hopes of one day becoming the next Mariota or Tagovailoa. As a result, Hawaii is producing more fundamentally sound prospects (UCF’s McKenzie Milton is another Passas product) and becoming a state that quarterback-hungry college recruiters can no longer afford to overlook.

“When I came back to Hawaii in ‘99, people were not coming here to look for quarterbacks,” Jones said. “I think that’s changed now after the success we had throwing the ball and the trickle-down effect that caused. Local kids want to learn to play the position and Vinny makes sure they start off with a good understanding of the proper way to throw the ball.”

Vinnyisms

Among the reasons Passas first began coaching quarterbacks was to give promising Hawaiian passers an opportunity to go farther in the sport than he himself did. The self-taught Passas had the talent to play beyond high school but lacked a mentor to help him perfect his mechanics or teach him to read opposing defenses.

Passas guided Saint Louis to a league title as a high school senior in 1973, but a rain-soaked shutout loss in the state of Hawaii’s inaugural Prep Bowl was his final competitive football game. He played baseball in California at the University of La Verne for a couple years before returning to Oahu in 1976 and beginning his coaching career.

When Passas took over as varsity quarterbacks coach at Saint Louis, the Crusaders were one of the only schools in the state running a pass-happy system. Coaches Cal and Ron Lee had learned the run-and-shoot from masters Jones and Mouse Davis, then used the one-back system to torment opposing defenses and spread them too thin.

Fearful that a few weeks of preseason practice wouldn’t be enough time to develop a starter capable of running the Lee brothers’ system, Passas began organizing year-round workouts every Sunday for his varsity quarterbacks. Passas used that time to teach proper throwing mechanics and to demonstrate how to call the right play or make the right read based on what look the opposing defense was presenting.

“I knew nothing about how to read a secondary when I started with him,” said John Hao, one of Passas’ first quarterback pupils at Saint Louis. “In Hawaii, we weren’t taught to look at how many safeties were on top or to identify potential blitzers at a younger age. He pounded it into my mind with continuous repetition. He would train your eyes and drill into your mind what you needed to look for.”

Passas’ ability to attract promising quarterback prospects and unlock their potential helped Saint Louis capture 14 straight state championships from 1986 to 1999, a dynasty unmatched in the history of Hawaiian high school football. Future college standouts Arceneaux (Utah), Gesser (Washington State) and Chang (Hawaii) each quarterbacked the Crusaders to a pair of state titles during that run.

“Comparing Coach Vinny with the camps out on the mainland, he runs one of the best camps in the country.” — Galu Tagovailoa

Saint Louis’ aura of invincibility waned after longtime head coach Cal Lee left to join Jones’ staff at Hawaii in 2001, but Passas’ stabilizing presence ensured the Crusaders still typically had one of the state’s top quarterbacks year after year. Tagovailoa chose to attend high school at Saint Louis largely because of the rapport he had developed with Passas from attending his weekly clinics for years.

Every Sunday, Tagovailoa would make the 25-mile drive from Ewa Beach to Honolulu, measure himself against Mariota and the other older quarterbacks during passing drills and pepper Passas with questions about his footwork and form. Tagovailoa would then return home and work with his father and younger brother to incorporate whatever he learned.

As Tagovailoa grew older and more well known, he participated in prestigious camps in California, Texas and Virginia. There were tidbits he took from each, but his overall takeaway was that none of the more celebrated mainland quarterback gurus offered better instruction than what he got back home.

“Comparing Coach Vinny with the camps out on the mainland, he runs one of the best camps in the country,” said Galu Tagovailoa, Tua’s father. “You’ve got to give Vinny a lot of credit for what he has done. He doesn’t even have a son out there, and he puts in a lot of time with those kids. He’s really good at what he does.”

A key factor in Passas’ effectiveness as an instructor is his voracious appetite for learning.

Each offseason, Passas watches new instructional videos, attends clinics across the country and seeks advice from the likes of Tom Brady’s longtime personal throwing coach or one of the luminaries at the Manning Passing Academy. Passas then returns home brimming with new ideas, from innovative drills to help quarterbacks manipulate the pocket, to cutting-edge run-pass option plays, to fresh ways of explaining familiar concepts.

“You have to evolve with the times and try to stay one step ahead of the competition because everyone is always trying to find new ways to counter what you’re doing,” Passas said. “Once you stop learning, I think it’s time to retire.”

The amount of time Passas devotes to his quarterbacks only increases whenever a new season draws near. Not only does he often throw with them after practices until well after dark, he also studies game film with them to highlight correctable mistakes or to note weaknesses in opposing defenses they can exploit.

“Me and him were like best friends in high school,” said Jeremy Higgins, who started ahead of Mariota for two years at Saint Louis before playing collegiately at Utah State and Hawaii. “I’d call him all the time. We’d always get shaved ice after practice and then just sit together watching film and breaking down defenses. That made our relationship super close.”

Film study and footwork drills can get monotonous after awhile, but Passas uses his dry sense of humor and colorful expressions to keep things light. Quarterbacks who played for him still get a chuckle over some of his trademark catchphrases.

When a quarterback displays more interest in his gear than his game, Passas might tell him, “You can put a mink on a monkey, and it’s still a monkey.” When a quarterback throws a flurry of bad passes during a Sunday workout, Passas might joke, “Cuz, I just went to church, and you’re going to make me swear at you today?”

A pinpoint downfield pass isn’t a merely good throw. It’s “dropping a dime.” The backside of a play against certain defensive looks isn’t just useless. It’s “t-ts on a bull.”

“We call them Vinny-isms because he’s got so many,” said Arceneaux, the former Saint Louis quarterback who now serves as offensive coordinator at Southern California football power Servite High School. “I still use all these quotes. The kids crack up when I say them. They’re like, ‘Where did you get this?’ ”

A deal with God

Passas may have been content to limit his influence to the Saint Louis brotherhood and a select few other quarterbacks were it not for the tragedy he and his family endured. The younger of his two daughters died in 1996 only seven days after her fifth birthday, a nightmare made worse by the suddenness of her passing and the lack of clarity regarding her illness.

One day, she was Passas’ “little angel,” a happy, healthy girl. The next, she began vomiting uncontrollably, her vital organs stopped working and she slipped into a coma.

Doctors couldn’t identify the virus attacking Natasha Passas, nor did they have any way of combating it. As a result, Vince and Glenda made the impossible decision to take their daughter off life support after tests to assess her brain function revealed no positive signs.

“In a matter of hours, poof, she was gone,” Passas said. “That was a really challenging period in my life. I was questioning my faith. I didn’t want to go back to church. I thought about whether to end it all, whether to sink deeper into the abyss.”

What eventually helped Passas recover was a pair of conversations he had at Natasha’s funeral with elderly women he didn’t recognize. Both told him the only way he’d survive this was by helping other people, a message he came to interpret as a sign he needed to rededicate himself to making a difference in the lives of the boys he coached.

“He made a deal with God,” Glenda Passas said. “He said, ‘You take care of my daughter in heaven and I’ll take care of these young men here on earth that want to do this.’ ”

When more and more local kids began showing interest in the quarterback position after Jones’ run at Hawaii and the emergence of Mariota, Passas turned no one away. He opened his weekly passing clinics to quarterbacks and receivers at rival high schools and to aspiring players as young as 5 years old — often free of charge.

“Moms will just drop their kids off with me and use me as free babysitting service,” Passas said with a chuckle. “One day there was a 5-year-old kid who fell down and was crying. I was like, ‘Gosh, where’s your mom?’ He said, ‘She went to go shopping. She told me she was going to come back.’ ”

Having dozens and dozens of participants at every Sunday clinic forced Passas to change his approach.

Instead of teaching each kid individually, Passas now sets up a handful of stations for them to make different throws and positions a volunteer coach at each one while he serves as a roving instructor. The goal is for the quarterbacks to benefit from competition and repetition, from the desire to match or surpass one-another on every throw.

At the end of every clinic, Passas gathers the participants in a circle and urges them to make a positive impact on those around them, whether by crediting their linemen, encouraging a struggling teammate or performing a random act of kindness for a stranger. He’s especially adamant that his quarterbacks thank their moms every day and behave like it’s Mother’s Day 365 days a year. The fastest way for a quarterback to incur Passas’ wrath is not by throwing interceptions but by showing disrespect to their mothers.

“I saw him get very upset with a little boy when he told his mother to shut up,” Glenda Passas said. “He was like, ‘That’s how you talk to your mom? You’ve got to leave and don’t come back.’ ”

‘He just loves being poor’

As Passas’ stature has increased and his camps have mushroomed in size, the price that he charges has remained the same. Participants in Passas’ Sunday clinics sometimes pay nothing and never shell out more than $5 or $10 apiece – just enough to cover the cost of paying for insurance in case of injury.

Passas’ refusal to charge market value often serves as a catalyst for arguments between him and his wife. Glenda Passas doesn’t want her husband to gouge families by charging hundreds of dollars per hour the way some quarterback gurus do, but she wishes he’d stop giving away his services for pennies on the dollar.

“We fight about this all the time,” Glenda said with a laugh. “He just loves being poor. I tell him, ‘You can’t even find a babysitter for $10. I’m not trying to be greedy or anything, but Vincent, you run one of the best quarterback camps in the nation. You’ve got to know what you’re worth.’ ”

Not only does Passas refuse to charge more, he’s actually apologetic about charging families any money at all to work with him. The full-time real estate agent views coaching quarterbacks as a way to give back rather than a way to get rich.

“What I get out of this is to see in someone’s eyes that they’ve gotten better or that their confidence has climbed a couple levels,” Passas said.

If watching his quarterbacks thrive is what makes coaching rewarding for Passas, then Tagovailoa’s ascent to national prominence must be especially satisfying. The strong-armed southpaw has gone from trying to match Mariota throw for throw during passing drills as a kid to trying to follow in his footsteps as a Heisman Trophy winner.

The Heisman ceremony appeared likely to serve as a coronation for Tagovailoa before a rocky performance in Saturday’s SEC title game added some intrigue. Now the voting for college football’s most prestigious individual award looks like a dead heat between Tagovailoa and Murray, with Haskins still in the mix as well.

Passas plans to be at the Downtown Athletic Club on Saturday just like he was for Mariota’s ceremony four years ago. He’ll be excited for Tagovailoa and for the Saint Louis School if the Alabama quarterback wins, but he insists he would take no personal pride in becoming the rare quarterback coach to help groom two Heisman winners.

“I don’t think of it that way,” Passas said. “I’m just so grateful our paths have crossed. I thank the Lord for choosing me to be part of their lives and part of their journeys.”

There’s a chance this won’t be the last Heisman ceremony Passas attends, the way he speaks glowingly about some of the young Hawaiian quarterbacks coming through his pipeline.

Jayden de Laura, the current varsity starter at Saint Louis, already holds a scholarship offer from Hawaii as a junior. A.J. Bianco, a freshman at Saint Louis, reminds Passas of Mariota because of his throwing motion, intelligence and demeanor. Kahi Graham, a seventh grader at Saint Louis, has physical tools that Passas describes as comparable to Tagovailoa at the same age.

For years, Glenda has pestered her husband about retiring so they can move to New York to be near their eldest daughter. Now she has begrudgingly resigned herself to the fact that her husband won’t be ready to give up grooming young quarterbacks anytime soon.

“He used to say he’d retire when Marcus graduates,” Glenda said. “Then he’d say, ‘I can’t leave before Tua. Tua’s my prodigy. I’ve been working with him since he was 8 years old.’ That came and went, and then he said, ‘This is Jayden’s first year. I’ve got to stay.’ ”

Soon it will be Bianco. Then Graham. For Hawaii’s quarterback whisperer, the mission is never done.

– – – – – – –

Jeff Eisenberg is a college basketball writer for Yahoo Sports. Have a tip? Email him at jeisenb@oath.com or follow him on Twitter!