Learning the horrors of our Kentucky history should make us uncomfortable: Opinion

“Every time we start to get ahead

They hate it

They’d rather see us broken

And incarcerated.”

This is the refrain to a spoken word poem created by Black middle and high school students in a creative writing workshop with Hannah Drake. They performed it at the dedication of the (Un)Known Project, a memorial to enslaved people whose stories may never be uncovered.

Against the backdrop of the Ohio River in Louisville, Kentucky, where enslaved people once stood and imagined freedom on the other side, the children chanted the chorus over and over as each individually came forward with their own verse detailing racial injustice, police violence, poverty and cultural appropriation. It was shattering to hear them tell what we wish weren’t the truth in the 21st Century: racism is alive and well all around them. They see it. They know it personally.

The dedication was attended by many Black people, along with white allies who also had marched alongside their Black sisters and brothers, demanding justice when George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery were killed. These allies took classes, made donations, listened with vulnerability to uncomfortable stories of racist systems and events, and they began to challenge racist power structures in the workplace, academics, etc.

Around the same time, The New York Times published “The 1619 Project,” which makes a clear and irrefutable argument that racism is not anecdotal, practiced by a few bad people, but built into our systems which were created when our country was steeped in (and getting powerful and rich from) slavery.

This new white concern did not go unnoticed. As the Urban League publicly stated later, “For a moment, it seemed that we were ready to wrestle with at least some of the systems perpetrating disparity at every turn.” Like maybe Black people were starting to get traction, to get ahead.

And the kids were right: “They hate it.”

“They” being those steeped in white supremacy who make up a larger percentage of the population than many of us knew. They came back like a steamroller with new voter suppression laws and hysterical “anti-CRT” laws in a desperate attempt to push things back to the way they were. They don’t want Black people voting in large numbers for candidates with their interests at heart. And they don’t want to hear the horrific truth about long-term, unending racial injury that started with kidnapping and enslaving Africans and hasn’t ended yet.

“They hate it.” They don’t want to acknowledge the depth of depravity that created enormous wealth and power that we as whites still benefit from. They don’t want to know the harm that’s been done. They’re afraid of how it will make their children feel to hear those stories. Afraid they’ll be uncomfortable.

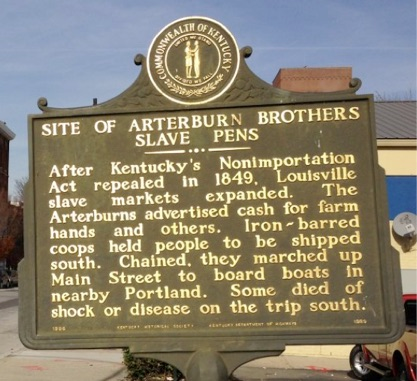

What stories? Well, here’s one set right in our fair city of Louisville. From many accounts, the term we often use for betrayal, “sold down the river,” was invented here, on those same Ohio River banks where enslaved people once looked longingly across to Indiana and freedom. They were held in chains, many even kept in pens. Yes, you read that right. Pens. For human beings. Those pens held people who’d been sold and were awaiting boats that would wrench them away from home, from loved ones whom they’d never see again, to work on plantations in the deep south, where the conditions were known to be much harsher and treatment of slaves much more brutal. It was deeply dreaded: the greatest betrayal. And thus, the phrase came to be: “He (she) was sold down the river.”

Does that story make people uncomfortable? We certainly hope so! We hope it moves us to work for something better. To listen–and try to right the horrific wrongs of the past.

But for now, Black people are being betrayed again–by white parents screaming at school board meetings and by white politicians rushing through voter- and history- suppressing laws. And, by those who sit by silently as it happens. Once again: sold down the river.

What do we plan to do about it?

Deborah LaPorte is Co-Chair (with Di Kerrigan) of listenlearnact.org

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Learning horrors of our Kentucky history should make us uncomfortable