KS farmers worried rock quarries will damage water. So they banded together to fight back

After a rainstorm soaked the Flint Hills one summer day last year, a Kansas farmer crawled down a hill near a creek.

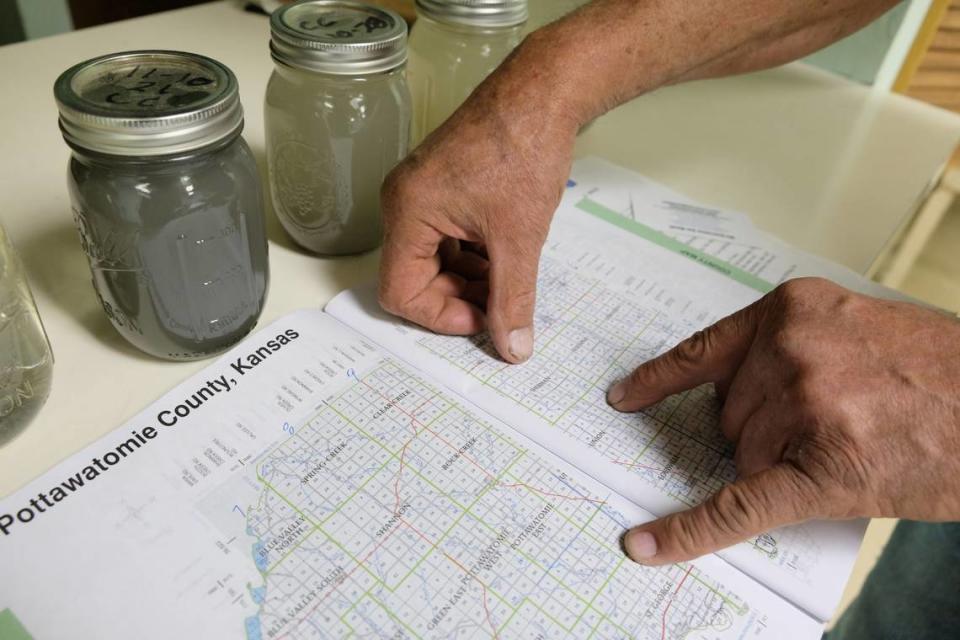

Among the tall grass where snakes hide out, he lowered a mason jar into the water, catching the opaque runoff, and screwed the top on.

He put the container on ice as he had been instructed and drove it about 30 miles south to Kansas State University for testing.

Rodney Biesenthal said he was “hell-bent” on collecting evidence to prove that a rock quarry company was polluting water in Pottawatomie County.

For many years, the company Hamm had operated the mine.

Landowners in the area had accepted what comes along with the quarries: noise from blasting, dust and traffic. But some had begun to notice discolored runoff after it rained, a repercussion that made them worry about the water their cattle and wildlife were drinking.

In summer 2021, Hamm started the process of getting a second quarry approved by the county. It was a tipping point for Biesenthal and many of his neighbors. They began holding meetings, sending postcards and knocking on doors.

“We knew this thing was not going to go away,” he said. “I just went about quietly collecting every time there was a runoff rain, back to the same locations.”

When another company, Mid-States Materials, submitted a permit for a second new quarry, the group of farmers banding together grew.

About a dozen residents voiced their concerns during an Oct. 23 interview at the community center in Wheaton, a town of about 100 people situated 150 miles northwest of Kansas City, where the group often convenes. “Landowners have the right to enter an agreement with a rock quarry, but we also have the right to protect our property that adjoins,” said Lawrence Ubel. “You’re going to diminish the spring water,” said Travis Ross. “We just don’t want the dust and the traffic,” said Wanda Magnett.

The group wants to see the county tighten its permitting rules and the state change its quarry regulations.

The quarry dispute has changed the way Biesenthal sees things. He thought less government was better.

“It probably could be, should be that way,” he said.

“And now as much as I hate to say it, I can’t see anything other than more government intervention keeping people like this in check. It goes against everything I’ve believed for all my life.”

While many of the farmers do not consider themselves environmentalists, they have found common ground with organizations like Audubon of Kansas, which have expressed concern about water, prairie preservation and wildlife including prairie chickens.

Zack Pistora, a lobbyist for the Kansas Sierra Club, visited one of the proposed quarry sites and spoke before the county’s planning and zoning board in April. Pistora referenced Bob Dole’s prediction that heaven looked like Kansas — meaning the state’s “beautiful grassland landscapes, not a rock quarry.”

“It’s a shame that industrial entities are looking at undisturbed, incredible wildlife habitat and grassland ecosystems without the buy-in of the neighbors and the community to basically blast it, blow it up and extract it for its raw resources,” Pistora told The Star.

Others support the quarries as they contribute to economic development, and supply the county and other parts of Kansas with rock needed for construction projects and gravel roads.

“Anytime you need any type of construction from residential to commercial, you just have to have aggregate (rock), there’s no way around it,” said Rich Eckert, an attorney for Mid-States Materials.

Dennis Schwant said his land is an “ideal location” for one of the quarries and that the many neighbors who oppose the development have an “imaginary fear of the unknown.”

The fate of both the quarry permits has wound up in court. The county commission in August denied the Hamm permit, but the company filed an appeal. MSM’s permit was granted in July over the recommendations of the county planning board. The group of farmers filed an appeal in August.

Litigation continues in Pottawatomie County District Court.

Hamm quarry

On the west side of Fremont Road in Pottawatomie County, golden grass murmurs as a gust of wind rushes across the prairie. Then the bucolic scene is interrupted by mounds of gray rock rising from the ground towards the sky. A small sign marks the area: Hamm Quarry, Inc. Inside the fenced area, mountains of crushed limestone dot the landscape along with equipment and a scale house.

Across the street, tractors move soil across a wide swath of bare land. Part of the quarry is undergoing a process known as “reclamation.” Under a 1994 Kansas law, after a quarry is depleted, the soil has to be replaced and seeded.

Biesenthal’s family has had land in Pottawatomie County dating back to 1867. He and other family members farm more than 1,000 acres. One tract of land is about five miles downstream from the Hamm quarry.

In the past 16 months, he has amassed a box of more than a dozen mason jars which he has lugged to public meetings. Their contents range from clear to slightly brown with sediment settled in the bottom to a dark muddy charcoal color, depending on when and where the samples were collected. Some of the samples showed elevated levels of iron, magnesium and limestone, which could be detrimental to both livestock and wildlife, according to results from K-State’s lab.

A rock quarry permit is a “license to contaminate,” Biesenthal said.

He repeatedly tried to get the company, the county or the Kansas Department of Health and Environment to take action on the dirty runoff, a feat that became increasingly frustrating. He felt like he was dismissed as a “plain Jane farmer.”

“I’m just so frustrated at how the system worked — or didn’t work might be more correct,” he said.

Finally on May 25, the Kansas Department of Health and Environment came out for an inspection. Biesenthal called it “a miracle” that there had just been rain.

Tom Stiles, director of the bureau of water for KDHE, said the timing helped the inspector see what was happening at Coal Creek.

“It helped us identify areas that didn’t have practices in place that would keep sediment on site and was actually allowing it to go into the creek,” Stiles said.

In a letter issued to Hamm, KDHE noted “stream discoloration” and said the company’s permit would be reworked to address the problem. Stiles said the company fixed the problem.

“We’re viewing that as an overall success story,” he said.

While Biesenthal may not characterize it in quite the same terms, he said he felt vindicated.

Though the group of farmers has gained the support of environmentalists in Kansas, Biesenthal shies away from being labeled one himself.

“While none of us maybe want to be considered true environmentalists, we sure do not want to be contributing to the downfall of our water quality,” Biesenthal said.

He’s joked with the Sierra Club’s Pistora about how he never imagined they would be “on the same side of the coin.”

“But that’s where we’re at,” he said, noting that farmers and environmentalists have common interests in taking care of land and water.

In March, Hamm applied for a conditional use permit for a new 350 acre quarry that borders nine properties, including land in Biesenthal’s family and through two tributaries.

His presentations with the samples at public meetings — as well as drone shots and a small selection of the 518 “photos associated with quarries” he has accumulated — have irked Hamm. In a letter to county commissioners dated Aug. 4, the law firm hired by the quarry company called Biesenthal’s testimony “a recurring distraction.” The letter left him disgusted.

On Aug. 22, the commission denied the Hamm permit.

Resolution 2022-59 stated the planning board recommended denying the permit because it “would detrimentally effect nearby property.” The county commission concluded that it was not compatible with the character of the surrounding area and did not conform with the county’s Comprehensive Plan. That plan was adopted in August 2019 and notes that “Pottawatomie County has some of the most pristine remaining prairie land in the area.”

Hamm filed an appeal in late September in Pottawatomie County District Court. The case is pending.

The company did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

MSM quarry

Less than five miles from the proposed Hamm quarry, Mid-States Materials (MSM) submitted a permit for a quarry over 320 acres. Some of that area includes rock — mined in 40 acre chunks — while other parts would be used for quarry operations including rock crushing equipment and sediment ponds. The site includes part of Rock Creek, an important water source for the county.

In the eyes of many residents, it was one quarry too many. The group of farmers rallied as many as 80 people together at planning and zoning meetings.

In public comments, residents listed off a litany of reasons they opposed the project: “The area will be scarred forever.” “The land is our heritage and we’re proud of that heritage. The land is to be passed on to our children.” “If you destroy this sod, you (are) releasing tons of carbon per acre into the atmosphere.”

They were encouraged when the planning board recommended to the county commission that MSM’s permit be denied. But the county commission approved the permit on July 11.

James Pierson’s land adjoins the proposed MSM quarry. The property has been in his family since his great-great grandfather arrived in the area.

The environment is his primary concern.

“There is not enough rules and regulations for a rock quarry in this county right now,” he said.

Several of the farmers noted that other counties have more stringent regulations. Wabaunsee County has a list of 31 rules including restricting permits to 80 acres, regular inspections and a prohibition on blasting.

Pierson would like to see the county limit the area that can be quarried at one time, hydraulic studies and “full reclamation.” He has worked on mine reclamation projects before.

“I’ve reclaimed rock quarries and what I did in Colorado is nothing compared to what they do here,” he said. “Here they just throw a handful of grass seed on the ground.”

Pierson said he could be considered an environmentalist in the sense that he’s “more concerned about the environment than money.”

“This land that’s mine, it’s been in the family since the 1870s ... it’s historic to me, but other people just see money.”

Jackie Augustine, executive director of the Audubon of Kansas, testified at one of the county’s planning and zoning meetings. Less than 5% of North America’s tall grass prairie still exists. Even with reclamation, she said, the land will never be the same. A quarry changes the structure of the land, disrupting the soil and its microbes, and the symbiotic relationship between fungi, bacteria, plants and animals.

She’s also concerned about greater prairie chickens in the Flint Hills. The species has suffered a 30% decline since 2015 in the state, according to the Audubon of Kansas.

“It is critical that we conserve habitat now to prevent further declines,” she said in a letter to the commissioners voicing her opposition to the quarry.

Travis and Carrie Ross also have land adjacent to the proposed site. They have seen the runoff from the current Hamm operation.

“We don’t want that to happen to us,” Travis Ross said, adding that degrading the water is a “bad deal,” especially given that most of Kansas is suffering from moderate to exceptional drought conditions.

He believes the county should limit the number of rock quarries.

Pierson has filed an appeal against the county commissioners. In the legal action, he cites a procedural rule saying the commission by law was supposed to refer its quarry permit decision back to the planning board.

Quarry regulations

As the case makes its way through court, MSM has been in the process of getting state permits for the quarry.

KDHE has issued permits for 148 quarries across the state, Stiles, the agency’s water bureau director, said last month.

Companies must get a wastewater permit. They are required to sample wastewater quarterly and complete a compliance evaluation annually. The issue becomes protecting downstream water after storms. But that is not much of a problem, according to Stiles.

“Of all the things that are confronting our aquatic environment across the state, quarries just don’t rise up to a major concern for us,” he said.

Sampling of stormwater discharges is left up to the facility, Stiles said. Companies have to follow general water quality standards, like preventing objectionable odors or floating debris. But no specific rules govern how much rain has to fall to take a sample, how long companies have to collect those samples or what those samples can contain.

KDHE inspects quarries once every five years, unless complaints are made.

“Aggregate (rock) business is a big deal here in the state,” Stiles said. “So quarries are part of our landscape. We’ve got the geology that has blessed us with being able to provide us with some of that aggregate material.”

Eckert, MSM’s attorney, said one of the main reasons the location was chosen was because there were only a few residences nearby.

“Although we had significant opposition from area land owners, the county commissioners took the long view of hey, if we’re going to continue this growth, we need infrastructure and we need rock and that’s ultimately what drove their decision,” he said.

The company has 25 quarries in operation across Kansas, Missouri and Oklahoma. They take several steps to protect the environment, according to Eckert, including using sediment ponds to separate out particles from water. Water samples are taken monthly and after major rains.

In terms of the impact on wildlife, Eckert said animals adjust. Game cameras set up by MSM show animals walk up to quarry equipment.

“The deer, fox, possums, you name it. None of it gets scared off. On some of our quarries, they run cattle ... we’re blasting next to them, or conducting all the operations. They get used to it really, really quickly, and we haven’t seen any adverse impacts on the wildlife.”

He noted that many sites with prairie land are already being used for agricultural purposes.

“It’s not quite fair to say we’re moving into virgin territory because cows have been on there for decades and that’s the case here.”

Landowner Dennis Schwant agreed to lease out his property for the quarry. The 85-year-old rancher said the county needs the rock for things like gravel roads and believes his neighbors are “up in arms for no reason, in my opinion, it’s not really going to affect them.”

“Unless we have an act of God event, there won’t be any runoff,” he said.

County Commissioner Dee McKee voted in favor of both quarry permits. She said the two new quarries would have more regulations than the current Hamm site and that she supports the decisions of the landowners.

“It’s just whoever owns the property has the, I think, freedom to develop it as they see appropriate,” she said.

Commissioner Pat Weixelman voted in favor of Hamm’s conditional use permit and against MSM’s application. He said there are many factors to consider including whether the quarry is near streams or creeks.

“That kind of poses a problem,” he said.

“There are a lot of things that can be detrimental to it going in or it not going in.”

Commissioner Greg Riat voted down the permits. He did not respond to requests for comment.

In November, Pottawatomie County voters approved expanding the commission to five people, which will impact how future decisions will be made.

As far as the two court cases go, the companies, county and landowners will likely have to wait several months for decisions in both cases.

MSM’s permit will be taken up in court for oral arguments Feb. 8. A court date for the Hamm permit has not been set.

Pierson said he’s optimistic about the appeal on MSM’s permit. Biesenthal is not as hopeful about the court cases. But they both believe some kind of change needs to happen.

Biesenthal said at the very least, he wants the Kansas Legislature to implement measures to improve KDHE’s inspection and complaint process.

“My goal in the latter years of my life is to take care of the land in the best of all possibility,” he said.

“That’s my whole goal, take care of things, make it better for the future.”