Spurs set sail with Admiral aboard

The assignment was standard fare for a high school sophomore government class: Write a letter to your state representative about an issue that stokes your political passions.

Some students lobbied opposite sides of the abortion debate. Others wanted the drinking age lowered, or the freedom to buy Guns N Roses’ “Appetite for Destruction” without their parents’ permission.

I wanted David Robinson.

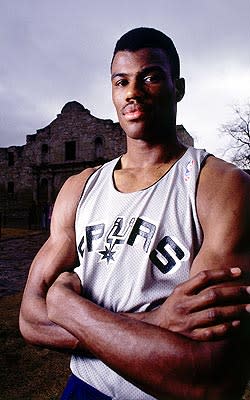

David Robinson helped take the Spurs from 21 wins to 56 in his first season.

(NBAE/ Getty)

As a young NBA fan in San Antonio, already scarred by the trade of George Gervin, these were the darkest of days. The Spurs were coming off a 28-win season that, at the time, qualified as the franchise’s worst. Walter Berry would soon run down a Red Lion hallway chasing Alvin Robertson with a butter knife. I didn’t need another two years of David Greenwood. I needed a savior.

So I wrote my state rep, and suggested he petition the Navy to commute Mr. Robinson’s service commitment. Anyone who had watched those dreadful Spurs teams would understand this was clearly a matter of civic duty.

David Robinson, former Spurs owner Angelo Drossos announced at the time, “is more important to San Antonio than the Pope.”

Twenty-two years later, Robinson goes into the Hall of Fame alongside the game’s greatest player. Robinson wasn’t Michael Jordan, but he meant as much to the city of San Antonio as Jordan did to Chicago. He saved San Antonio’s only major pro sports franchise from relocation. He gave the city an identity, then some much-needed self-esteem. He helped win two championships, but also built a private school with an enrollment made up primarily of underprivileged children. After his playing days ended, he started ministering at a local church.

The Pope? He also delivered a memorable sermon or two in San Antonio. But he didn’t dunk.

History has a way of forgetting that David Robinson could have passed on San Antonio. Drafting him was a no-brainer. Signing him was the challenge. Because Robinson was obligated to spend two years in the Navy, he could refuse to sign with the Spurs then become a free agent when his commitment ended before the 1989-90 season. The Los Angeles Lakers would be waiting with big-city money. With Kareem Abdul-Jabbar retiring, they also would have an opening for a franchise center.

Robinson, however, didn’t wait on L.A. A trip to San Antonio after the 1987 draft helped convince him to make South Texas his next home. So did his own logic: After all, hadn’t the Spurs drafted him? It just wouldn’t seem fair to not show them any loyalty.

This would become a popular theme with Robinson. The same sense of duty that made him such a noble figure, such a perfect fit for an old military town, also likely kept him from becoming an even greater player. Robinson was never ruthless. He was responsible.

The Spurs couldn’t say the same of some of the teammates who surrounded Robinson in the early ’90s. Willie Anderson. Rod Strickland. David Wingate. J.R. Reid. Dwayne Schintzius. Some stayed out too late. Others were lazy. Some just couldn’t play. Robinson didn’t publicly complain about any. Other franchise stars would have wisely demanded better talent. Robinson played with the hand he was dealt, and played well enough to become one of the game’s dominant players.

The league had never seen anyone like him during those early years. He stood 7-foot-1 with a body built like a wasp: narrow waist, broad shoulders, muscles rippling on top of muscles. He protected the rim as well as anyone in the league, but also ran the floor like a guard. He’d track down a rebound 18 feet from the basket, spin on his heels and sprint back for a devastating dunk. John Lucas(notes) once canceled practice after watching Robinson walk halfway across the court on his hands. By the final season of his career, Robinson was still wearing size 30 jeans. Even now, he looks like he could go for 18 and 10.

Tim Duncan, left, and David Robinson teamed to win two championships.

( Getty)

Long before fantasy sports made stat-watching a billion-dollar industry, Robinson filled up the box scores. His numbers have continued to hold up against time. Basketball blog The Painted Area recently did a post that ranked Robinson’s career Player Efficiency Rating of 26.18 as fourth all-time. IBM devised a different statistical formula to rate the NBA’s best player each season, and Robinson won the award five times.

Of course, Robinson was also the only player who didn’t need an IBM to do the formula’s math. Say this much for the Admiral: Basketball never defined him. He took college computer classes at age 14. He played the piano and saxophone. He caddied for Corey Pavin. After the first game of his career, he correctly used “impunity” in a sentence. Years later, Robinson admitted he had learned the word from a Hulk comic book.

Through it all, Robinson stayed true to his family, his faith and San Antonio. Later in his career, it wasn’t unusual to see one of Robinson’s three sons accompanying him on road trips. He and his wife, Valerie, poured their money and time into building the Carver Academy, a private school whose enrollment is now almost completely scholarship-based.

“Sometimes I feel bad for David,” former teammate Danny Ferry once said. “It’s hard having to be perfect.”

Robinson wasn’t perfect, nor did he portray himself that way. His inability to lift the Spurs to the NBA Finals clung to him until Tim Duncan(notes) arrived. Even some Spurs fans pointed to his varied interests as reason for his failures. Jordan nicknamed Robinson “The Negotiator” during the 1992 Olympics because Robinson always had a question or a plan or something.

The role for which Robinson will always be remembered outside of San Antonio is that of Hakeem Olajuwon’s foil in the ’95 West finals. Another lasting image from that series that few people ever saw: Dressed in a suit, water splashing at him, Robinson waded into the Rockets’ shower to congratulate Olajuwon after the final loss. He was a beaten man, and big enough to admit it.

Duncan’s arrival changed everything, of course, and even that was born from Robinson’s commitment. Slowed by a hernia during the 1996 Olympics, Robinson pushed the mass back into his abdomen long enough to lead the United States in scoring during the gold medal game. Back problems followed soon after. Robinson missed the start of the season, returned for six games, then broke his foot. The lost season allowed the Spurs to win the right to draft Duncan.

After shouldering the burden of carrying the Spurs alone for so many years, Robinson welcomed the help. Duncan became the team’s go-to guy while Robinson anchored the defense and rebounding.

“I've never been a Michael Jordan type of player,” Robinson said. “That's not my game. So I guess in some ways Tim kind of let me find my own place.”

Robinson returned the favor. When Duncan was close to leaving the Spurs for Orlando in the summer of 2000, Robinson flew in from Hawaii and helped talk him into staying. Robinson took his turn at free agency the following year. The Spurs made an initial lowball offer to buy themselves some time to gauge Chris Webber’s(notes) interest, wounding Robinson’s feelings in the process.

“This is the first time in my career I thought I wouldn't finish as a San Antonio Spur,” he said.

The following day, angry callers overloaded the Spurs’ phone system. “Get the deal done,” Spurs chairman Peter Holt ordered his front-office staff. “We’re not losing David – and half our fans.”

I never heard back from my state rep. No postcard. No form letter. Out of the 20-odd students in my sophomore government class, I was the only one whose letter failed to generate any response.

I lived. It took two more long years, but David Robinson eventually arrived. For the Spurs – for San Antonio – he was worth the wait.