Imagine what he could do with 10 fingers

LONG BEACH, Calif. — Immediately after she gave birth to her younger son, Casey Dowling realized something was wrong.

First, the room fell silent. Then, doctors whisked her newborn baby away without even letting her hold him.

The most pressing issue was that Dowling’s son was not breathing properly and needed his airways reopened. Of secondary concern was a different sort of problem, a rare abnormality that had gone undetected on the ultrasound exams Dowling took during her pregnancy.

Elijah Alexander McGee was born without a fully formed left hand after the appendage became entangled in his mother’s amniotic bands inside the womb, restricting blood flow and stunting growth. McGee’s rigid left thumb lacked normal flexibility. The other four fingers on his left hand were just stubs.

When doctors finally returned McGee to Dowling a few hours after she gave birth, she initially struggled to summon the courage to peel back the blanket wrapped around him and take stock of his misshapen left hand. Dowling’s first glimpse was a poignant moment, one that unleashed a flood of tears and emotions.

“His whole life flashed before my eyes,” Dowling said. “I thought, ‘How’s he going to live? Are the other kids going to make fun of him? Will he ever get married and have children?’ I think I cried for at least seven whole days worrying about the things he wouldn’t be able to do.”

Dowling had already endured plenty of hardship throughout her life, from battling sporadic medical problems, to being abandoned by her birth parents, to growing up with a foster family she despised. The U.S. Navy servicewoman desperately wanted to provide her kids a more comfortable, less tumultuous childhood than she had, but she feared her younger son’s disability would complicate that mission.

Soon after arriving home from the hospital, Dowling steeled herself for the long journey ahead and made her son a promise. No more tears. No more pity.

“I made a point that that was going to be the last time I took time away from raising him to feel sorry for him,” she said.

And so began McGee’s evolution into one of high school basketball’s most inspirational stories, a player who won’t let his disability limit his ambitions.

*****

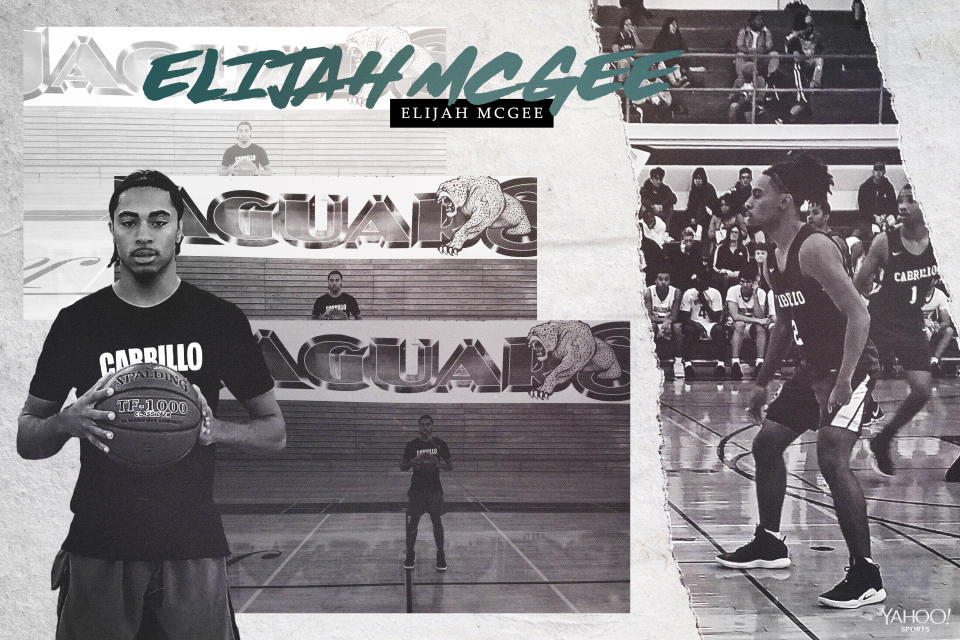

Inspired by his mother’s tough love and strong will, McGee has flourished in a sport seemingly ill-suited to someone with one hand. Not only is McGee the leading scorer on his high school’s varsity basketball team this season, the 6-foot-2 guard also hopes to earn the chance to play in college somewhere next year.

McGee is averaging just over 15.7 points and 8.3 rebounds per game this season for Cabrillo High School in Long Beach, California. He’s also his team’s most versatile defender, a quick-footed ball hawk who chokes off the passing lanes at the top of the Jaguars’ aggressive full-court press.

“He’s a complete player,” first-year Cabrillo coach Kyles Hawkins said. “When he goes off in practice, I always tell our other guys, ‘You’re lucky he doesn’t have all 10 fingers. Imagine what he’d be doing then.'”

About the only thing the 17-year-old McGee has not been able to accomplish this season is transforming long-downtrodden Cabrillo into a winner. Cabrillo seldom attracts enough top players to compete with neighboring powerhouse Long Beach Poly or other tradition-rich programs in its area, but McGee has at least helped the Jaguars win three of their first nine league games and build second-half leads in two others.

Watch McGee play against even the best teams on Cabrillo’s schedule, and it’s often easy to forget about his disability. The slashing guard attacks off the dribble smoothly with either hand, crosses over effortlessly and never shies away from contact around the rim, often making opposing defenders pay for overplaying his right hand and trying to force him to go left.

When McGee blows past his man or buries a series of pull-up jumpers, it sometimes inspires a combination of frustration and disbelief from his opponents. It’s not uncommon to hear opposing players scream, “Take him left! Take him left! He doesn’t have a left hand!” Or to hear opposing coaches yell, “He only has one hand and you’ve got two. Why’s he putting up more points than you?”

“Coaches will sometimes call timeout to try to use his disability to motivate their teams,” said Seti Lam Sam, McGee’s coach with the Long Beach-based Frontline travel ball team. “They don’t understand that this kid really puts a lot into his game to be where he’s at right now.”

*****McGee’s unwillingness to let his disability hold him back is a testament to the influence of his biggest role model. In addition to insisting McGee not use his hand as an excuse for why he can’t achieve something, Dowling also has led by an example by displaying courage while battling her own medical issues.

Though doctors only formally diagnosed Dowling with lupus five years ago, she has coped with symptoms of the chronic autoimmune disease for much of her life. She has endured everything from muscle and joint pain, to hair loss, to face rashes, to difficulty breathing, the flare-ups often waylaying her to the point that simple household chores become a struggle.

Dowling intended to support herself and two sons by serving in the Navy until she qualified for her 20-year pension, but lingering joint pain and swelling forced her to seek early medical discharge.

At first, she found other less physically demanding jobs, sometimes working 12-16 hours in a single day to keep her family afloat. More recently, symptoms from Dowling’s lupus and rheumatoid arthritis have been so crippling that she hasn’t been able to work full time and she has been hospitalized a couple times a year.

“When he showed me, I was in shock. I told my wife and my sons, ‘Look, there’s a kid out there with one hand dominating the game.’” — Seti Lam Sam

No matter how debilitating her condition gets or how tight her budget is, Dowling always puts her sons first.

She sometimes skips a meal or goes an extra few months without new clothes to make sure her boys are well fed or have new basketball shoes. She also often checks herself out of the hospital against the recommendation of doctors because she doesn’t want to miss one of her sons’ marching band performances or basketball games.

“Because I’m the only parent they have, I feel that telling them I can’t make it because I’m sick, that wasn’t an answer I could give them,” Dowling said. “I had to suck it up and go anyway.

“I didn’t get a good adoptive family, so I’ve basically been on my own my entire life. I’ve had to depend on only myself. I don’t have a mom I can call for money. I don’t have an aunt, a cousin, a sister, a brother. There’s literally nobody but me. So if I can’t provide for my kids, who’s going to do that? I don’t have a backup option. I am plan A, B, C, D, E.”

*****Watching his mom persevere through adversity instead of allowing it to defeat her rubbed off on McGee at an early age. He lived by the mantra she instilled in him – that “10 fingers are overrated.”

When McGee’s occupational therapist urged him to use a prosthetic hand or another apparatus to compensate for his disability as a boy, he inevitably turned them down. McGee preferred to adapt on his own, even if that meant holding his toothbrush with his left wrist or all too often dropping plates or glasses while washing the dishes.

He swung on the monkey bars at school as a 5-year-old … and knocked all his front teeth out when his left wrist slipped and his face crashed into a bar. He climbed a tree near his family’s housing complex that same year … and scraped up his back when he fell out.

“I felt like a bad parent when I let him climb that tree, but I also didn’t want my fear to be his fear,” Dowling said. “He was back on the tree as soon as I could finish cleaning him up.”

Schoolyard bullying was inescapable for McGee as a kid due to his disability, and he admits for awhile the taunts and jeers stung. He’d often retaliate with a barrage of harsh words or punches. Then he’d come home in tears and ask his mom why he wasn’t like everyone else.

Often fighting back tears herself, Dowling would tell her son that God didn’t make everyone with blonde hair or brown eyes either, so why should only having one hand be any different? Then she’d remind McGee that just because someone at school said he was weird doesn’t make that true.

It took awhile for Dowling’s advice to resonate with her son, but by middle school he had matured enough to alter his approach. Insults that once might have inspired shouting matches or fisticuffs he instead just ignored.

“That comes from my mom,” McGee said. “When I was young, I’d get mad at myself and feel like it was somehow my fault. Now I don’t get angry anymore. I’ve learned not to focus on stuff other people say because it doesn’t really matter.”

*****

Something else that helped temper McGee’s anger was finding an outlet where he could feel normal alongside his peers. He gravitated to organized sports as a seventh-grader in South Carolina, excelling in football, basketball and track and field.

Minimizing the impact of his disability was harder for McGee in basketball than it was in other sports. He dedicated himself to learning to bounce the ball with his left hand, to extending his shooting range and to perfecting a crossover dribble.

“Learning to go left and to crossover was the toughest,” McGee said. “That’s the only thing that took awhile. When I was younger, I used to get frustrated a lot, but I learned to keep working on it. If I messed up, I’d just keep on doing it.”

McGee and older brother Matthew are polar opposites in everything from tidiness, to study habits, to demeanors, but a passion for sports and a fierce competitive streak are two traits the siblings have in common. Their attempts to one-up each-other made both brothers better, with wisecracking Matthew never shy to rub in his victories and stone-faced Elijah preferring to let his performance do the talking.

“Everything I do is for my mom. I want to provide for my family through basketball.” — Elijah McGee

By the time Dowling uprooted her family and moved back to her native Southern California in 2016, McGee had blossomed into a proficient basketball player. His future travel ball coach didn’t even notice McGee’s disability the first time he watched the gifted young guard score a torrent of baskets for Cabrillo’s JV team.

“When he showed me, I was in shock,” Lam Sam said. “I told my wife and my sons, ‘Look, there’s a kid out there with one hand dominating the game.’ ”

When Lam Sam invited McGee to join his team, the newcomer had just one condition. McGee told Lam Sam he didn’t want to be treated differently than any of his teammates because of his disability. He wanted to earn playing time via his performance, not pity.

McGee quickly emerged as one of the mainstays of Lam Sam’s travel ball program, but he had a more difficult time making an impact for his high school team. Cabrillo’s former coaches never called him up to the varsity team as a junior even though the Jaguars staggered to a 3-18 record last season and McGee piled up points for the JV squad.

“I don’t know why he was on JV,” Lam Sam said. “I still don’t understand to this day. I think the coaches probably had their favorites before he moved here, but there’s no way he should have been playing at the JV level with the talent he has.”

The fresh start McGee needed arrived last April when Hawkins returned to his alma mater and took over the basketball program. Hawkins recognized McGee’s ability and competitiveness the very first time he saw him play, though the new coach did wonder why the guard kept laying the ball up with his right hand from the left side of the basket.

“We were doing 3-man weave drill from the left side, and I was getting annoyed,” Hawkins said with a laugh. “Eventually, I looked closer at his hand and I realized he was compensating. From that day forward, I never said anything about left-handed layups again.”

*****McGee has earned respect around Long Beach with his play this season, but scholarship offers from colleges have been slow to follow thus far. Many Southern California college coaches remain unfamiliar with him because he moved from South Carolina only a couple years ago, he doesn’t play for a prominent high school or AAU program, and this is his lone season of varsity basketball.

If a four-year college doesn’t show interest in McGee in the coming months, playing for a local junior college could be a fall-back option. A junior college coach familiar with McGee told Yahoo Sports that the senior guard “absolutely has the size, ability and skill set” to play beyond high school.

Securing a college scholarship is of the utmost importance to McGee because he views basketball as a means of someday providing for his family. He hopes to either play professional basketball or use his college degree to earn a living in another field – architecture is his top choice for now since he’s also a gifted artist.

“Everything I do is for my mom,” McGee said. “I want to provide for my family through basketball.”

For a proud mother who has dedicated much of her adult life to her two sons, McGee’s mentality is both touching and tragic. Dowling wants McGee’s basketball ambitions to be fueled by his passion for the game, not the need to offer her financial support.

“One of my fears as his parent is that he’s pushing himself hard because he’s worried about me,” Dowling said. “I think he wants to put himself in a position to take care of me, but I don’t want that to be it. I want him to play hard because he loves the game and he loves to play basketball.”

Stressful as McGee’s scholarship chase is for Dowling, it’s still a good problem to have compared to the ones she anticipated the day he was born.

“He’s come so far from the moment the doctor put him in my hands and said there’s something wrong with him,” Dowling said.

Seventeen years ago, Dowling feared McGee’s disability might prevent him from ever pursuing his dreams or leading a normal life. Now, she can only watch in awe as he demonstrates that two hands aren’t a requisite for basketball success.

More from Yahoo Sports:

• Coach Reid: Chiefs star wasn’t warned he was offside

• NFL investigating alleged laser incident involving Brady

• Soccer star was on missing plane, no survivors expected

• Saints’ Thomas calls for do-over of controversial NFC game