On Hockey: Blackhawks fallout furthers overdue NHL reckoning

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The scandal that rocked the National Hockey League this week began more than a decade ago, and it's part of a painful, overdue reckoning that has transformed the sport over the past two years.

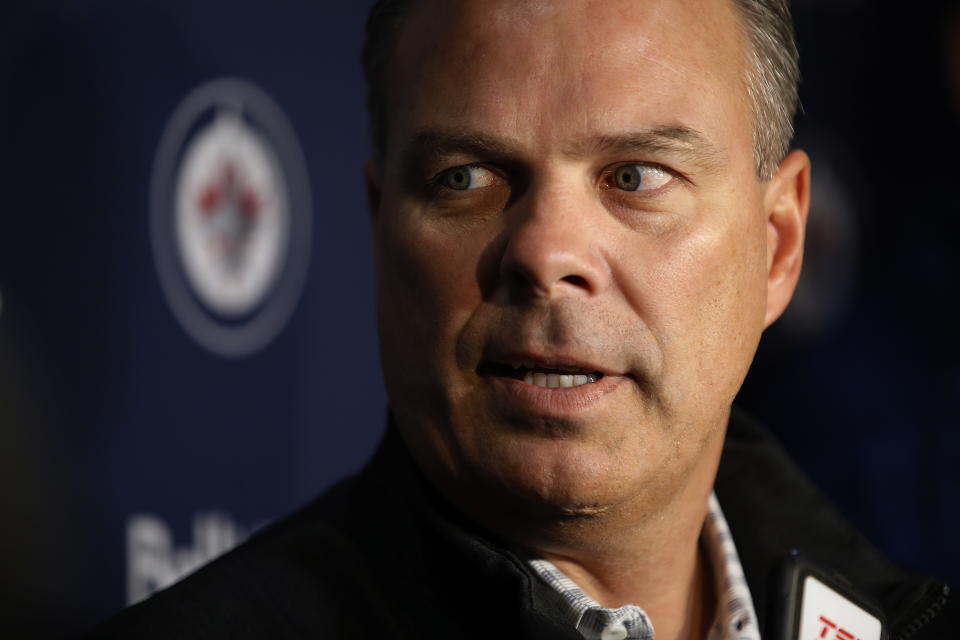

Gone is Joel Quenneville, who has won the second-most games of any coach in NHL history. So is Stan Bowman, the general manager of three Stanley Cup-winning teams in Chicago, along with a fellow executive from the Original Six franchise that is now picking up the pieces from the fallout after being slapped with a $2 million fine by the league.

Already sidelined are Bill Peters, the coach of the Calgary Flames who resigned in 2019 after it emerged that he made racist remarks to a player while in the minors, and Don Cherry, the once-beloved face and voice of hockey in Canada who was fired for an inappropriate rant about immigrants.

All of this and more has forced the NHL to confront coaching practices and matters of systemic racism and misbehavior in a sport where coaches have ruled with iron fists and conforming is the expectation.

No more.

The players are speaking out, on social media and in lawsuits and beyond, finding the courage to crack and perhaps end the sport’s century-old engrained culture of silence.

“It’s an awakening,” former player Anson Carter told The Associated Press by phone Friday. “It’s not going to be easy. It’s not going to be pretty. There’s a lot of heavy lifting. A lot of things are going to happen within the game that are going to make people uncomfortable and they’re not pleasant, but at the same time, we have to go through this if we’re really going to make hockey a sport that’s inclusive and a safe place.”

The overwhelming evidence shows it has not been a safe place for many dating back quite some time.

Players accused Graham James of sexual abuse in the 1980s and '90s, and the disgraced junior coach pleaded guilty to two counts of sexual assault involving more than 300 encounters.

Blackhawks prospect Kyle Beach accused video coach Brad Aldrich of sexual assault in 2010, and at least one coach and a handful of executives who looked the other way are now out of the league after an investigation revealed their blatant mishandling of the case.

A former teammate of Beach's, Akim Aliu, spoke up two years ago about his experience with Peters and the aftermath prompted the NHL to invest time, energy and resources into combating racism in a league that’s still over 95% white. Aliu's lawyer, Ben Meiselas, said the investigation into systemic racism the league pledged to undergo at the time still has not happened.

Beach reached out to Aliu by text, crediting Aliu for being an inspiration in providing him the courage to go public in telling his story.

Aliu's story also created a domino effect, putting successful coaches like Mike Babcock and longtime Quenneville assistant Mike Kitchen on the defensive for mentally or physically abusive tactics. The stuff that hockey used to tolerate from those in power wasn't acceptable anymore.

"We’re starting to weed out the iron fist generation, which was unacceptable in the first place," said goaltender-turned analyst Corey Hirsch, who has become a mental health advocate in recent years. “There’s a peer pressure to shut the hell up. It’s in the locker rooms. It comes from management. It comes from everywhere.”

Agent Allan Walsh, a vocal critic of Commissioner Gary Bettman, believes it comes from the NHL office, as well. He points out that the crises that prompted change emanated from the players, and he would like to see some systemic changes beyond reacting to each situation when it arises.

“Every time we’ve seen change occur it’s been effectuated from a revelation that has shocked people’s conscience, and that has been the motivator for change,” Walsh said. “You’re not going to see culture change from the ground up. Culture, it has to be changing from the top down.”

Carter, co-chair of the league's player inclusion committee that started last year and now a TNT analyst, believes Bettman and other leaders are committed to meaningful change. Around rinks this week, players and coaches made it clear it's overdue.

Boston forward Taylor Hall called out the hockey establishment for being an “old boys club.” Interim Florida coach Andrew Brunette, who replaced Quenneville, said this is "too good of a game to have it stained" and added, “We’re better than that.”

Better than the 2010 Blackhawks, who Hirsch said sold their soul — "for a trophy.” Win at all costs is part of hockey's fabric, though this week — and the past 24 months — revealed what the potential price can be for keeping something quiet in the locker room.

“There’s things you keep in the locker room, and there’s things morally you can’t,” said Dallas coach Rick Bowness, who at 66 is the oldest person behind the bench in the NHL. “Every one of us in this league has learned a very, very tough, tough lesson. And that people that come to work for us, we got to protect them. That’s our job.”

From Peters to Quenneville, Bowman and others, jobs were lost, and they probably won't be the last because hockey may only be beginning of a very difficult introspection about its past and ensuring change — even if it takes a generation.

“That’s the only way we’re going to grow and move forward,” Carter said. “We can’t ignore a lot of the negative stuff that has happened in the past, but at the same time, we can’t just have our head in the sand about it, either.”

___

AP Hockey Writer John Wawrow and AP Sports Writers Stephen Hawkins and Tim Reynolds contributed.

___

Follow AP Hockey Writer Stephen Whyno on Twitter at https://twitter.com/SWhyno

___

More AP NHL: https://apnews.com/hub/NHL and https://twitter.com/AP_Sports