They held a ‘read-in’ at a whites-only library in 1961 and helped end segregation. Meet the Tougaloo Nine.

USA TODAY’s “Seven Days of 1961” explores how sustained acts of resistance can bring about sweeping change. Throughout 1961, activists risked their lives to fight for voting rights and the integration of schools, businesses, public transit and libraries. Decades later, their work continues to shape debates over voting access, police brutality and equal rights for all.

JACKSON, Miss. – Ethel Sawyer sat at a table facing the huge windows, watching the crowd swell outside the public library. She saw their mouths moving. She couldn’t hear the words, but their grimaces made her cringe.

She watched them shake their fists and point toward the building. She looked down, pretending to read. The book was upside down.

Sawyer quietly pleaded that police would hurry, please hurry, and arrest her for taking a seat in the whites-only library. She’d rather go to jail than face the crowd gathering along the sidewalk on State Street.

That morning, Sawyer, 20, a junior, along with eight fellow students from Tougaloo Southern Christian College, a private, historically Black school outside Jackson, walked into the public library designated for white patrons only. It was March 27, 1961, in Jackson, the capital of Mississippi, where the Ku Klux Klan reigned, bombings of Black churches were frequent and the number of lynchings was the highest in the country. State officials had created a commission to track civil rights activists.

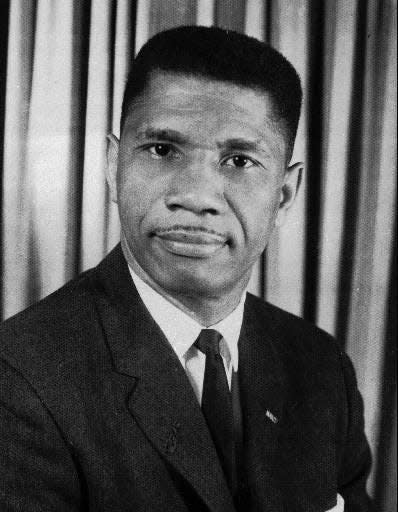

The “read-in” led by the students who became known as the Tougaloo Nine inspired young people across Mississippi to take action, setting the stage for demonstrations at other Black colleges and galvanizing a community around the fight for civil rights. The Tougaloo students were mentored by Medgar Evers, Mississippi’s NAACP field secretary, in a push by civil rights groups to harness the energy and passion of young people in Mississippi and beyond.

Few dared to challenge an entrenched system of segregation across the South, particularly in Mississippi, that relegated citizens with brown skin such as Sawyer’s to libraries that often had outdated books or hardly any books at all. The better-equipped libraries, schools and hospitals were off-limits to the state’s Black citizens.

“What they did in that particular moment was set a standard for what would happen after and set a precedent for youth activism,” said Daphne Chamberlain, a civil rights expert and history professor at what is now Tougaloo College. “They actually set aside their fear because they understood the implications of being involved in the movement.”

The daring demonstration forced Mississippians to reckon with racial segregation.

“This moment of the Tougaloo Nine shocking the consciousness of Mississippians – Black and white – in 1961 is an important moment,” said Robert Luckett, a history professor at Jackson State University.

Police arrived quickly at the Jackson Municipal Library that morning. They ordered the students scattered at different tables to go across town to the colored library.

“This is an unlawful assembly, and you’re ordered to disperse, to leave,” the sheriff commanded.

The students kept still. They were arrested for “breach of the peace” and paraded past the crowd outside shouting at them, cursing them.

Flanked by police, Sawyer threw her head back, tilting her chin toward the sky, snubbing her taunters.

“The heck with you,” she thought.

‘He knew we were in danger’

Jerry W. Keahey fiddled with his grits, eggs, bacon and toast slathered with grape jelly. He was nervous. The student from Laurel, Mississippi, had less than two months to graduate from Tougaloo, and that day’s lesson couldn’t be taught in a classroom.

The Rev. John Mangram, the school chaplain, summoned Keahey and a small band of students to the lobby of a girls’ dorm to pray for their safety. “He knew we were in danger,” Keahey said.

Keahey, a photographer for the yearbook, came armed with the Speed Graphic 2X3 camera he bought for $60. He had scraped up $3 to put it on layaway the year before.

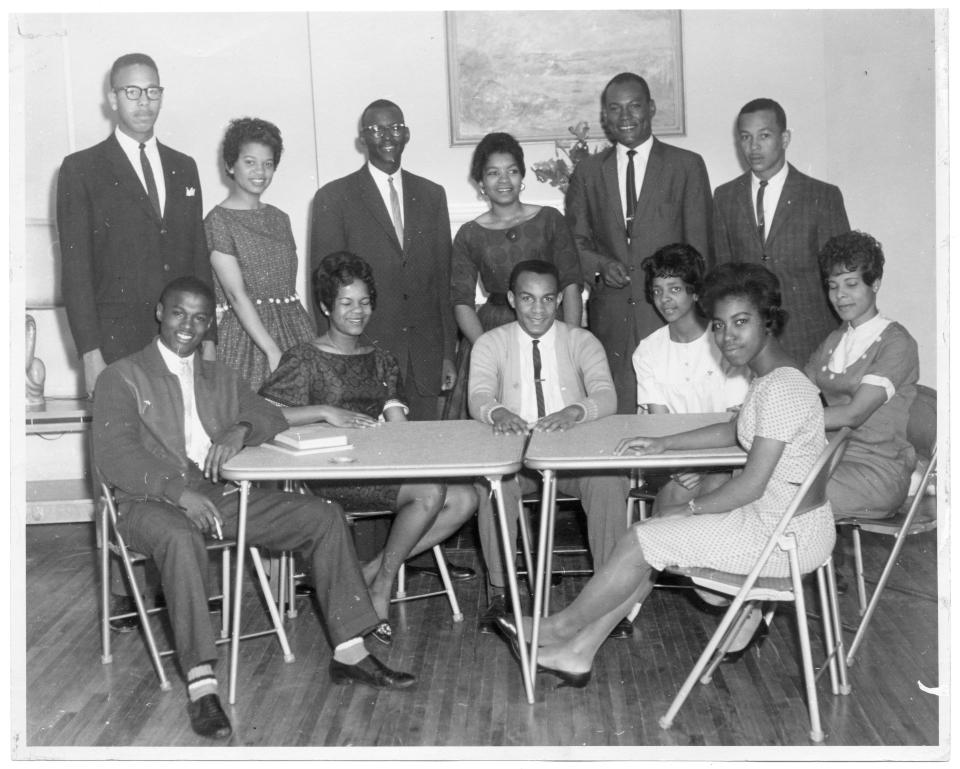

They posed for the camera: Meredith Anding, James "Sammy" Bradford, Alfred Cook, Geraldine Edwards (now Edwards-Hollis), Janice Jackson (now Jackson Vails), Joseph Jackson, Albert Lassiter, Evelyn Pierce and Sawyer (now Sawyer Adolphe).

Click. Keahey took a picture of them standing against a wall. Click. Another with some sitting.

What the students were about to do was unheard of.

They loaded into a yellow-and-white station wagon parked out front. Keahey got behind the wheel.

“There were other people who wanted to go. But I could only get nine people in that station wagon,” he said. “If I could have put 20 people in a bus, it might have been the Tougaloo 20.”

‘We have a right to be served just like the whites’

Only a few people were in the library that sunny morning. Joseph Jackson, 23, asked the clerk for a book he knew was there.

“This is a whites-only library, and you would be accepted at the colored library on Mill Street,” the clerk told him.

Jackson was president of Tougaloo’s NAACP Youth Council. He was a pastor and a philosophy and religion major. Jackson, an only child, grew up in Memphis. His mother cleaned houses for white people. His father was a janitor.

He refused to leave the library.

On the way there, Jackson and the other students had stopped by the George Washington Carver library, which served Black readers. They knew the books they wanted weren’t there.

“We have a right to be served just like the whites,” Jackson recalled.

When it was her turn, Hollis asked for a health book. Everything seemed to stand still as she looked into the faces of white staffers.

“They were like, ‘Look at these folks. They have the audacity to come in here,’” Hollis said.

Hollis, whose father was a minister, prayed for strength. There was so much uncertainty. What would be the price for challenging her state’s long history of segregation?

She wore layers to help shield against potential blows: a black-and-white checkered jacket with three-quarter-length sleeves, a round collar and black buttons down both sides of the front, a black skirt and trench coat with a matching hat. She had designed and sewed most of the outfit – a skill she picked up in a high school home economics class in her hometown of Natchez, Klan territory.

“We had to be ready for the things that we knew had happened to so many other young people, and that is to prepare our bodies because we didn't know whether it would be a billy club or a butt of a revolver or whatever,” she said.

‘Everybody was nervous and scared’

Across the street in a phone booth, Keahey called Mangram on campus about 10 miles away to report what was happening.

“Are the students OK?” Mangram wanted to know.

“They seem to be all right,” Keahey replied.

Police cars with sirens blaring came from all directions. “As though somebody robbed the bank,” Keahey recalled.

Hurry back to campus, Mangram told him.

They didn’t want the station wagon confiscated. Keahey had parked in a Sears and Roebuck lot, hiding it between cars. The school name was emblazoned across its doors.

He drove the back roads to campus, troubled he didn’t know what would happen to his schoolmates.

“Everybody was nervous and scared,” Keahey said. “When you start doing something like that back in the ’60s, you got killed.”

‘You could be killed any minute’: Civil rights veterans share horrors of battling white supremacy

Americans stood up to racism in 1961 and changed history. This is their fight, in their words.

They wanted justice, revenge

Three days a week, Tougaloo students participated in mock mob training to prepare for sit-ins and other protests. They called each other slurs. They shoved fellow students off chairs and poured water over their heads.

“They would do everything they could to really provoke a reaction,” said Jackson, the NAACP youth leader.

For weeks leading to March 27, students filled the polished wooden pews in the campus chapel, talking about students across the South challenging segregation. Evers sometimes joined them, as did Martin Luther King Jr. and Fannie Lou Hamer, an organizer with the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, a pivotal civil rights organization in the 1960s.

Tougaloo provided a safe haven for activists.

Off campus, Black Mississippians were banned from white schools, white sections of bus stations. They had to pay poll taxes to register to vote. Many descendants of enslaved Black Americans worked as sharecroppers for little to nothing for white landowners on former plantations.

Civil rights activists who went to register Black citizens in Mississippi called it the apartheid of the South.

In the 1960s, Black people made up half the population in Mississippi, but only 6% were registered to vote, Luckett said. Mississippi had last elected a Black congressman in 1883.

“It's not to say that things weren't happening in Mississippi,” Luckett said of protests. “Medgar Evers was doing yeoman's work across the state prior to that. It's just there wasn't the kind of spark that really ignited the movement in the way that 1961 would here.”

In January, Evers told students of plans to integrate the library. About 15 members of the NAACP Youth Council met to map out details.

Years before, Sawyer had rejected a request from the NAACP in Memphis to try to integrate Memphis State University. Sawyer, one of 13 children, was the first in her family to finish college. Her father was a railroad freight handler and her mother a homemaker who occasionally cleaned houses for white families.

Sawyer wouldn’t say no to another chance to battle segregation.

“Wherever it was decided that we would go, I would have gone,” she said.

As a child, Jackson had buried the pain of watching a white Greyhound bus driver hit his mother so hard she fell to the ground. At 10 years old, he could only help his mother, whose face was bloodied, to the back of the bus where Black passengers were forced to sit.

By 1961, Jackson wanted revenge.

“I couldn’t wait to step into that white-only library,” he said.

Deborah Berry: I'm blessed to hear living Black history from our civil rights veterans

They tried to eat at a whites-only lunch counter in 1961. They were sentenced to a chain gang.

‘I thought I was going to die’

One by one, students were led into a small room in the jail and repeatedly asked, “Who was your leader?”

Police were sure Evers was involved, but he didn’t go to campus that morning or the library.

“Why do you think we students didn’t do this ourselves?” Sawyer told the two white men. One had his foot on her chair.

“Because you’re not smart enough,” one replied.

“I’m tired of your 10-cents psychology,” said Sawyer, a sociology major. “And I want my lawyer.”

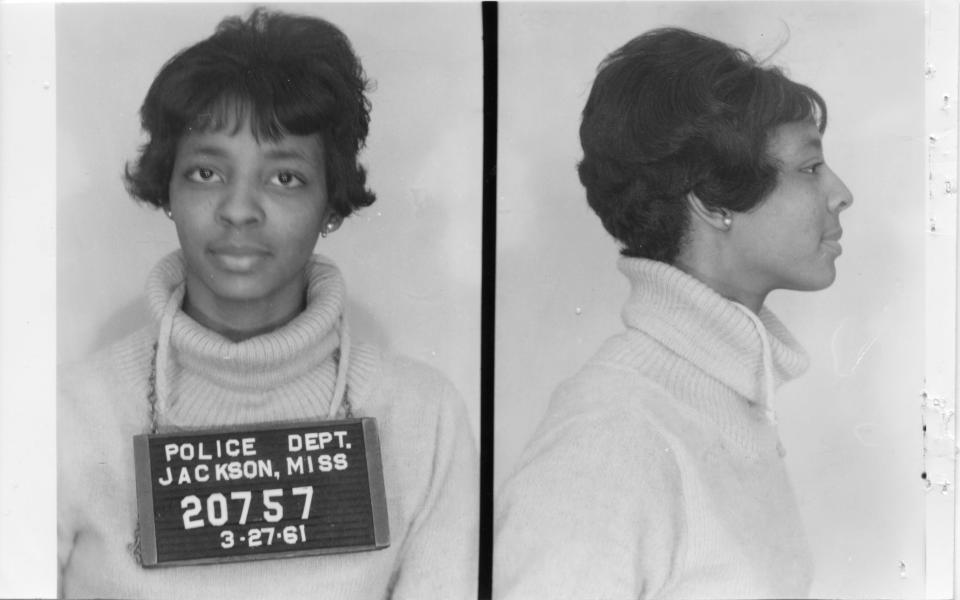

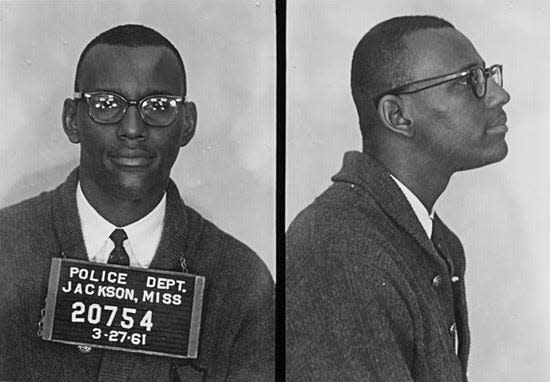

The students were booked. Mug shots taken.

Jackson was #20754. Alone in his cell, he realized he wouldn’t be released that night as organizers had promised. He thought about his wife and two young children back in Memphis. He couldn’t sleep, fearing the KKK would drag students out and bury them in unmarked graves.

“I thought I was going to die,” he said.

‘The cruelty of segregation’

Word spread to Jackson State University that Tougaloo students had been arrested. The historically Black college was a few miles from the library and from Tougaloo.

Joyce Ladner, 16, a freshman, cut class and waited by the radio for word about the students.

“It was incredible news for Mississippi,’’ she said.

Ladner and her older sister, Dorie Ladner, were the first in their family to attend college. Their mother was a homemaker and their stepfather a diesel engineer. The sisters from Palmers Crossing had often visited Evers in his office across the street from campus.

At the NAACP office weeks earlier, Evers had sworn them to secrecy about the Tougaloo students’ plan. He suggested they propose a “sympathy protest” on their campus.

The evening of the library demonstration, the Ladners joined hundreds of students on the Jackson State campus for a prayer vigil for the Tougaloo Nine.

“Lord, we have trouble here,” one student prayed. ”Watch over those students who are in jail.”

It was interrupted, Dorie Ladner said, when the college president rushed toward them shouting, “Stop it. Go back to your dorms!”

He knocked her sister’s roommate to the ground.

The state-funded school had much to lose from students defying Mississippi norms.

“This is the cruelty of segregation,” Joyce Ladner recalled.

Police showed up with dogs, and students retreated to their dorms. Plans were set to march to the city jail the next morning.

‘Oh, my Lord, they’re trying to kill us’

Dorie Ladner didn’t expect the wall of white police just steps off campus when about two dozen students from Jackson State began their march to the jail.

That same day, thousands of people, some dressed in Confederate regalia, were in the city to celebrate the centennial anniversary of the Civil War.

The Jackson State students turned off Lynch Street and down side streets.

At the corner of Pearl and Rose Streets, Joyce Ladner heard pop, pop, pop. “Oh, my Lord, they're trying to kill us,” she thought.

The officers were firing tear gas. Students ran through the neighborhood.

A cartridge slammed into Dorie Ladner’s back. She raced down Rose Street when a Black woman shouted, “Baby, come and sit on the front porch!”

“Sit here like you live here,” the woman commanded. “Don’t move.”

Dorie Ladner watched police and their dogs walk up and down streets.

Her sister ran down an alley and knocked on the door of a shotgun house. When no one answered, she reached through the screen to let herself in and quickly explained to the approaching woman what was happening.

“Come on here, nobody's gonna bother you in my house,” the Black woman told Joyce Ladner and a schoolmate.

A student, who had been hiding on the back porch behind a refrigerator, knocked on the door. The three sat still as the woman continued to iron.

“It's a low-down dirty shame that they're treating these children like animals,” the woman said.

Black activists travel the South to push for voting protections, honor Freedom Riders

She helped integrate higher education in the South. And her classmates wanted her dead.

Youth activists flock to Mississippi

More than 35 hours after they were jailed, Sawyer and the other students were released. She walked through the station eyeing the cakes, cookies, candy and fruit locals had dropped off for the students. It felt good to see the community support.

Police drove the students back to campus – speeding so fast Sawyer thought they would be killed in a car crash. Other activists had been murdered by segregationists along Mississippi roads.

“I believe that we were taken back in those police cars to save our asses,” Sawyer said.

At the courthouse the next day, Sawyer saw a crowd of Black people waiting outside, many unable to get into the packed, segregated courtroom. Onlookers, mostly women and children, applauded as the Tougaloo students headed into the building.

Police sicced dogs on the supporters and beat some with nightsticks and pistols. A pastor was bitten by a dog.

Inside the courtroom, the students were convicted, each fined $100 and issued a 30-day suspended jail sentence.

In the weeks that followed, local newspapers labeled them agitators. The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, a state agency tracking activists, sent investigators to students' hometowns to dig up information.

“She has good records in school and a good reputation in the community,” an investigator wrote of Sawyer.

In Natchez, Klansmen rode horses into Hollis’ father’s business to intimidate them.

“They didn't have to say anything with their white hoods on their head,” Hollis said.

At Jackson State, Dorie and Joyce Ladner were expelled for their civil rights involvement. They enrolled at Tougaloo and worked with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

At Tougaloo, the nine students were featured on the front of the Tougazette. “Tougaloo 9 Honored Here and in North,” the headline read.

Other young activists turned their attention to Mississippi, where hundreds of Freedom Riders braved violence to help end segregation in public transportation.

Farther south in McComb, Mississippi, two young activists were arrested that summer for sitting at a whites-only lunch counter in Woolworth’s department store. In October, more than 100 high school students marched to City Hall there.

“Young people said they had absolutely nothing to lose,” said Chamberlain, the Tougaloo professor.

Today, a marker honoring the Tougaloo Nine stands outside the old library, abandoned and gray with age. This year, Tougaloo College awarded the students honorary doctorate degrees.

Sawyer, 81, has no regrets. “Not a one,” she said. “I‘d do it again. I’d do it 10 times.”

To report these stories, USA TODAY interviewed veterans of the civil rights movement, historians and witnesses and reviewed public records.

Explore the series

Americans stood up to racism in 1961 and changed history. This is their fight, in their words.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: The Tougaloo 9: How Black youths helped end segregation in libraries