'I had seen that smirk before': Vestiges of slavery still haunt our legal system

Congress passed the KKK Act to combat racial terror. But the Supreme Court insists on shielding public officials who harm Black people.

Editor's note: This column includes graphic details.

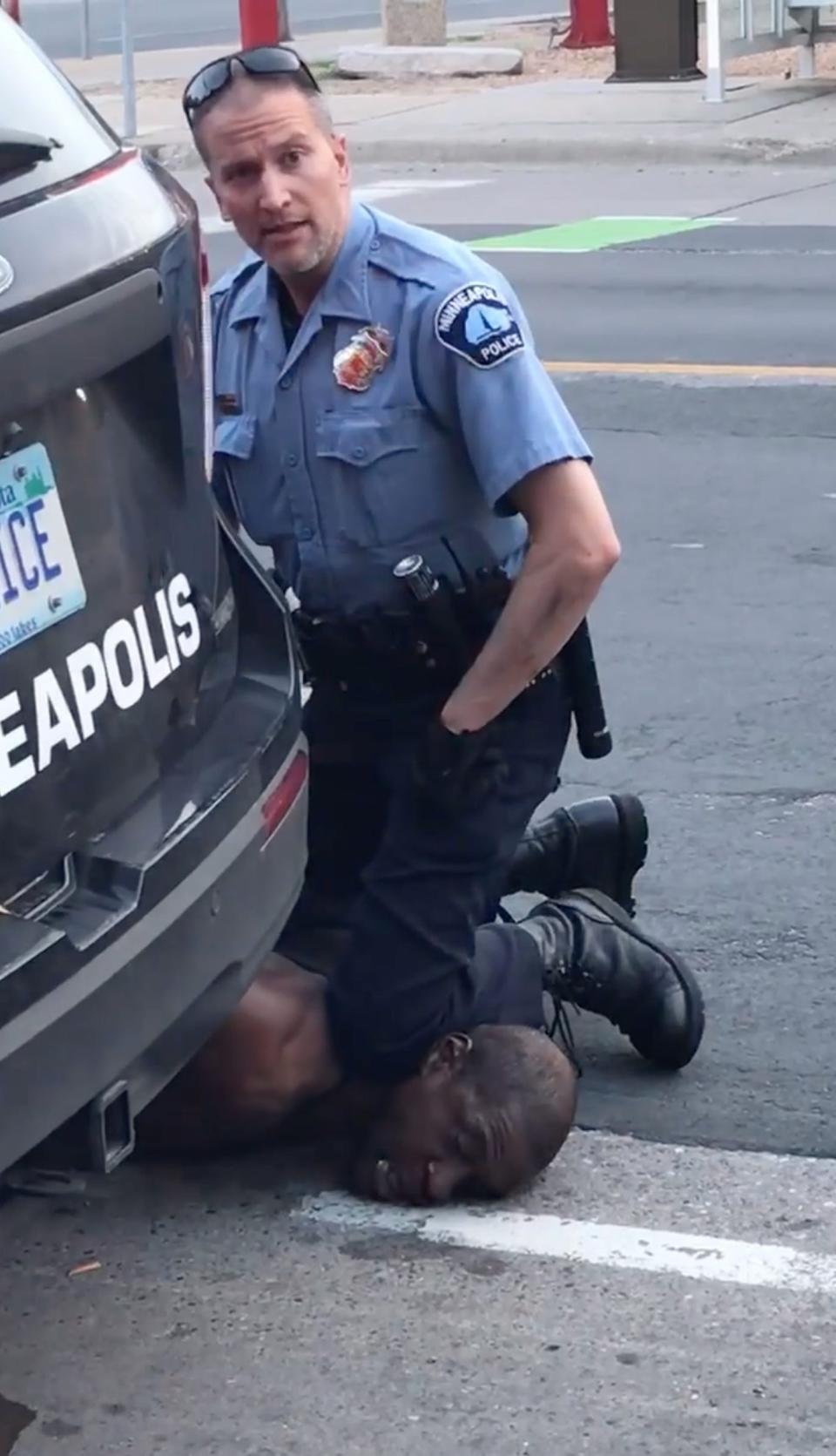

It has been more than a year since I watched Derek Chauvin murder George Floyd. Of the many haunting moments from that video, it still strikes me that as Floyd and witnesses pleaded with Chauvin to stop, the then-officer and now convicted murderer looked directly into bystanders’ cameras and smirked. That disquieting, macabre smile reflected a murderer certain that he would escape accountability.

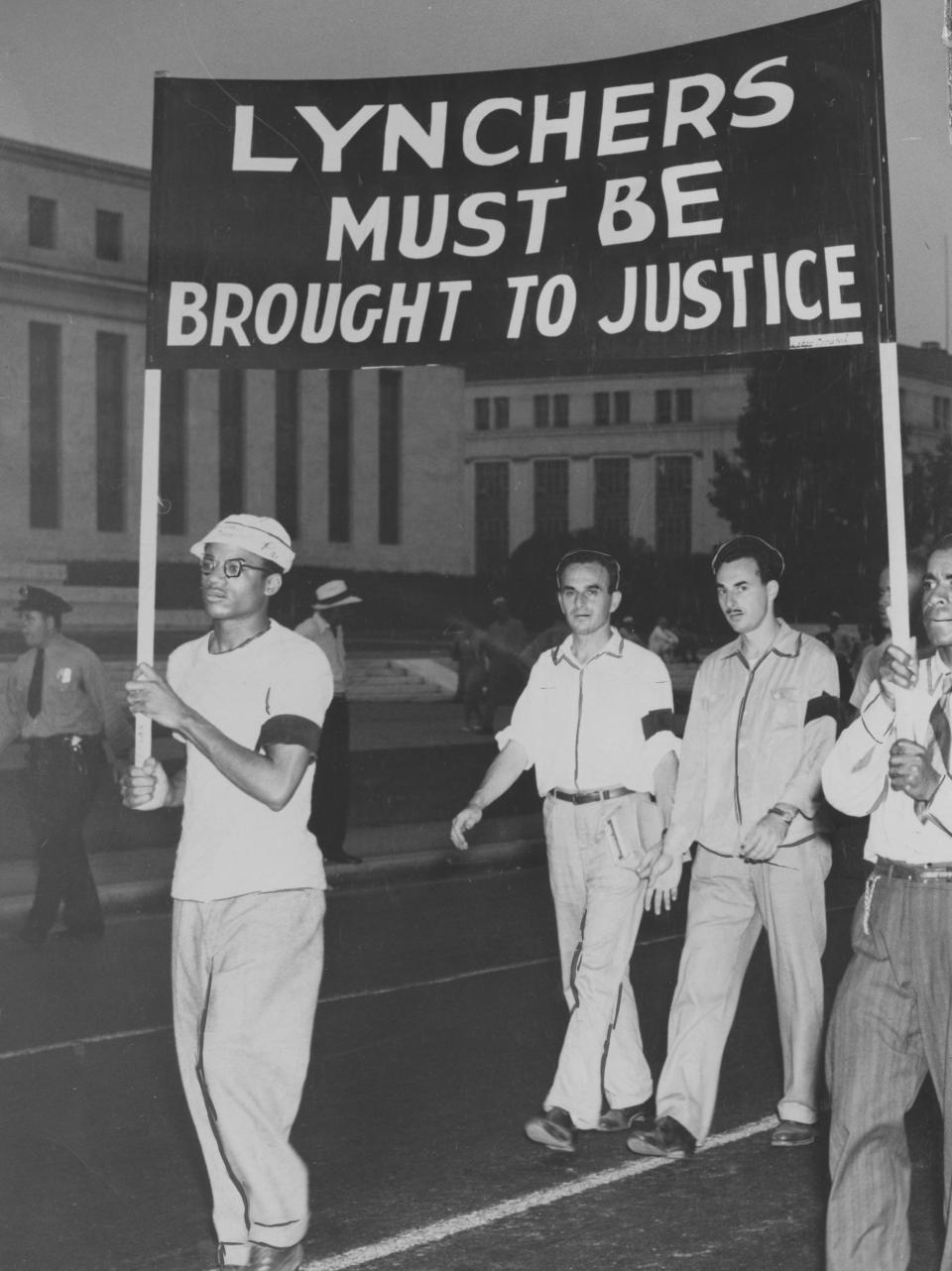

I had seen that smirk before. The same bemused grin appears in 18th and 19th century lynching photographs, featuring white people smiling as Black bodies burned or hung just feet away.

What manner of evil gave these killers – their smiles separated by more than a hundred years – the courage to torture and kill knowing that cameras were watching? The answer lies in a centuries-old system of white supremacy that has rarely punished state assaults on Black bodies. And key to this system has been the Supreme Court’s insistence on shielding government actors who harm Black people from liability.

To fully grasp the perniciousness of qualified immunity, you need to understand the genesis of Section 1983 – the federal statute Congress enacted as a remedy for victims of state violence – and the Supreme Court’s role in destroying it.

Rampant white terrorization of Black people

The road to Section 1983 began with the institution of slavery, which incentivized and tolerated unspeakable violence against Black people. The Supreme Court placed its seal of approval on slavery in its Dred Scott decision in 1857, declaring Black people “beings of an inferior order” who “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect,” and putting the nation on the road to war.

The Civil War, in which nearly a million white men laid their lives on the line in defense of white supremacy, ended slavery and birthed a period of Reconstruction.

Freed Black people, determined to cast off the vestiges of slavery, established schools and churches and amassed political and economic power.

Reconstruction offered a glimpse of a new America that many white people simply would not abide. Southern whites set out to “redeem” the Confederacy by washing the land in blood. White terrorists burned Black schools. Destroyed Black churches. Crushed Black businesses. Defiled, mutilated and murdered Black bodies.

The Equal Justice Initiative has documented nearly 2,000 lynchings in the decade following the Civil War.

The lynchings were accompanied by massacres that left hundreds of Black people dead in communities throughout the South. These crimes were often carried out by state actors – police officers, state militia members and politicians – and were ignored by Southern states that refused to penalize the terrorists.

Black people resisted the terror. When Congress commissioned an investigation into Reconstruction violence, Black people risked their lives and livelihood to publicly testify about the horrors they had endured. Led by the Joint Committee to Inquire into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States, the Ku Klux Klan hearings represent one of the largest congressional investigations in American history. The testimony spans more than 13 volumes in the congressional record.

Hannah Tutson of Florida testified that Klan members raped and whipped her “from the crown of my head to the soles of my feet” until “blood oozed out through my frock all around my waist.”

Betsey Westbrook of Alabama testified that white men attacked and killed her husband in front of her and her young son in their home. Minister Elias Hill of South Carolina testified that Klansmen dragged and savagely beat him.

The details differed, but the general stories were the same: White terrorists violently raped, murdered and assaulted Black people, and state governments looked the other way.

Congress passed the KKK Act. The court curtailed it.

Against this backdrop, Congress passed the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871. Through Section 1, now known as Section 1983, Congress armed victims of constitutional violations with the ability to seek damages in federal court.

Section 1983 was rarely used for nearly a century after its enactment; for Black people, testifying against white people in court – much less filing suit – was tantamount to suicide. After Black people began to bring suit under Section 1983 during the civil rights movement of the 1960s, the Supreme Court invented the doctrine of qualified immunity.

To be clear, Section 1983 makes no mention of immunity. No constitutional provision requires immunity. The common law at the time of Section 1983’s enactment did not recognize qualified immunity.

But through its constant stream of qualified immunity decisions, the court tells police officers – who, as in 1871, are almost certain to avoid criminal prosecution and are highly unlikely to face civil liability in state courts – that even “palpably unreasonable conduct will go unpunished.”

Derek Chauvin pleaded guilty Wednesday to federal charges of violating George Floyd’s civil rights. But on May 25, 2020, the Minneapolis police officer had good reason to believe he'd avoid punishment. He may have been wrong, but most others are not. By consistently protecting state actors from accountability for outrageous conduct, the Supreme Court helped put that sadistic grin on Derek Chauvin’s face.

Tiffany Wright directs the Civil Rights Clinic at Howard University School of Law. She is a former law clerk to Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor and regularly litigates police misconduct cases in federal courts.

This column is part of a series by the USA TODAY Opinion team examining the issue of qualified immunity. The project is made possible in part by a grant from Stand Together. Stand Together does not provide editorial input.

This article originally appeared on Wichita Falls Times Record News: 'I had seen that smirk before': Vestiges of slavery still haunt our legal system