'I guess it's better to talk about it than to be forgotten': The story of the man who replaced Cal Ripken Jr.

Late in another baseball summer, an earnest public-relations man named Geoff handed his phone to Ryan Minor, field manager of the Frederick Keys of the Carolina League.

The Carolina Mudcats are in town. The little ballpark across the street from the cemetery and down the road from the Costco, where Interstate 70 curls before hustling 50 more miles to Baltimore, would hold a nice Saturday night crowd, nearly 9,000.

They’ll play ball in a few hours, after the batting practice and raffle announcements and national anthem and ceremonial first pitch and that ad they run on the video board in left field, the one that celebrates 50 years of Roy Rogers restaurants, 30 years of Frederick Keys baseball and 20 years since Cal Ripken Jr.’s streak ended.

[Yahoo Fantasy Basketball leagues are open: Sign up now for free]

“So, I hear it every single night,” Ryan Minor says. “Makes me feel old. Makes it all seem far away.”

Twenty years. Or about 400 feet. Which all seems about right, time and distance and memory being what they are. So one day soon one of his young men will stand, say, where Adam Jones did just yesterday, or where Manny Machado once did, and he will expect nothing but greatness from himself, nothing but more, and Ryan Minor will have a story about that.

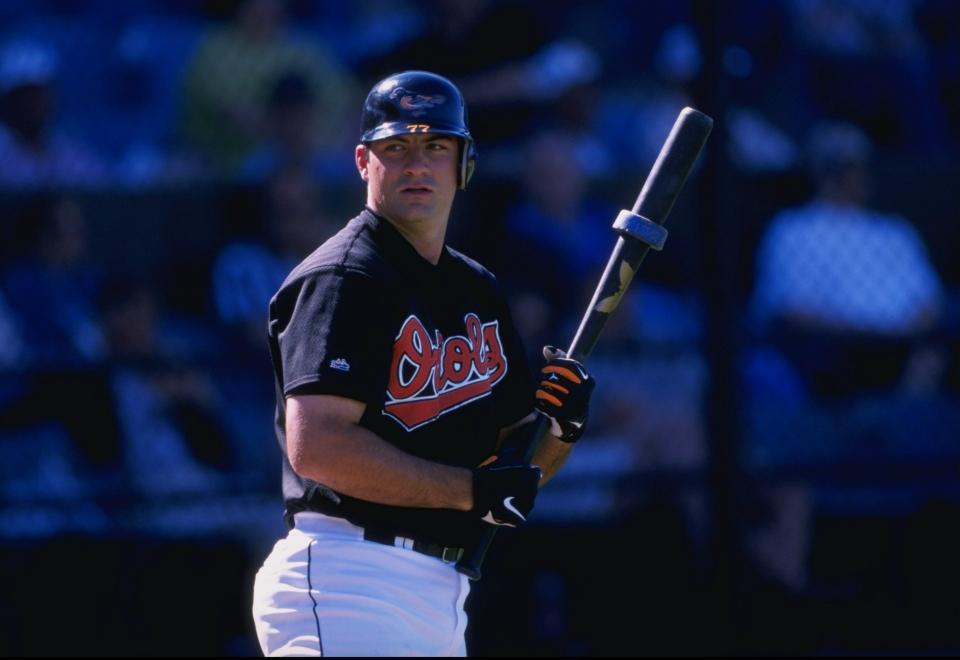

For a span of eight pitches on Sept. 20, 1998, Ryan Minor was, as far as many knew, one of the great ballplayers who ever lived. A legend. An icon. A man with generational toughness and acumen whose career was hopelessly admired, including by Ryan Minor. For those two minutes, Minor stood where Ripken always did, a big guy with broad shoulders and unassuming posture looking close enough like Ripken, on a night in Baltimore when Ripken was supposed to be there. When it seemed he was. Then wasn’t. Minor was.

What Ryan Minor thought for those eight pitches, quite reasonably, was, “Don’t mess it up.”

What the man sitting behind home plate said, his eyes wide and arms splayed in disbelief, he having stood and turned to the press box after five or six of those pitches, was, “Is this it? He’s not playing? Is this the night?”

Minor was the Baltimore Orioles’ next third baseman. Ripken, the day before, had played the last of 2,632 consecutive games, those at shortstop and, by the end, third base. He was not retiring, but this was the first note of a long goodbye, on a Sunday night in September when he’d informed manager Ray Miller he would not play, when Miller told 24-year-old Ryan Minor he had a half-hour to prepare for his first big-league start at third base. This, in essence, would be the first chords of his long hello, the big Oklahoma banger who was to be the future of the Baltimore Orioles.

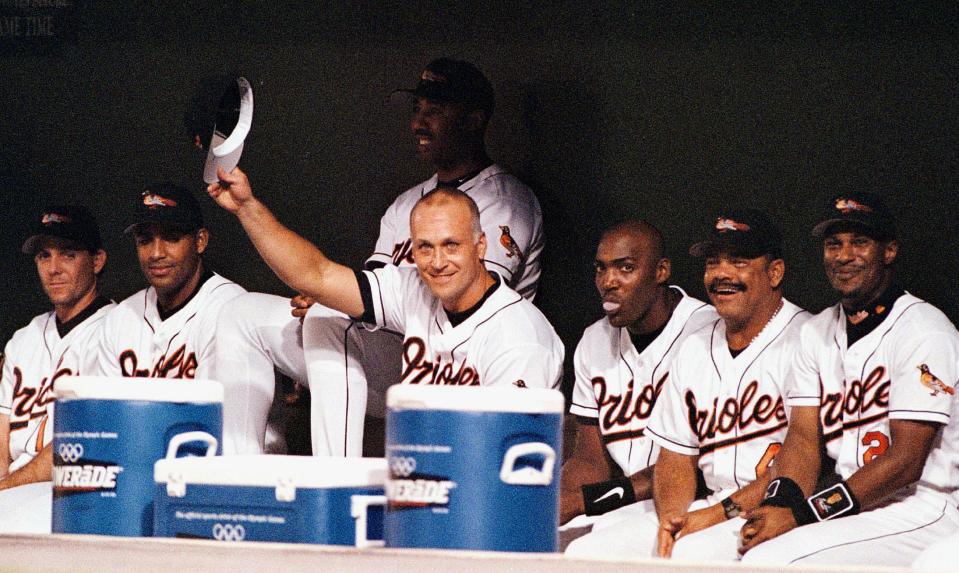

After those eight pitches, players from the third-base dugout, that closest to Minor, came to the top step to applaud Ripken. Ripken himself rose from the opposite dugout to recognize the New York Yankees’ gesture, holding his cap high, then turned to the people in the stands, who then concluded Ripken was not at third base at all, that he was on the bench, that the Iron Man streak would end and they would be witnesses to him not playing baseball, the first of their kind in more than 16 years.

And Ryan Minor went back to being Ryan Minor, 24-year-old third baseman, super prospect, expecting nothing but greatness, nothing but more. Then, time and distance and memory being what they are, it’s coming up on 20 years later. Life’s been good, he says, and even the baseball’s been good, all things considered, even if you do count the .177 career batting average, the years spent chasing greatness in Indy ball, when just good would’ve at least been something, and finally the surrender at 31. The phone rings because there was Cal for forever and Ryan for a minute or two, because there was that night, because he was in that place at that time, and it was glorious until it wasn’t. But at least it was, and most don’t even get that.

“I guess it’s better to talk about it than to be forgotten,” he says. “I like to talk baseball.”

He won’t tell a sad story. He met his wife, Allyson, because he was a baseball player. She’s been a kindergarten teacher at the same school for 22 years. They have two daughters: Reagan is 12 and Finley is 4. Reagan developed meningitis when she was a baby and is developmentally disabled. She is, Ryan says, a battler, and when a man is practicing sign language so that he can keep up with his little girl, because she is practicing sign language so she can enter a little part of the world, that is perhaps when there is no longer time for a sad story. There is, instead, only getting Reagan ready for a new school, where she’ll have a locker for the first time and venture a step further into that world, and getting a roster of young men ready for their lives, too, and the truth is Ryan Minor seems good with all of it.

“It all goes back to not playing as well as I wanted to or could have,” he says. “I put a lot of pressure on myself to live up to that hype. That’s not an excuse for how my career went. … Unfortunately, I didn’t live up to that billing.

“What I’m doing now, all the lessons I learned, I try to instill in these young players. It goes back to my age, things that were good. Things that were right. Fulfill my promise to myself to get these guys to the next level. Make sure they understand the opportunity that’s in front of them. Maybe what I did wrong.”

He laughs, because maybe there is nothing so complicated in any of this, in who Cal was and what he – Ryan – was supposed to be, in what the game makes of men who care too much and don’t care at all, in the few grains of wood that stand between an icon and a guy with a story to tell.

“Hitting is hard,” he says. “It is hard.”

He is in the final hours of another summer. He’s been coaching or managing for longer than he played now, and figures he’ll keep on that path for a while, see how that goes. The major leagues weren’t exactly for him once, but maybe they will be the second time around. He has, after all, spent an awful lot of time thinking about the game. Not just one, either. All of them. All of it.

There are more of him than there are of Cal. Eight pitches are better than none. A little hope was better than none. That greatness he expected, it doesn’t go away. It shifts, gets a bit older, a bit wiser, raises a new generation, and finds a new time and place to be great.

“Obviously, I wanted to do better, be better,” he says. “But I am proud of what I’m able to do every day. It’s a blessing every day I get to get up and do this.”

Then he has to go. There’s a game soon. Another one. The game keeps going. He does too.

“Thanks for calling,” he says.

More from Yahoo Sports:

• Meyer’s grim warning to NFL team about Aaron Hernandez

• School official sorry for racist remark about Texans QB

• New book claims Brady feels ‘trapped’ with Belichick

• Red Sox fans make problematic discovery