'We Got You Back': From the ruins to a revival, North Wilkesboro community embraces racing's return

The soaring vocals and riff-heavy guitars of Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin’ ” blaring through the new public-address system at North Wilkesboro Speedway were almost too on the nose.

The community that had watched the historic race track slowly crumble with each passing drive on U.S. Highway 421 finally had its moment, more than a quarter-century after its most recent date with NASCAR’s major leagues. An open house last week felt like a congregational homecoming and a celebration for a long-overdue restoration of one of stock-car racing’s founding circuits.

The hills that cradle a NASCAR original are ringing again with the thunderous sound of racing, leading up to Sunday’s first running of the NASCAR All-Star Race at North Wilkesboro (8 p.m. ET, FS1, MRN, SiriusXM). It’s an unlikely resurrection for a track once presumed long gone, but a place that will infuse new life into an annual invitational event and the Wilkes County area of North Carolina that it calls home.

RELATED: All-Star Race schedule | North Wilkesboro 101

The track’s life has come full circle for a sport that has returned to the rustic, countryside authenticity of short-track racing. It’s also a direct line into the moonshining roots that prompted the formation of NASCAR some 75 years ago.

North Wilkesboro Speedway is breathing again, in large part thanks to the community that pushed for its return and is now cheering for the place itself and its future.

Here are the profiles of those who have made it happen and those who are cheering its return the loudest.

The podcast protagonists

In late March of 2021, Speedway Motorsports President and CEO Marcus Smith took a seat across from Dale Earnhardt Jr. in front of live microphones. The two went way back, and their easy conversation about the Smith family’s portfolio of tracks was the fodder for a free-wheeling episode of the Dale Jr. Download podcast.

The chat seemed to be winding down when Earnhardt and co-host Mike Davis asked Smith about one or two things left on his list of topics. “North Wilkesboro,” Smith blurted out to the astonishment of his hosts. “I just want to let you know that we haven’t forgotten about North Wilkesboro. We haven’t given up on it.”

“What does that even mean?!” Earnhardt replied.

“It just means that I’m thinking, we’re working on it, no promises, but we have not forgotten about it,” Smith said. “That’s the big message.”

On a cold December day in 2019, the two had spent time with a modest handful of volunteers in clearing the 0.625-mile oval of the rampant weeds that had sprouted up through the dormant racing surface. The clean-up was meant to scan the track for iRacing, preserving it in pixel form. But this podcast proclamation was a glimmer of real-world hope.

“I know a lot of people just think that I don’t care, and that’s not true. I really do care, and if we can think of a way to do something there, we’re going to,” Smith said, adding, “There might be hope to do something there. And you never know.”

Nearly nine months passed when N.C. governor Roy Cooper signed a state budget proposal into law, allocating $18 million to Wilkes County for funding water, sewer and infrastructure improvements to the facility. A day later, Smith released a statement that read in part: “The goal will be to modernize the property so that it can host racing and special events again in the future.” At the same time came a subtle but significant change: North Wilkesboro Speedway joined the Speedway Motorsports masthead alongside the company’s established tracks.

Almost exactly one year ago, Cooper visited the track ahead of a proposed return of grassroots racing in August. Creature comforts were sparse for those events, but few seemed to mind. When Earnhardt participated in the final race of the month, a packed house bathed in an electric atmosphere — on a weeknight, no less.

Most everyone took notice, Smith included. “That was the turning point,” Smith said later. “That’s what made me and Dale say, ‘I think we can do this.’ ” Eight days later, plans for the All-Star Race to be held at North Wilkesboro were revealed.

“We had a ton of grace from the fans, and everybody had a blast,” Earnhardt Jr. said. “Everybody was just so happy to be there, and as soon as the cars started rolling, everybody was like, it was sort of this surreal moment where you’re thinking, ‘Man, I can’t believe that this is happening.’ And I was thinking that in the car and after the race, and I’m like, ‘I just can’t believe that we actually raced here, and that we had such a great turnout, and we had such great energy.’ ”

Smith acknowledged the long-held animosity that Wilkes residents carried toward his family in the days since his father, Hall of Famer Bruton Smith, and New Hampshire track owner Bob Bahre split ownership of the track in the mid-1990s and took North Wilkesboro’s Cup Series dates to new venues. Speedway Motorsports acquired full ownership in 2007, but the stalemate persisted.

Recent events have done plenty to heal that legacy.

“It’s because of the community that we’re here,” Smith told NASCAR.com at the track’s open house. “I mean, Dale Earnhardt Jr. and his big idea of preserving it digitally has exploded into a revival and restoration of a speedway that was forgotten. It was part of the lost speedways, it was dead and gone and left behind. And so it’s very special to see these faces here. You’ve got people here that weren’t even born when this place was last opened, and of course, people that have made many trips here. To be a part of reviving that history, it really turns the speedway into a time machine where people come back and remember days gone by, but also build on days ahead.”

The ‘doer’

Shortly before his death in 2007, NASCAR Hall of Famer Benny Parsons had left for his wife, Terri, a to-do list with ambitious goals. Number one was finishing some needed home-improvement projects. Second was opening a winery, a task that fellow vineyard owner and team owner Richard Childress had encouraged. “Start a vineyard, Benny. It’s easy,” Terri Parsons recalls him saying. “Come on, Richard. Are you kidding me?”

But item No. 3 was the most ambitious, the only one she says she didn’t accomplish right away and the one that became all-consuming: re-opening North Wilkesboro Speedway.

Representatives from the Wilkes County commissioners had enlisted Parsons’ help not long after her husband’s passing, knowing her background as a former director of tourism for the state of Florida and knowing that she was one of a few people with an open line of communication with Bruton Smith, the track’s owner. Parsons had helped acquire permission for a handful of film projects at the speedway — commercials, music videos and the like — but any overtures about revitalizing the facility were rebuffed.

Still, it opened the door for further communication, and Steven Wilson — who helped keep the conversation going with his Save the Speedway movement — urged her not to let the matter drop. Smith began to soften his stance, and his son Marcus was an even more eager listener.

“I said, ‘you do know you’re sitting on the goose that lays the golden egg, right?’ ” Parsons said, giving the younger Smith a vivid history lesson about the track’s instrumental role in the formation of NASCAR, offering proof that founder Bill France Sr., track owner Enoch Staley and a group of local moonshiners had made headway on organizing stock-car racing there — a forerunner to the famous Streamline Hotel meetings.

The next step was rallying local politicians, getting the right elected officials in place and encouraging them all to work together. Parsons’ time spent in the political arena helped present a unified front for meetings with the younger Smith. One such meeting took place just after sun-up at the track, with a group of county commissioners greeting Smith and Steve Swift, Speedway Motorsports’ VP of Operations and Development.

“God, but it’s the history of this place. The stories,” Parsons recalled Swift saying. “He said, look at the hair on my arms. The hairs on my arms are standing up, just being here. There’s something about this place.”

Shortly thereafter, Smith’s appearance on the Dale Jr. Download made one of the first public confirmations that motion at the track was a possibility. After the episode dropped, Parsons’ phone started buzzing from her Wilkes County trustees. Among them was Eddie Settle, a former county commissioner who is now a state senator. “He said to me, ‘Are you listening?’ I said, Yes, sir,” Parsons recalled. “And he said, ‘We need to show Marcus Smith some love. … That’s your wheelhouse. Think of something.’ ”

Less than 24 hours later, Parsons had an answer. Rather than tiptoe around the subject, she chose a direct approach. The resulting campaign simply stated “We Want You Back” in large block letters along with the track’s logo — an asset that she got permission to use through a backchannel. In short order, that message was on billboards along highways, banners in town and on yard signs along the county’s back roads — amplified through social media and the steady drumbeat of local voices.

The clean-up for iRacing was one step, and volunteer efforts within the community offered more help with the upkeep. The grassroots efforts were starting to take hold.

“(Earnhardt) Junior said, you know, maybe this place isn’t as far gone as you think it is, and he really came in and kicked the field goal,” Parsons says. “I sat all of our local people down and said, ‘Look, we each have a role to play in this. Check your egos at the door, because not one of us is more important than the other.’ ”

Seeing the speedway today — with all the care taken to rebuild the track into a modern facility while keeping the old-school touches — stirs Parsons’ emotions.

“What do I think? I mean, it’s daylight and dark,” she says. “Totally daylight and dark. I mean, I can’t go out there without crying.”

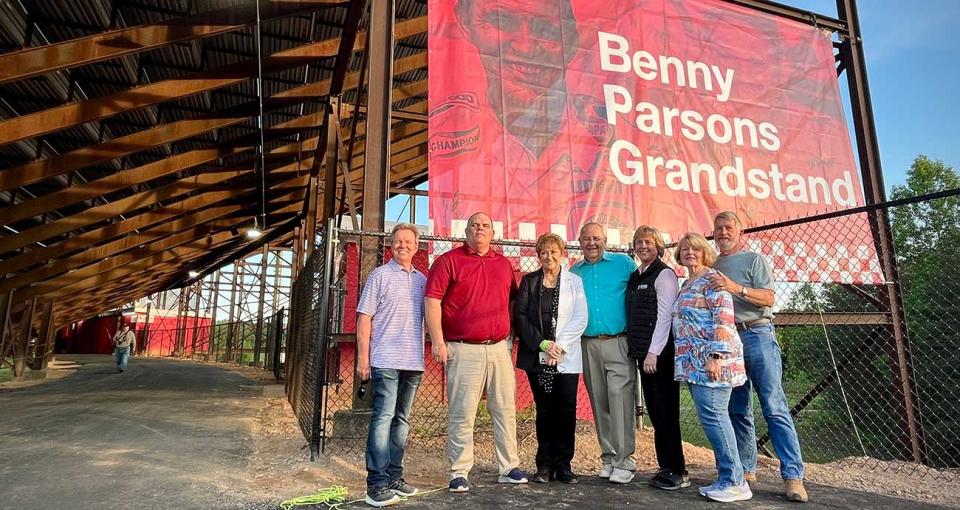

It’s why Parsons was wearing large, dark sunglasses to hide her eyes at the speedway’s open house — even with the sun starting to set behind the mountains. Speedway officials revealed that evening that the arcing seats through Turns 1 and 2 would be rechristened as the Benny Parsons Grandstand, and the family embraced beneath the unfurled banner.

Item No. 3 on that to-do list finally had its checkmark, some 17 years later.

“He was my best friend, and I was his best friend,” Terri Parsons said of her late husband. “And we were always together. So I look back now at that list, and him knowing me as well as he did, I wonder. All these years, I thought he made the list for him. I’m not too sure he didn’t make the list for me.”

The family legacy

Just a few minutes from the race track, Mike Staley opens the office section of his spacious garage. A desk, office chair and couch sit in the center, but it’s the walls and shelves that are filled with racing memorabilia that illustrate how much the speedway is part of his family’s fabric.

Staley was North Wilkesboro Speedway’s track president when it closed in September 1996, but the memories live on in his collection of artifacts. Among the framed keepsakes is another shot of the full-field photo of drivers from the last Cup Series race in September 1996, but with his family in the front row. More than one family member isn’t quite facing the camera at the moment the shutter snapped, catching a glimpse at Jeff Gordon — then a budding superstar and the eventual winner of the final race.

That moment was 50 years after the track was born, inspired by a trip that his father, Enoch Staley, took to see his first stock-car race in South Carolina in 1945. He returned to Wilkes County with the intent of bringing the sport to his home, joining Charlie Combs, Lawson Curry and John Mastin in building the place.

“Somebody had the land, somebody had the money and somebody had the equipment I guess as well,” Mike Staley says. One aspect of the initial construction remains part of the track’s DNA. When the money dried up, so did the ability to pay to have the track properly graded. To this day, the frontstretch runs downhill and back uphill on the back straightaway. “They went to work on it, and they expected 3,000 people and 10,000 showed up.”

The early successes helped the elder Staley become a closer business partner with NASCAR founder Bill France Sr. North Wilkesboro was the finale for the Cup Series’ first season in 1949, and when the schedule nearly doubled in length just two years later, the track became host to two races annually.

The track was a fixture that spanned the Cup Series circuit’s formative eras, including stages of considerable growth in the 1980s and ’90s. ESPN, then a fledgling network with the advent of cable television, was starved for programming during that time and North Wilkesboro’s events were a popular addition to its portfolio of racing coverage.

The industry’s growth in the 1990s signified change that would lead to the track’s final days. When France died in 1992, so did the sense of assurance that Staley’s track would keep its place on the schedule. Enoch Staley died three years later, and Mike Staley succeeded him as track president and chief operating officer.

The reach of the sport was expanding, and new tracks were springing up across the country, hungry for NASCAR events. Those factors, combined with rising purses demands, led the two co-owners to sell. The Combs family sold its half-interest in the track to Bruton Smith in June 1995, which brought a date to his new Texas Motor Speedway in Fort Worth. Six months later, the Staley family sold to Bob Bahre, who added a Cup Series date for his just-opened facility in Loudon, New Hampshire.

On the day of the open house, Staley was still wearing a polo shirt with the logo of New Hampshire International Speedway — the original name that Bahre gave it, before Smith purchased it and renamed it New Hampshire Motor Speedway. Bahre kept him involved with the New England track after their business deal was reached, and several pieces of memorabilia in his office reflect that — including a trophy with his father’s face etched in the glasswork.

But Staley’s heart and his home have stayed true to Wilkes County, where he’s felt the groundswell of public support for the track’s rebirth.

“I mean, I’ve seen more enthusiasm for the revival than I’ve ever saw,” Staley says. “Everybody many years ago kind of just took it for granted that it’s always going to be here. You know, you don’t miss your water until it’s gone, I guess.”

The other side of the Staley’s office has more to see — NASCAR Rule Books from decades past, promotional posters, and a concession stand menu from the track’s last race. But there are two key pieces in the rest of the garage — his father’s Chevrolet truck, restored in gleaming red, and the pristine Pontiac Firebird pace car from North Wilkesboro Speedway’s final season, still touting the Tyson Holly Farms 400 for September 29, 1996 on its doors.

Pontiac had provided the pace cars for promotional use, and Staley said their agreement meant a new vehicle each year. When the term was up for the 1996 season, he bought it to keep.

Staley took the vehicle out for North Wilkesboro’s open house, parking it on pit road just ahead of Dale Earnhardt Jr.’s No. 3 late model. The odometer indicated just 12,775 miles on the clock. Staley chuckles when asked how many of those came five-eighths of a mile at a time.

“What they’ve done down there is just unreal, is what they’ve done, and I’m glad,” Staley says. “It’s great because gradually, people like my dad and his brother Gwyn, and maybe Benny Parsons to a certain extent, people are kind of forgetting about them. But this will bring a lot of that back and put a spotlight on some of the pioneers and the charter members and the people that really laid the foundation for NASCAR, and Dad is one of those that laid the foundation.”

The storefront

Downtown Wilkesboro — the smaller sister town to the south — has a leisurely pulse, with a historic vibe to its Main Street. But there’s an energy inside The 50’s, a diner serving homestyle breakfast and lunch with an emphasis on fast, friendly service.

Keith Johnson is quick to greet you with a smile there most days except for Wednesday, which is his golf day. His mother opened the restaurant on March 1, 1990, and he took over nearly eight years later. But one thing that didn’t come with the transfer of ownership was an explanation of why it’s called The 50’s.

“Never have figured out why she named it that,” he says, mentioning the poodle skirts that some of the wait staff wore in its early years. “She just did.”

Johnson is quick with a laugh, and his facial expression when he does shows a familiar family bloodline. He is the nephew of Junior Johnson, the original Wilkes County Wildman, famed moonshiner and an inaugural member of the NASCAR Hall of Fame. His first trip to Daytona International Speedway came as a 2-year-old, but his first memory was a visit to his uncle’s race shop.

“The first car my dad ever set me in the seat and let me crank was the ’63 with the mystery motor,” Johnson says, referring to the classic No. 3 Chevrolet Impala with 427 cubic inches of power that set the fastest qualifying lap for that year’s Daytona 500.

The walls at The 50’s are covered with framed posters and prints — many documenting the life and times of Junior Johnson, mixed with plenty others touting the University of North Carolina’s sports accomplishments. Keith Johnson was along for the ride for his uncle’s time as a team owner, and he says he still charts those years by who their driver was and what car they were fielding.

“Whatever they told me to do,” he says about his team duties. “When I should have been doing what I should have been doing, I was messing around too much. That wasn’t nobody’s fault but mine, but it was fun back then.

“I liked the days when, we wouldn’t say it was cheating. We were …,” Johnson says before pausing, trying to think of kinder words to describe his uncle’s sometimes-illegal car innovations. “We invented a lot of things,” is what he settles on.

Keith Johnson remembers playing football as a youngster in the infield at North Wilkesboro Speedway during the races, eating lunches out of car trunks. “400 laps was 400 laps,” he says. “It wasn’t until you got older that you had to work and all that other stuff.” Those memories stayed with him, even after he watched the final Cup Series race in 1996.

“It was sort of sad that you knew that was the end,” Johnson says. “You know, we understood why they were moving, but you’re really getting away from what made NASCAR. It got away from the roots and all that stuff.”

Those roots are now being replanted, and the otherwise sleepy downtown is building its anticipation. Posted on the front windows at The 50’s are fliers with a schedule of events for Thursday’s parade of NASCAR haulers through the Main Street of both ‘boros.

“I’m just glad it’s back, and I hope they do more than just the one event,” Johnson says. “I’m looking forward to them turning the lights back on.”

The builder

Ronald Queen counts himself among a fortunate group who had a regular audience with Junior Johnson. Queen worked for Johnson’s racing team from its heyday to its closing in 1995, but he remained close — growing up three miles from North Wilkesboro Speedway.

“I tell everybody the same story. Working for him, when he instilled something in you to do, when he charged you with something to do, you did it,” Queen says. “You didn’t ask questions, you didn’t understand it at the time that he charged you with the task, but you did it anyhow, and then you saw the rewards afterwards. And this has been one of the things that he guided me to.”

Queen is now the operations director of the North Wilkesboro Speedway, a role that’s kept him especially busy in the months since the All-Star Race announcement. He’s a hard-working dynamo at 63 years old, with a shock of salt-and-pepper hair and a ready gift of gab, but his efforts to restore the track pre-date any official movement toward NASCAR’s return.

His talks with Johnson intensified in 2010, when an outside promoter briefly re-opened the track for regional touring-series races. Having the track back in action was a joy, but a short-lived one. The plan was for something more sustained. Johnson’s playbook was for Queen to team up with Terri Parsons — “you’re going to have to have her,” he said — and to mobilize local officials and politicians. Lastly, Queen recalls Johnson telling him: “You’re gonna have to get that boy’s attention — ‘that boy’ being Marcus.”

“How am I going to do that?” Queen remembers saying. “He said, you’ll find a way.”

PHOTOS: Before and after at North Wilkesboro

Queen understood the power of social media, and he knew what impact a statement from Smith could hold. His word was relayed to Smith, and his assurance on the Dale Jr. Download that Wilkes County would not be forgotten soon became public. Queen can nearly recite it verbatim, two years later.

“I will say that got it to rolling a little better. The train was putting out a little more black smoke,” Queen says. “We never looked back after that.”

In August 2021 — one year before the grassroots revival races — Queen called two local fire chiefs to help spearhead a community clean-up effort at the track. He says that 150-plus volunteers showed up to assist, working for little more than a T-shirt, ballcap and a meal. Alex Key, a country music artist and Wilkesboro native, provided a free concert for those gathered. The finishing touch was a small, cloth backpack that read, “We Want You Back Track Attack.”

One of Queen’s last conversations with Johnson before his death in 2019 came as the two rode on a golf cart around his Wilkes County home, which Johnson was preparing to sell at auction. After showing Queen some of the property’s assets and what he needed doing, Johnson pulled up to a halt.

“We stopped and he took his finger and he went around a circle on the steering wheel,” Queen said. “And he said, ‘You know what I just done?’ I said, “No, Junior. I don’t have no idea. You went around that steering wheel.’ He said, ‘NASCAR is gonna have to run a full circle.’ And he said, ‘They’re gonna run that full circle. I’ll be gone, but they’ll run it, and they’re gonna come back home to roost. They’re going to want to see the roots of downhome racing and it’ll be back up there. There’s no way they can dig the roots out of the ground up there, because they’re embedded deep — since ’47. That’s what you’ve got to stand on and hold to, is because of the roots and what it means.’ ”

The moonshiner

Back in the late 1970s, wooden bleachers were added on North Wilkesboro Speedway’s backstretch, dubbed the Junior Johnson Grandstand. Enoch Staley invited a handful of close friends for a christening, like breaking a bottle of champagne across a ship’s bow. The spirits, though, had a Wilkes County connection, and a half-gallon jar of authentic moonshine did the job.

“It was probably some of my dad’s shine,” Brian Call says today from the Call Family Distillers Mash House in Wilkesboro, in between signing bottles of a big batch produced for the speedway’s reopening. Call makes the stuff legally now, but previous generations of the family produced untaxed liquor for years with deliveries made at high speed. His father, Willie Clay Call — nicknamed “The Uncatchable” and “The Bull” — was a close business associate of Johnson’s in those long-past years, and the NASCAR Hall of Famer kept him in good equipment.

“Dad would make moonshine and Junior would haul a lot of it,” Brian Call says. “Dad had hauled a bunch, but that kind of kept Junior in the racing business in the early days, and he evolved into a NASCAR owner and kind of got out of the moonshine business.

“Those guys had fast cars. One of my cousins let Dad out on the track when Fred Lorenzen was out there practicing and my dad was in one of his souped-up liquor cars Junior had fixed for him. It had a supercharger on it, and he ran Fred down and passed him out there on the track, and they pulled in the pits and Fred had to get out, go up and see what kind of motor they had in that thing. That’s pretty amazing hearing stories like that growing up.”

Brian Call lived within walking distance of the track, and those childhood years meant spending time in his aunt and uncle’s front yard watching the Cup Series haulers drive by on Speedway Road. It also meant spending restless afternoons before race weekends, watching the clock from his classroom at C.C. Wright Elementary. “My fondest memory is on a Friday when time trials were happening,” Call says, “sitting there looking out the window daydreaming waiting on my dad or somebody to pick me up so I could go watch Darrell Waltrip qualify.”

The return of racing to North Wilkesboro holds special meaning for the Call family. Zoom in close enough on the map of the track’s vicinity and the hyper-local community bears the name “Call, N.C.” Cousin Paul Call was a longtime speedway employee, serving as the track’s caretaker in the years after it closed.

“You can just see that sparkle in his eye, with racing coming back where it’s been gone for 26 years,” Brian Call says. “Businesses, what tickles me is to see everybody just filling the shelves back up in the grocery stores, and everybody just getting ready to get a little bit of the trickle effect of money coming back in.”

Call himself was doing brisk business on a Thursday afternoon before the start of the race weekend. A band played southern rock from a side stage, and customers bought memorabilia and sampled a drink called the “Raise Hell, Praise Dale” — a Wilkes County delicacy that mixes Call’s brand of whiskey with Sun Drop.

The Calls were serving cocktails more than a year ago when Marcus Smith visited the Wilkes chamber, and the family broached the idea of becoming the official moonshine for the speedway. We’ll see if we can’t make that happen, Smith said, and the deal eventually came to fruition.

The business has split time this week between its mash house operations and the race track’s new Checkered Past Speakeasy location, which is decorated with vintage memorabilia. Some of their liquor-hauling cars will be on display, with finely tuned motors that have Junior Johnson’s fingerprints under the hood. And the All-Star Race winner will receive a moonshine-themed trophy, a copper replica still that Call and his cousin, Chad Call, designed and built. “We cut the metal out by hand and soldered everything, so they’re kind of unique,” Brian Call says.

The Thursday afternoon bustle at the distillery was heightened by activity on the adjacent street. The long, straight road beside a riverside park was the staging area for the Cup Series haulers, just before their evening parade through town — an event that brought out many in the community to cheer racing’s return.

Brian Call’s childhood memories of watching those trucks roll by on Speedway Road just got a modern-day update.

“I always loved looking at the haulers as good as I do the race cars,” Call says. “It’s exciting. You know, I’m a local boy. I’ve been here my whole life and my family — my dad and grandpa — were all in the moonshine business. My grandpa and Junior’s daddy, they were in it together and make liquor together, and then their friendship went on to my dad and Junior Johnson. That passed on down. I just wish they were here to see it today.”

The neighbor

“I’m with NASCAR,” the introduction went.

“We want to say thank you,” Tina Poe replies.

“Oh, you know, I wish I could take any credit for all this,” I stammer out.

“That’s OK,” Poe says. “You can go back and tell ’em we said thank you.”

Poe is at the open house with her husband, Tim. As the two stand along pit road, she’s wearing a badge with North Wilkesboro branding that says “operations,” which speaks to how much volunteer work she’s assisted with. She also has a ballcap with the track’s logo, with the stitched-in words. “I’m Back.”

“We live at the end of the entrance,” Tina Poe says, noting their 33 years spent near the intersection of Speedway Lane and Old U.S. 421, and all the recent work that’s taken place just up the street. “It’s been kind of amazing, It’s been longed for, it’s been asked for and now all the whispers finally hit the right ears, and here we are. We had a dormant speedway, then we got a rose last year. Now we’ve got a blossoming rose bush. Welcome back to Wilkes County, where it started.”

MORE: Fans celebrate North Wilkesboro open house

Poe says volunteer work has been part of the backbone of the track’s resurgence, and her spirit of helping out goes back to the speedway’s previous life. Poe said her family helped park cars for the final seasons of racing at North Wilkesboro all the way up to 1996, and she remembers the feeling from those long-ago events well.

“You know, the fans were happy we had the race, but when you saw them leaving and they were backed up bumper to bumper by our house, I saw tears,” she says. “They knew back then, they thought that was the end, and the community thought it was over.”

It took 27 years, through the clean-up efforts, the podcast promise and the public show of support. And it became the spirit-lifter that the county needed.

“Ever since we had everything that happened last August, it’s just the morale of Wilkes County. We were all like …,” Poe says, as she slouches and hunches her shoulders to illustrate how previous years felt. “Now they’re standing up tall, their posture’s better, they’re happier people because we’ve got something. We’ve got the nostalgia that’s bringing NASCAR back.”

Poe gets more emphatic as she speaks. She’s attended community meetings about the track’s progress, and when the topic of potential objectors came up, Poe suggested any naysayers might be best advised to take vacation that week.

Talking about the “We Want You Back” campaign hits home, and she described its straightforward message as “in your face.” She remembers seeing the first billboard, then the banner on the Chamber of Commerce, and then the signs.

“It was just here, there and everywhere,” Poe says, soaking in the pit-road sun. “It was just, ‘It’s coming, it’s coming, it’s coming.’ When it started coming, you can’t keep me from being out here. Nope, nope. I’m going to be here. And I am here now.”

The community leader

Linda Cheek has been president of the Wilkes Chamber of Commerce for the last 25 years, moving back home after a brief stay in Chattanooga, where she worked in the car restoration business.

“The last two years have been the busiest of my 25 years,” she says from the shade of a new building overlooking the speedway’s fourth turn. “It really has.”

Cheek has been with the chamber long enough to remember the lean years shortly after the track had closed. The economic hit was severe. The money that NASCAR fans spent on tickets, food and lodging for two race weekends a year was significant, and the tourism supported countless jobs — not just in Wilkes County but in the surrounding area.

Count Cheek among the collaborators that Terri Parsons brought into her circle of trust. The two worked hand in hand to assemble the right people, to get local politicians aligned in working on the track and getting the message across. Everything clicked.

“First of all, I have a friend,” Cheek said of Parsons. “She’s a good friend, has been for a long time ever since she and Benny moved here and since I met her, but she’s a visionary. She’s a doer. Some people have vision, and they’re not doers. She’s one of those that has the vision and has the energy and can get things done if she believes in it and believes it’s the right thing to do. That’s what Terri does, and I’ve never seen anyone work so hard as she has for this.”

Part of that effort was collaboration on the “We Want You Back” campaign, and tourism funding was allocated toward signs and billboards bearing that message.

“I think what it did more than anything, it let the Smith family and Speedway Motorsports know that this community wanted them back, and that we were here to support every effort they did — whatever it was,” Cheek says. “We didn’t know what capacity it would be, didn’t even know if it’d be racing. We didn’t know that. We were tired of looking at this track deteriorate. … It was just letting them know that they had our support. We were here. We wanted it. We needed it.”

RELATED: Open house, final construction photos

Smith was an invited speaker in January 2022 to the annual meeting of the Wilkes Chamber of Commerce, which celebrated its own 75th anniversary that year. A capacity crowd packed into Wilkes Community College, viewing conceptual images from Speedway Motorsports that reimagined the track’s rebirth for the first time.

Smith hinted at a return to racing at a grassroots level before a full renovation, mentioning the “real possibility” of events for the Craftsman Truck Series, but also for events outside of racing as a community venue.

“When he started talking, the energy in the room could be felt,” Cheek says. “There were about 300 people in the room, and it was just different. He had notes, he laid the notes down and spoke from the heart. And I thought, big things are getting ready to happen.”

Cheek was back at the track for the grassroots revival events last August, much as she was for the evening of North Wilkesboro’s open house. It felt like home, she said. The signs around her county now say, “We Got You Back.”

“I was standing out here and I don’t know what it is. It’s just about the atmosphere,” Cheek says. “In the evenings, it really glows. Have you been here in the evenings and seen the sunset? The mountain ranges that you can see, it’s just really beautiful. But it’s just an aura about it. It’s like a fairy tale coming true.”